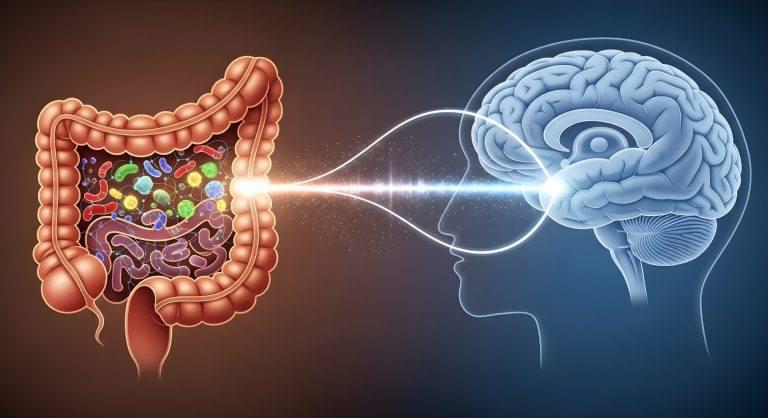

The sight of a delectable plate of lasagna or the aroma of a holiday ham are sure to get hungry bellies rumbling in anticipation of a feast to come. But although we’ve all experienced the sensation of “eating” with our eyes and noses before food meets mouth, much less is known about the information superhighway, known as the vagus nerve, that sends signals in the opposite direction — from your gut straight to your brain.

These signals relay more than just what you’ve eaten and when you are full. A new study in mice from researchers at Stanford Medicine and the Palo Alto, California-based Arc Institute has identified a critical link between the bacteria that live in your gut and the cognitive decline that often occurs with aging.

“Although memory loss is common with age, it affects people differently and at different ages,” said Christoph Thaiss, PhD, assistant professor of pathology. “We wanted to understand why some very old people remain cognitively sharp while other people see significant declines beginning in their 50s or 60s. What we learned is that the timeline of memory decline is not hardwired; it’s actively modulated in the body, and the gastrointestinal tract is a critical regulator of this process.”

Aging causes changes in gut bacteria in mice, which hampers communication between the intestines and the brain. Restoring this connection helped old mice form memories as well as young animals.