Ted Brown has been involved in cryonics since the 1960s.

Category: life extension

The 5 Foods Every 100-Year-Old Ate Daily (Blue Zones Diet Breakdown)

The controversial diet truth backed by 155 dietary surveys across 90 years that food scientists don’t want you to know.

Dan Buettner exposes why meta-analyses prove most nutritional debates wrong and reveals what centenarians actually ate as children to live past 100.

The peasant food formula that’s cheaper than a hamburger, 50 times more nutrient dense, and leaves you completely satisfied.

Plus why the 15 countries with the highest life expectancy all eat white rice daily.

Dan Buettner is a New York Times bestselling author, National Geographic Fellow, and co-producer of the Emmy Award winning Netflix series Live to 100: Secrets of the Blue Zones.

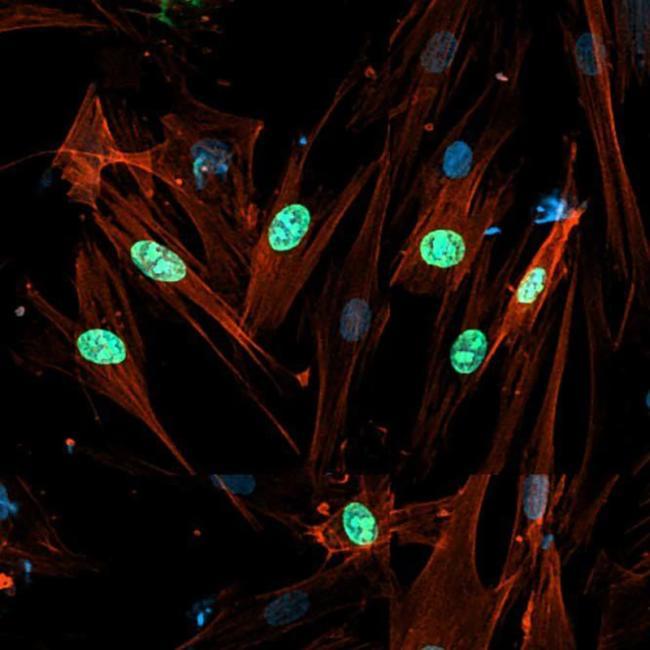

Mechanisms and Regulation of Cellular Senescence

Cellular senescence is generally an irreversible proliferative arrest in damaged normal cells that have exited the cell cycle. These cells display high metabolic activities [1], remain viable, and actively suppress apoptosis [2, 3]. Senescent cells present unique morphological and molecular characteristics and functions that distinguish them from other nondividing cell populations, such as quiescent cells and terminally differentiated cells [4, 5, 6]. The hallmarks of cellular senescence include: prolonged cell cycle arrest, transcriptional changes, acquisition of a bioactive secretome, known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), macromolecular damage, and deregulated metabolism [7].

Replicative senescence was the first cellular senescence subtype to be described [8]. It is induced after serial propagation of normal human cells in culture and is caused by telomere erosion and the consequent increase in DNA lesions [9, 10,11,12]. The limited lifespan of most (perhaps all) cultured primary cells is influenced by the species and tissue type from which they were derived. Senescence can also be triggered by many other intrinsic and extrinsic factors, particularly, replicative stress, oxidative damage, metabolism dysfunctions, cytokines, oncogene activation, and chemotherapy agents. All these factors can induce DNA damage and senescence in normal and cancer cells (in some contexts) [6]. Cellular senescence occurs not only in vitro (i.e., cell culture models), but also in various tissues in vivo [13,14,15,16].

Senescence is an important contributor to cancer and aging, two processes characterized by a time-dependent accumulation of cell damage and dysfunction. Senescence markers are detected in premalignant tumor lesions but not at later stages of tumor development [17,18,19]. The proliferative arrest imposed by cellular senescence represents an early barrier against cancer initiation by preventing the propagation of damaged DNA to the next generation of cells [18,20]. Therefore, it has been proposed that senescence escape is required for tumor progression to overt malignancy [18,21]. On the other hand, senescent fibroblasts can influence their local environment by turning into proinflammatory cells that can promote the growth of transformed or preneoplastic neighboring epithelial cells in culture and in vivo [22,23,24].

