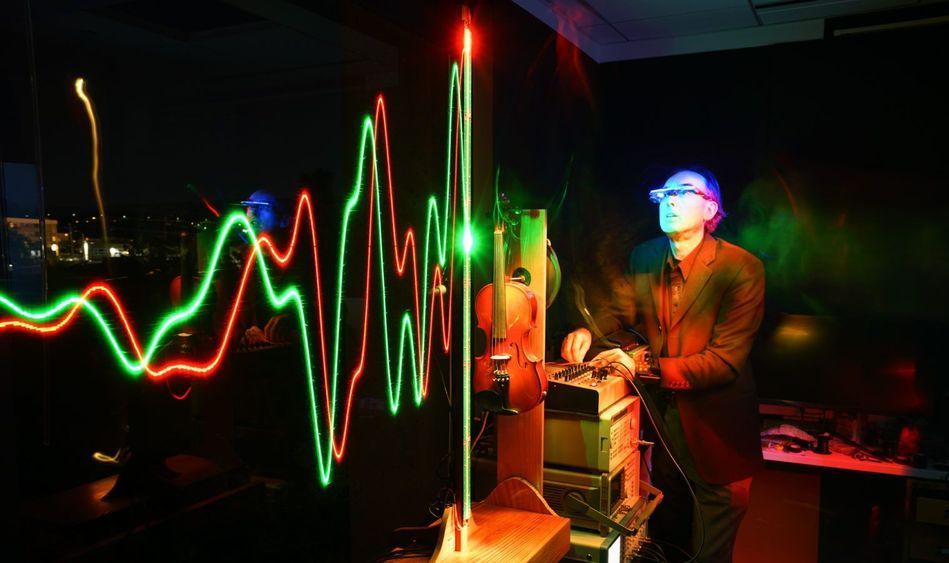

Steve Mann invented a precursor to Google Glass in the 1990s—which he now uses almost 24/7. But “the father of wearable computing” has an ominous warning about where technology is taking us next.

Category: wearables – Page 50

A professor at the University of Chicago believes he is on his way to creating a wearable for market that will manipulate your muscles with electrical impulses to cause you to move involuntarily so you can perform a physical task you otherwise didn’t know how to do, like playing a musical instrument or operating machinery.

Dr. Pedro Lopes, who heads the Human Computer Integration lab at the university, is all about integrating humans and computers, closing the gap between human and machine. His team, which focuses on engineering the next generation of wearable and haptic devices, is exploring the endless possibilities if wearables could intentionally share parts of our body for input and output, allowing computers to be more directly interwoven in our bodily senses and actuators.

Lopes’ vision: a wearable EMS device that would look like a sleeve and be able to send electrical impulses in the right timing and in the right fashion to make a user’s muscles move involuntarily to perform a physical task. EMS stands for electrical muscle stimulation.

A small clinical trial, announced by U.S. company NeuroEM Therapeutics, shows reversal of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease patients after just two months of treatment using a wearable head device. Electromagnetic waves emitted by the device appear to penetrate the brain to break up amyloid-beta and tau deposits.

The need to make some hardware systems tinier and tinier and others bigger and bigger has been driving innovations in electronics for a long time. The former can be seen in the progression from laptops to smartphones to smart watches to hearables and other “invisible” electronics. The latter defines today’s commercial data centers—megawatt-devouring monsters that fill purpose-built warehouses around the world. Interestingly, the same technology is limiting progress in both arenas, though for different reasons.

The culprit, we contend, is the printed circuit board. And the solution is to get rid of it.

Our research shows that the printed circuit board could be replaced with the same material that makes up the chips that are attached to it, namely silicon. Such a move would lead to smaller, lighter-weight systems for wearables and other size-constrained gadgets, and also to incredibly powerful high-performance computers that would pack dozens of servers’ worth of computing capability onto a dinner-plate-size wafer of silicon.

Combining new classes of nanomembrane electrodes with flexible electronics and a deep learning algorithm could help disabled people wirelessly control an electric wheelchair, interact with a computer or operate a small robotic vehicle without donning a bulky hair-electrode cap or contending with wires.

