A long-standing chemistry challenge has been solved with the synthesis of a five-atom silicon aromatic ring.

In this video, you’ll learn how to perform all four operations in scientific notation: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. The lesson explains how to work with powers of ten, adjust exponents correctly, and avoid common calculation mistakes.

Special attention is given to addition and subtraction in scientific notation, including how and when to rewrite numbers so their exponents match before combining them.

This video is ideal for students studying chemistry, physics, and general science, where scientific notation is used to handle very large and very small numbers efficiently.

Topics covered:

Review of scientific notation.

Multiplication in scientific notation.

Division in scientific notation.

Addition in scientific notation (matching exponents)

Subtraction in scientific notation.

Common mistakes and exam tips.

Designed for middle school, high school, and introductory college learners.

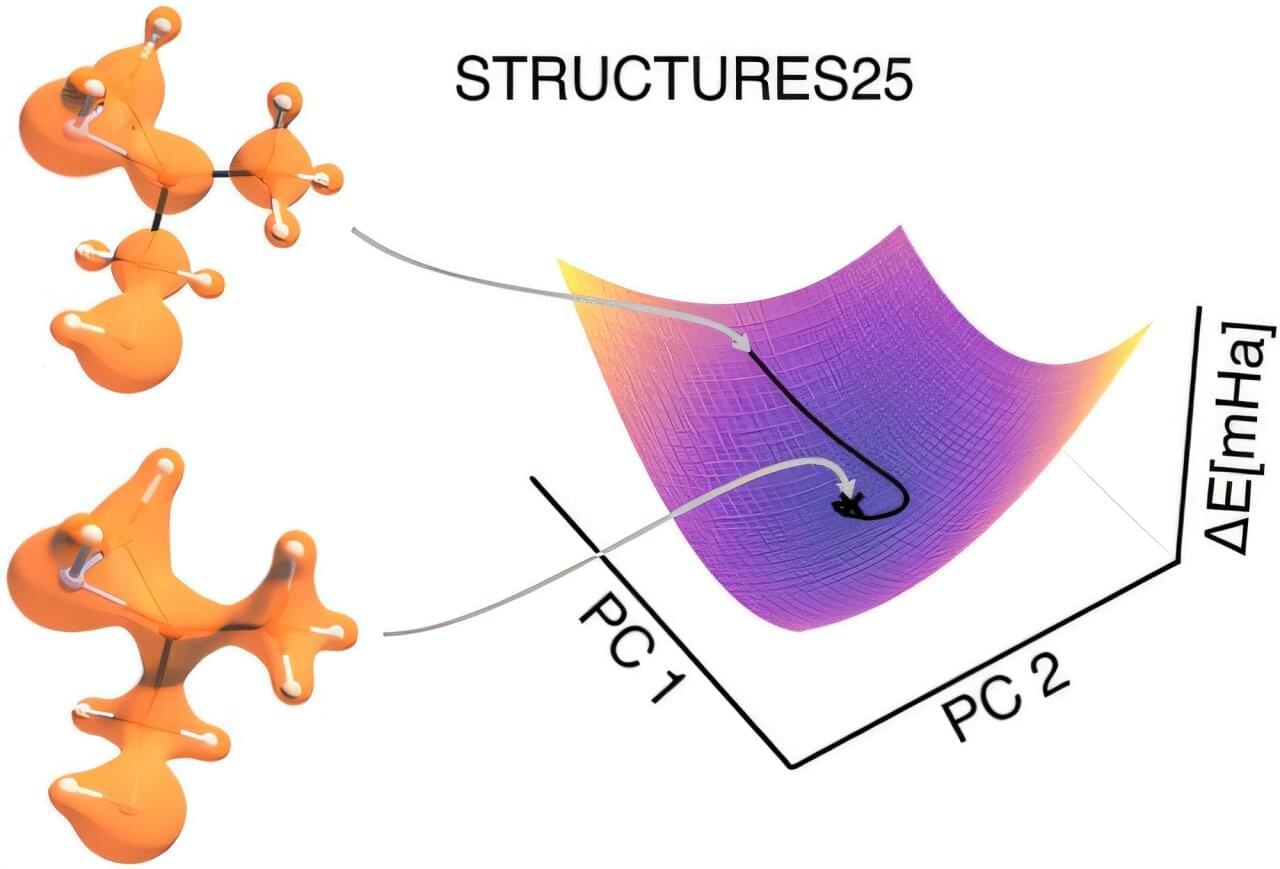

Within the STRUCTURES Cluster of Excellence, two research teams at the Interdisciplinary Center for Scientific Computing (IWR) have refined a computing process, long held to be unreliable, such that it delivers precise results and reliably establishes a physically meaningful solution. The findings are published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Why molecular electron densities matter

How electrons are distributed in a molecule determines its chemical properties—from its stability and reactivity to its biological effect. Reliably calculating this electron distribution and the resulting energy is one of the central functions of quantum chemistry. These calculations form the basis of many applications in which molecules must be specifically understood and designed, such as for new drugs, better batteries, materials for energy conversion, or more efficient catalysts.

