Identified as the most complete Australopithecus fossil discovered to date, “Little Foot” was buried in sediments whose movement and weight caused fractures and deformations, making analysis of its skull—and more particularly its face—difficult. This anatomical region, which is essential for understanding the adaptations of our ancestors and relatives to their environment, has now been virtually reconstructed for the first time by a CNRS researcher and her British and South African colleagues. These are published in Comptes Rendus Palevol.

A comparative analysis of this reconstruction with several extant great apes and three other Australopithecus specimens reveals that the face of “Little Foot” is closer in terms of size and morphology to Australopithecus specimens from eastern Africa than to those from southern Africa. This finding raises questions about the relationships between these different populations and about the chronology of the evolutionary processes that reshaped the faces of these hominins, particularly the orbital region, which appears to have been subject to strong selective pressures.

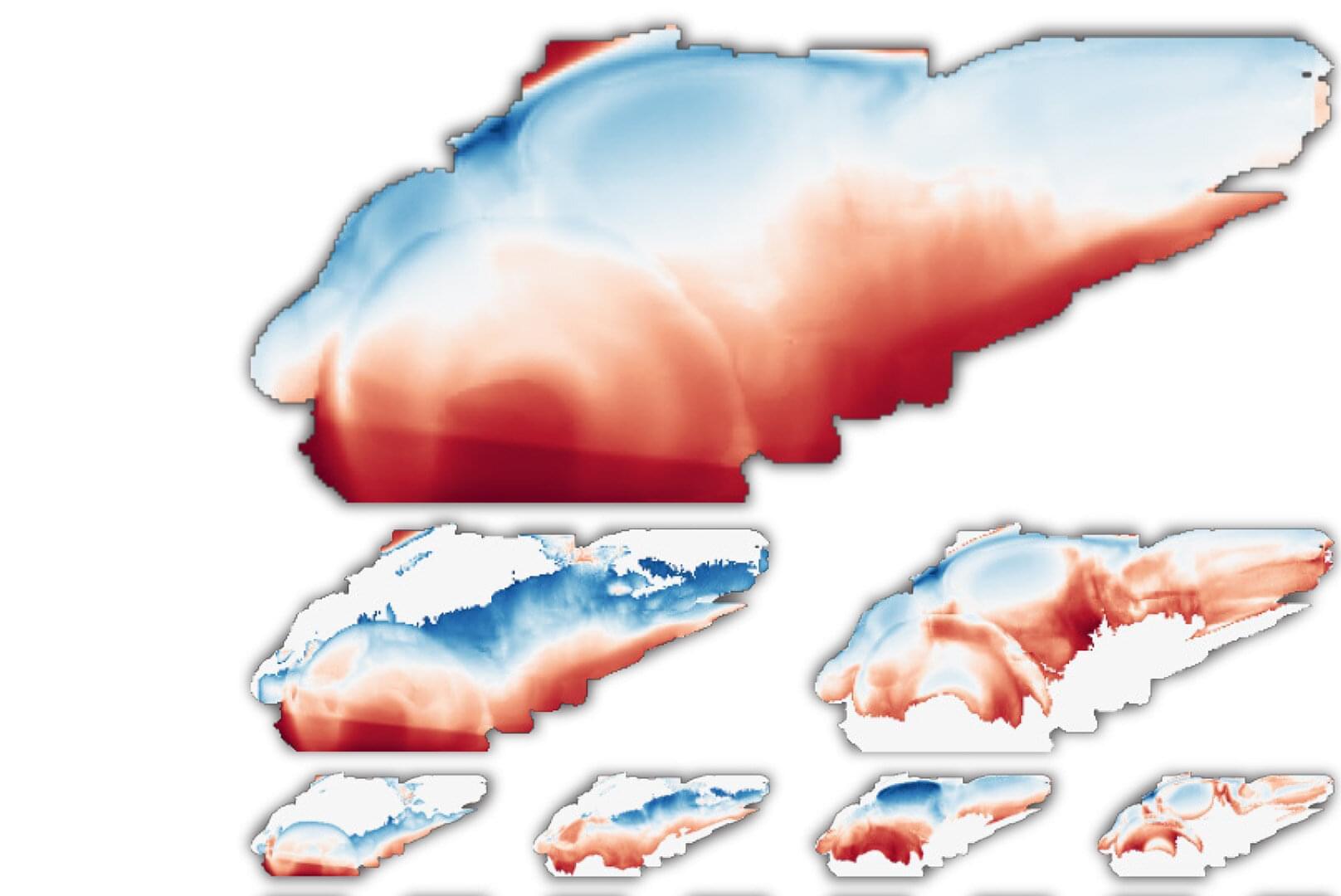

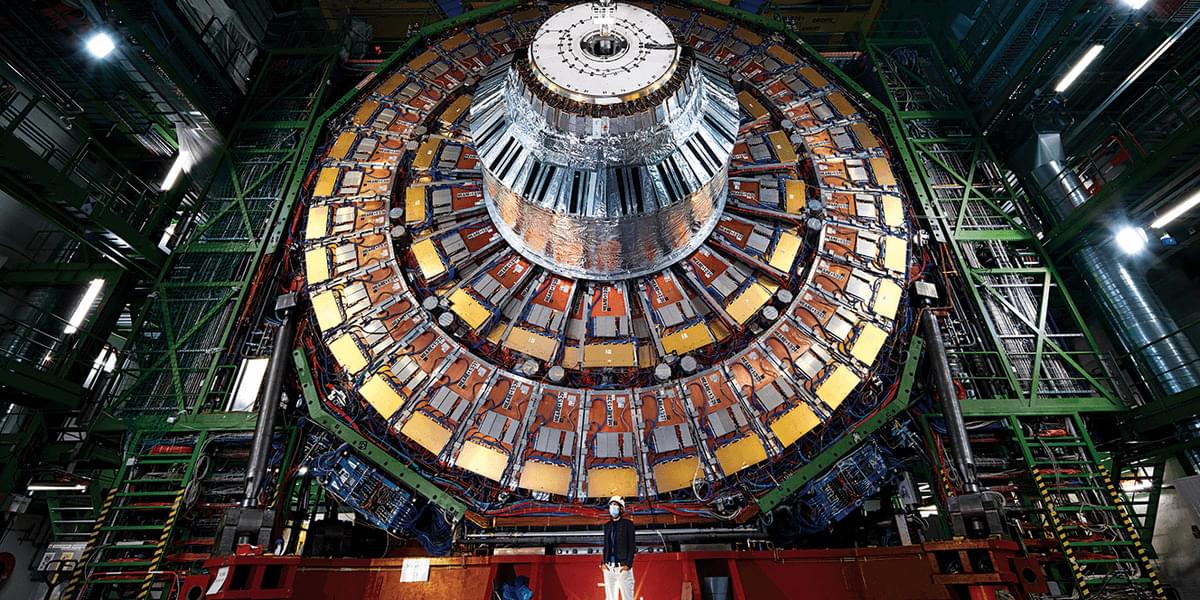

The skull was first transported to the Diamond Light Source synchrotron (United Kingdom), where it was carefully digitized. The research team then virtually isolated the bone fragments using semi-automated methods and supercomputers. Their realignment resulted in a 3D reconstruction with a resolution of 21 microns. More than five years were required to complete this reconstruction.