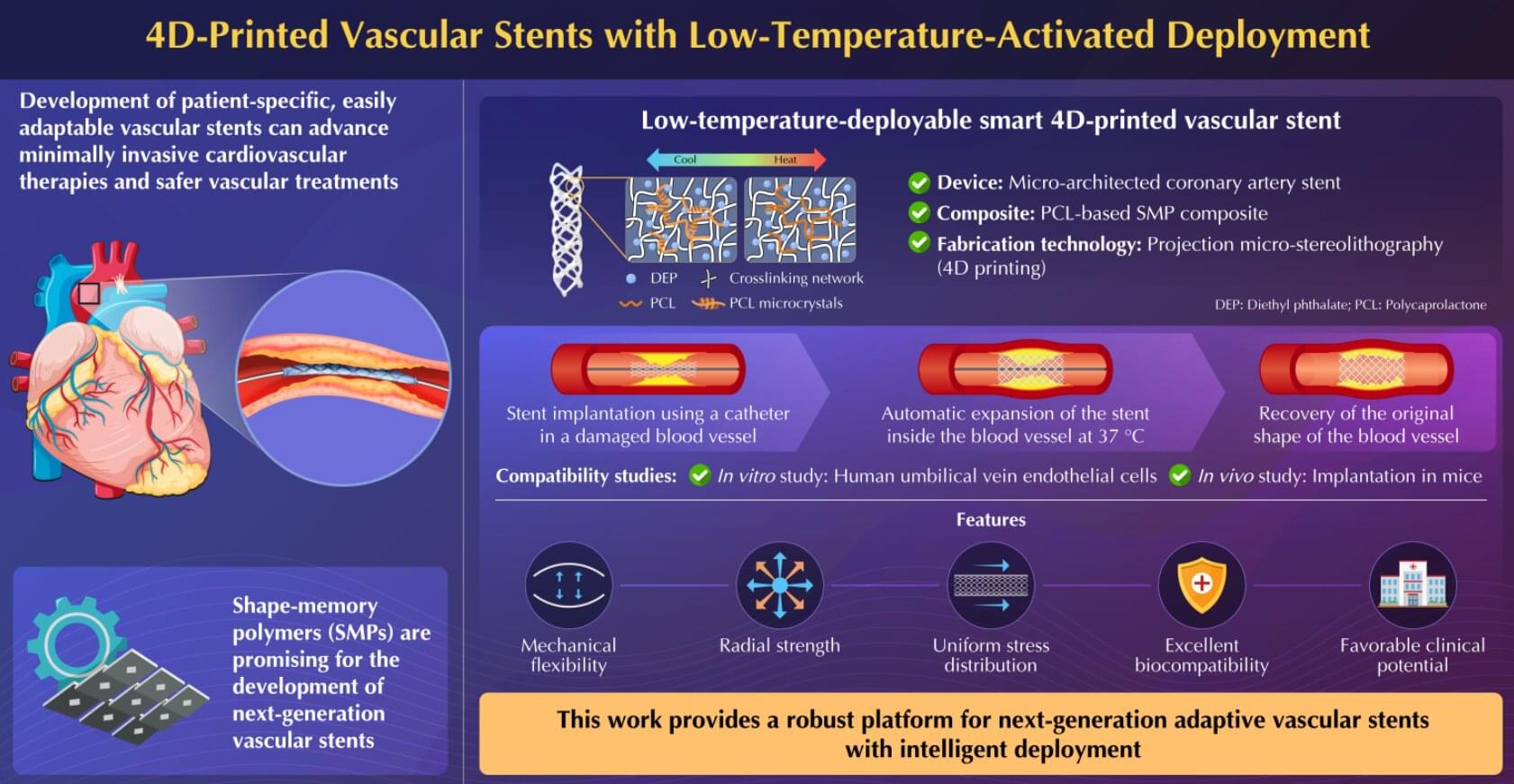

Next-generation vascular stents can make cardiovascular therapies minimally invasive and vascular treatments safe and less burdensome. In a new advancement, researchers from Japan and China have successfully proposed a novel adaptive 4D-printed vascular stent based on shape-memory polymer composite. The stent exhibits mechanical flexibility, radial strength, biomechanical compliance, and cytocompatibility in in vitro and in vivo experiments, making them promising for future clinical applications.

Cardiovascular diseases constitute a major global health concern. Various complications that affect normal blood flow in arteries and veins, such as stroke, blood clot formation in veins, blood vessel rupture, and coronary artery disease, often require vascular treatments. However, existing vascular stent devices often require complex, invasive deployment procedures, making it necessary to explore novel materials and manufacturing technologies that could enable such medical devices to work more naturally with the human body.

Moreover, the development of patient-specific, adaptively deployable vascular stents is crucial to further advance minimally invasive cardiovascular therapies and make vascular treatments safe and less burdensome for both patients and health care providers.