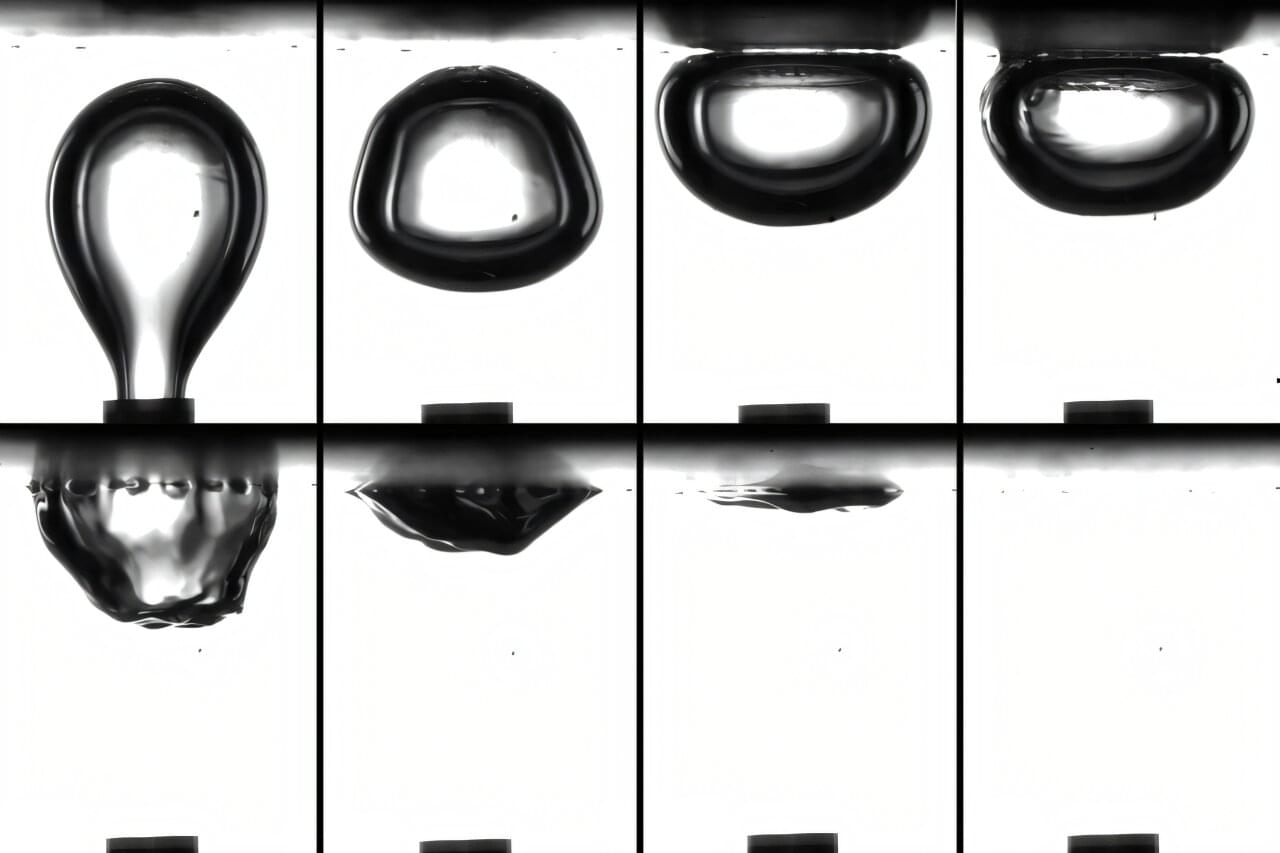

A new experiment has uncovered the mechanism responsible for the screeching sound made by peeling sticky tape. Using a combination of ultrafast imaging and synchronized acoustic recordings, Sigurdur Thoroddsen and colleagues at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology have shown that the noise is produced by a rapid train of tiny shockwaves, released through a specialized form of stick–slip motion. The research is published in Physical Review E.

If you’ve ever used sticky tape, you’ll probably be all too familiar with the harsh sound it makes as it peels away from a surface. Yet despite decades of experimental scrutiny, physicists have yet to fully explain the origins of this intriguing acoustic effect.