Funding for Cryostasis

Affordable Options Cryopreservation is far more affordable than you might think. There are many ways to fund your cryopreservation. MEMBERSHIP FEES MEMBERSHIP INITIATION HUMAN CRYOPRESERVATION LIFETIME $1,250 once none $28,000 once YEARLY $120 per year $200 once $35,000 once (Human cryopreservation prices do not include “Local Help” cost for a […]

Scientists reverse muscle aging in mice and discover a surprising catch

A UCLA study in mice reveals that aging muscle stem cells accumulate a protein that slows repair but boosts survival. This protein, NDRG1, acts like a brake, preventing cells from activating quickly after injury. When researchers blocked it in older mice, muscle healing sped up dramatically — but stem cells became less resilient over time. The work suggests aging may reflect a survival trade-off rather than straightforward decline.

Common anti-seizure drug prevents Alzheimer’s plaques from forming

At the heart of the new discovery is amyloid precursor protein (APP), a protein that plays important roles in brain development and synaptic formation. Abnormal processing of APP can lead to the production of amyloid‑beta peptides, which play a central role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The scientists found that how APP is trafficked also controls whether a neuron forms amyloid-beta 42.

During the synaptic vesicle cycle — a fundamental process that underlies every thought, movement, memory or sensation — levetiracetam binds to a protein called SV2A. This interaction slows down a step in which neurons recycle synaptic vesicle components from the cell’s surface. By pausing this recycling process, the drug enables APP to remain on the cell’s surface longer, diverting it away from the pathway that produces toxic amyloid‑beta 42 proteins.

“In our 30s, 40s and 50s, our brains are generally able to steer proteins away from harmful pathways,” the author said. “As we age, that protective ability gradually weakens. This is not a statement of disease; this is just a part of aging. But in brains developing Alzheimer’s, too many neurons go astray, and that’s when you get amyloid-beta 42 production. And then it’s tau (or ‘tangles’), and then it’s dead cells, then dementia, then neuroinflammation — and then it’s too late.”

To effectively prevent Alzheimer’s symptoms, high-risk individuals would need to begin taking levetiracetam “very, very early,” the author said, possibly up to 20 years before the new FDA-approved Alzheimer’s disease test would even capture mildly elevated levels of amyloid-beta 42.

“You couldn’t take this when you already have dementia because the brain has already undergone a number of irreversible changes and a lot of cell death,” the author said.

Leveraging its status as an FDA-approved and widely used drug, the team mined existing human clinical data to investigate whether Alzheimer’s patients who took levetiracetam experienced slowed cognitive decline. They obtained clinical data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center and conducted a correlative analysis, finding that Alzheimer’s patients who took levetiracetam were associated with a significant delay from the diagnosis of cognitive decline to death compared to those taking lorazepam or no/other anti-epileptic drugs. ScienceMission sciencenewshighlights.

Cryosphere Chat — Tomorrow Bio’s Big Announcement, Biostasis Summit Updates

In this epsiode of the Cryosphere Chat we discuss:

● The themes of this year’s Biostasis Summit.

● Our thoughts on Tomorrw Bio’s big announcement about longevity experts.

● Greg Fahy’s paper on ultrastructure preservation in vitrified brains.

Links:

Buy tickets for the Biostasis days at Vitalist Bay: https://vitalistbay.com/ (use code CRYOSPHERE20 for 20% off)

Biostasis Summit needs based discount application: https://forms.gle/4pR3r4uvXprc4mH99

Biostasis Summit pitch application: https://forms.gle/FQsqx9thLvryKteq8

Join the Biostasis Summit mailing list: https://www.globalcryonicssummit.com/

Survey of cryonicists: https://cryospherepress.substack.com/p/the-cryonics-survey-of-2022-part.

Cryonics Subreddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/cryonics/

Cryosphere Discord: https://discord.gg/ndshSfQwqz.

Cryosphere Substack: https://cryospherepress.substack.com/