By providing a fully portable, wireless brain-machine interface (BMI), the wearable system could offer an improvement over conventional electroencephalography (EEG) for measuring signals from visually evoked potentials in the human brain. The system’s ability to measure EEG signals for BMI has been evaluated with six human subjects, but has not been studied with disabled individuals.

The project, conducted by researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology, University of Kent and Wichita State University, was reported on September 11 in the journal Nature Machine Intelligence.

New technological devices are prioritizing non-invasive tracking of vital signs, not only for fitness monitoring, but also for the prevention of common health problems such as heart failure, hypertension and stress-related complications, among others. Wearables based on optical detection mechanisms are proving an invaluable approach for reporting on our bodies inner workings and have experienced a large penetration into the consumer market in recent years. Current wearable technologies, based on non-flexible components, do not deliver the desired accuracy and can only monitor a limited number of vital signs. To tackle this problem, conformable non-invasive optical-based sensors that can measure a broader set of vital signs are at the top of the end-users’ wish list.

In a recent study published in Science Advances, ICFO researchers have demonstrated a new class of flexible and transparent wearable devices that are conformable to the skin and can provide continuous and accurate measurements of multiple human vital signs. These devices can measure heart rate, respiration rate and blood pulse oxygenation, as well as exposure to UV radiation from the sun. While the device measures the different parameters, the read-out is visualized and stored on a mobile phone interface connected to the wearable via Bluetooth. In addition, the device can operate battery-free since it is charged wirelessly through the phone.

“It was very important for us to demonstrate the wide range of potential applications for our advanced light sensing technology through the creation of various prototypes, including the flexible and transparent bracelet, the health patch integrated on a mobile phone and the UV monitoring patch for sun exposure. They have shown to be versatile and efficient due to these unique features,” reports Dr. Emre Ozan Polat, first author of this publication.

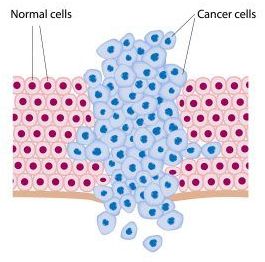

Biopsies are currently the best way to detect cancer, but they’re invasive, uncomfortable, and can take a while to come back. Researchers have long been trying to find ways to eliminate the need for biopsies, and a team from the University of Michigan may have found one. Their new device, which is currently being tested, may be able to detect cancer cells that are circulating in a patient’s blood.

The University of Michigan team calls their new device “the epitome of precision medicine.” Dr. Daniel Hayes, Professor of Breast Cancer Research at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer center, believes that getting cancer cells from a patient’s blood could help researchers to learn more about the makeup of the tumor. He and his team created a wearable device that looks through the blood to filter out cancerous cells. If the device is found to be successful, it may eventually replace liquid biopsies (blood or urine samples) that pick up cancer markers.

Malignant tumors release cells into a patient’s blood, meaning that researchers could detect the presence of cancer through a blood sample. The problem is that the cancerous cells enter the bloodstream and circulate so quickly that they may not appear in one single blood sample. This issue is what sparked Dr. Hayes and his team to develop a device that actually searches for the cancerous cells.

Malignant tumors release cells into a patient’s blood, meaning that researchers could detect the presence of cancer through a blood sample. The problem is that the cancerous cells enter the bloodstream and circulate so quickly that they may not appear in one single blood sample. This issue is what sparked Dr. Hayes and his team to develop a device that actually searches for the cancerous cells.

In what could be a breakthrough for body sensor and navigation technologies, researchers at KTH have developed the smallest accelerometer yet reported, using the highly conductive nanomaterial, graphene.

Each passing day, nanotechnology and the potential for graphene material make new progress. The latest step forward is a tiny accelerometer made with graphene by an international research team involving KTH Royal Institute of Technology, RWTH Aachen University and Research Institute AMO GmbH, Aachen.