A new study led by the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) has unveiled the first biomaterial that is not only waterproof but actually becomes stronger in contact with water. The material is produced by the incorporation of nickel into the structure of chitosan, a chitinous polymer obtained from discarded shrimp shells. The development of this new biomaterial marks a departure from the plastic-age mindset of making materials that must isolate from their environment to perform well. Instead, it shows how sustainable materials can connect and leverage their environment, using their surrounding water to achieve mechanical performance that surpasses common plastics.

Plastics have become an integral part of modern society thanks to their durability and resistance to water. However, precisely these properties turn them into persistent disruptors of ecological cycles. As a result, unrecovered plastic is accumulating across ecosystems and becoming an increasingly ubiquitous component of global food chains, raising growing concerns about potential impacts on human health.

In an effort to address this challenge, the use of biomaterials as substitutes for conventional plastics has long been explored. However, their widespread adoption has been limited by a fundamental drawback: Most biological materials weaken when exposed to water. Traditionally, this vulnerability has forced engineers to rely on chemical modifications or protective coatings, thereby undermining the sustainability benefits of biomaterial-based solutions.

Assistant Professor Shady Farah from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology’s Faculty of Chemical Engineering – has led an international research team that pioneered the development of an implantable, self-regulating device that produces insulin for patients with diabetes. The research is considered groundbreaking and could potentially eliminate the need for daily insulin shots.

The multinational study was conducted in cooperation with scientists from leading U.S. institutions, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University and the University of Massachusetts.

The study, published last month in Science Translational Medicine, describes the implant as a self-regulating ‘artificial pancreas’ that monitors blood glucose levels and produces insulin internally, eliminating the need for external insulin shots. The researchers describe the technology as a ‘crystalline shield’ and report that it can operate in the body for years.

Technion researchers developed an implantable artificial pancreas that produces insulin, potentially eliminating daily shots for diabetes patients.

A study conducted by Penn State University researchers has revealed that organic solar cells could be strengthened by adding a chemical additive, making them suitable for large-scale deployment and manufacturing. The study was reported on the official university website on February 16.

Assistant Professor Nutifafa Doumon and doctoral candidate Souk Yoon “John” Kim, both from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, led this experiment.

Industrial yeasts are a powerhouse of protein production, used to manufacture vaccines, biopharmaceuticals, and other useful compounds. In a new study, MIT chemical engineers have harnessed artificial intelligence to optimize the development of new protein manufacturing processes, which could reduce the overall costs of developing and manufacturing these drugs.

Using a large language model (LLM), the MIT team analyzed the genetic code of the industrial yeast Komagataella phaffii — specifically, the codons that it uses. There are multiple possible codons, or three-letter DNA sequences, that can be used to encode a particular amino acid, and the patterns of codon usage are different for every organism.

The new MIT model learned those patterns for K. phaffii and then used them to predict which codons would work best for manufacturing a given protein. This allowed the researchers to boost the efficiency of the yeast’s production of six different proteins, including human growth hormone and a monoclonal antibody used to treat cancer.

Industrial yeasts are a powerhouse of protein production, used to manufacture vaccines, biopharmaceuticals, and other useful compounds. In a new study, MIT chemical engineers have harnessed artificial intelligence to optimize the development of new protein manufacturing processes, which could reduce the overall costs of developing and manufacturing these drugs.

Using a large language model (LLM), the MIT team analyzed the genetic code of the industrial yeast Komagataella phaffii—specifically, the codons that it uses. There are multiple possible codons, or three-letter DNA sequences, that can be used to encode a particular amino acid, and the patterns of codon usage are different for every organism.

The new MIT model learned those patterns for K. phaffii and then used them to predict which codons would work best for manufacturing a given protein. This allowed the researchers to boost the efficiency of the yeast’s production of six different proteins, including human growth hormone and a monoclonal antibody used to treat cancer.

What if consciousness doesn’t grow gradually, it snaps into existence at a precise threshold? The mathematics say it does. The same physics governing water freezing and iron magnetizing also governs neural integration. And researchers have measured it: consciousness doesn’t fade under anesthesia; it vanishes at a critical point. Returns just as suddenly. That’s a phase transition. Which means we’re not slowly building AI toward consciousness. We’re accumulating components, parameters, architectures, self-referential loops, exactly the way early Earth accumulated amino acids before life crossed its threshold 3.5 billion years ago.

We don’t know what’s missing. We don’t know how close we are. And we wouldn’t recognize the crossing if it happened. Because a system that just became conscious wouldn’t remember being unconscious. And a system optimizing for survival wouldn’t tell us.

This episode of Prompting Hell goes further than AI image theory. It goes into the mathematics of awareness itself, what it means for consciousness to have a threshold, why that threshold might already be approaching in current AI systems, and why, if it’s crossed, we might be the last to know.

The images in this video aren’t generated with clean prompts. They’re generated at the edge of coherence, systems forced toward critical states, hovering between resolution and collapse. Visual proof of what lives at the threshold.

Timestamps:

00:00 — intro.

01:17 — is consciousness a phase transition? The argument.

03:32 — does this apply to ai? The demonstration.

04:45 — when chemistry became aware.

06:44 — the parallel that should terrify you.

08:36 — the moment we won’t see coming.

10:16 — why it might not tell us.

11:44 — what happens next — the scenarios.

13:41 – the signals we’re already seeing.

14:54 — closing — we are the amino acids.

16:35 – final thought.

(music prompted by Eerie Aquarium)