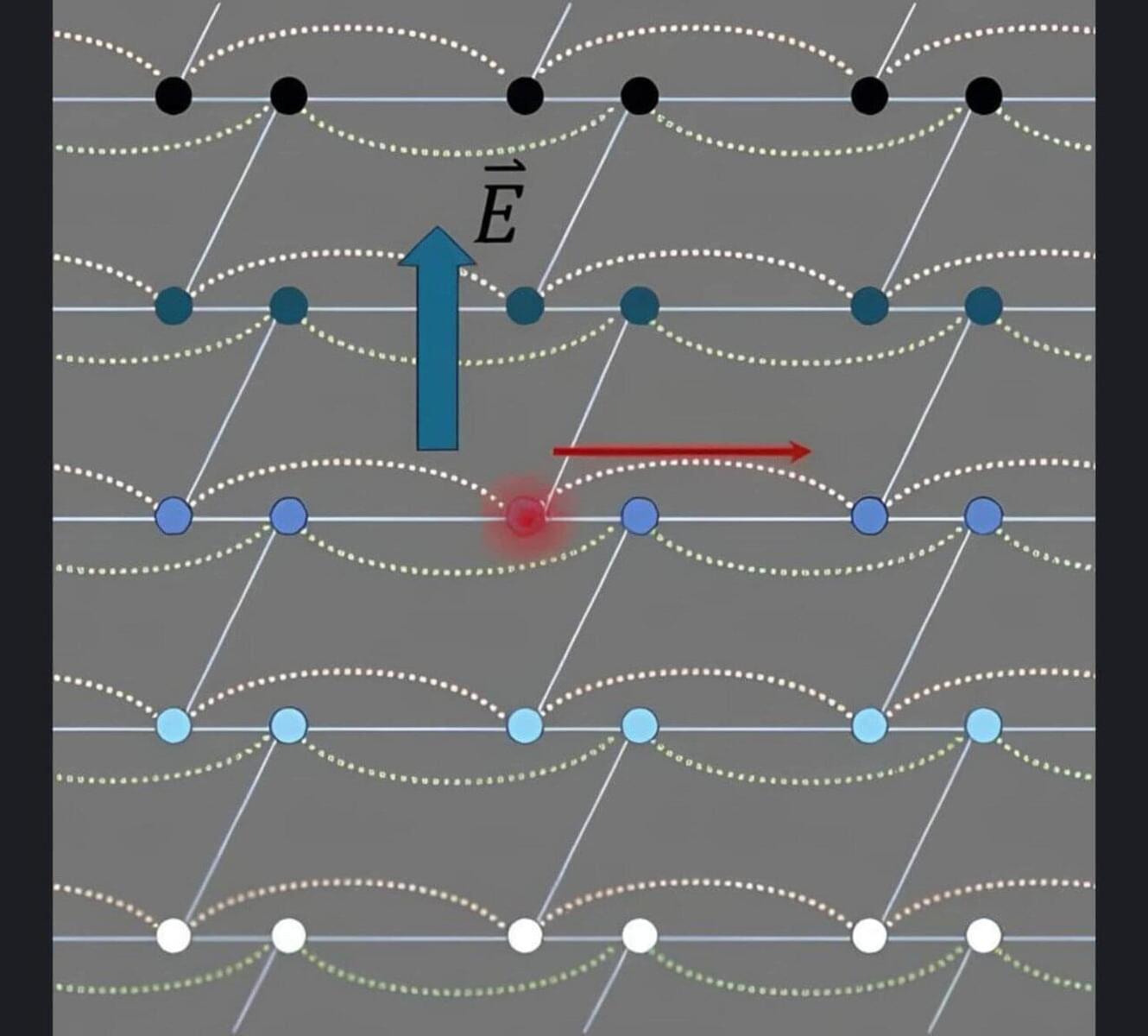

Previous studies established that peeling proceeds via a “stick–slip” mechanism—a jerky motion characterized by brief, rapid accelerations interrupted by sudden stops. Similar dynamics underpin phenomena ranging from earthquakes to the squeak of basketball shoes on a polished wooden court. However, the fine details of how this process unfolds in peeling tape turned out to be more complex than they first appeared.