Among the conceivable applications are monitoring systems for cardiovascular diseases and ultra-sensitive wearable and portable motion-capture technologies.

Researchers at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology have recently developed a flexible and imperceptible magnetic skin that adds permanent magnetic properties to all surfaces to which it is applied. This artificial skin, presented in a paper published in Wiley’s Advanced Materials Technologies journal, could have numerous interesting applications. For instance, it could enable the development of more effective tools to aid people with disabilities, help biomedical professionals to monitor their patients’ vital signs, and pave the way for new consumer tech.

“Artificial skins are all about extending our senses or abilities,” Adbullah Almansouri, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told TechXplore. “A great challenge in their development, however, is that they should be imperceptible and comfortable to wear. This is very difficult to achieve reliably and durably, if we need stretchable electronics, batteries, substrates, antennas, sensors, wires, etc. We decided to remove all these delicate components from the skin itself and place them in a comfortable nearby location (i.e., inside of eye glasses or hidden in a fabric).”

The artificial skin, developed under the supervision of Prof. Jürgen Kosel, is magnetic, thin and highly flexible. When it is worn by a human user, it can be easily tracked by a nearby magnetic sensor. For instance, if a user wears it on his eyelid, it allows for his eye movements to be tracked; if worn on fingers, it can help to monitor a person’s physiological responses or even to control switches without touching them.

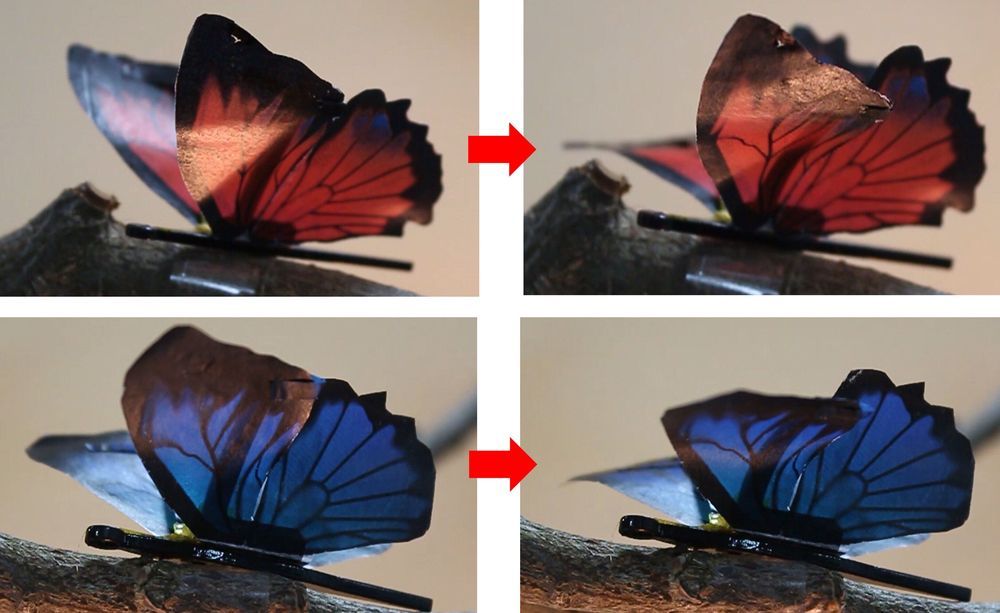

Wearing a flower brooch that blooms before your eyes sounds like magic. KAIST researchers have made it real with robotic muscles.

Researchers have developed an ultrathin, artificial muscle for soft robotics. The advancement, recently reported in the journal Science Robotics, was demonstrated with a robotic blooming flower brooch, dancing robotic butterflies and fluttering tree leaves on a kinetic art piece.

The robotic equivalent of a muscle that can move is called an actuator. The actuator expands, contracts or rotates like muscle fibers using a stimulus such as electricity. Engineers around the world are striving to develop more dynamic actuators that respond quickly, can bend without breaking, and are very durable. Soft, robotic muscles could have a wide variety of applications, from wearable electronics to advanced prosthetics.