For the first time, researchers in China have accurately quantified how chaos increases in a quantum many-body system as it evolves over time. Combining experiments and theory, a team led by Yu-Chen Li at the University of Science and Technology of China showed that the level of chaos grows exponentially when time reversal is applied to these systems—matching predictions of their extreme sensitivity to errors. The research has been published in Physical Review Letters.

The butterfly effect is a well-known expression of chaos theory. It describes how a complex system can quickly become unpredictable as it evolves: make just a few small errors when specifying the system’s starting conditions, and it may look completely different from your calculations a short time later.

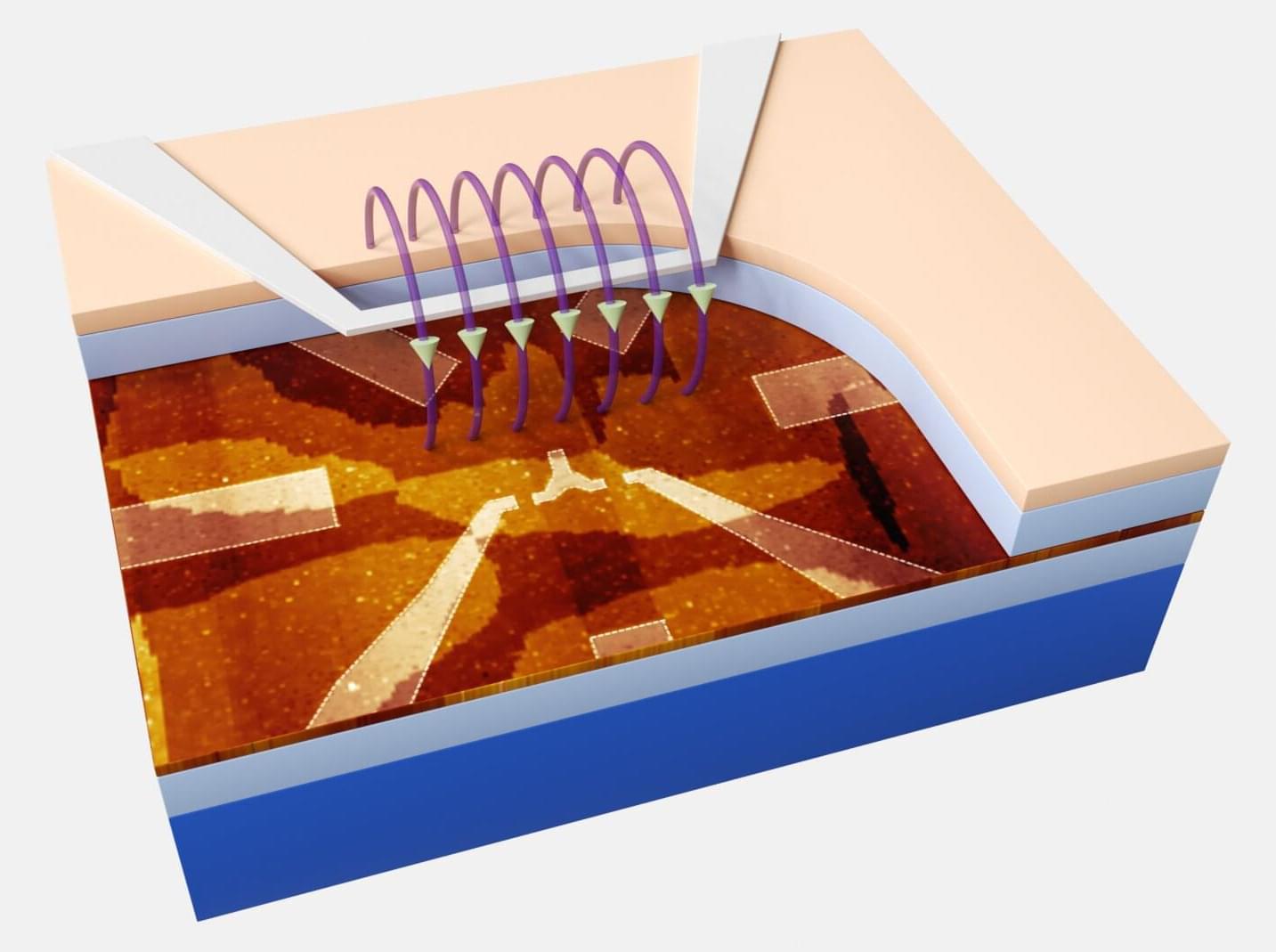

This effect is especially relevant in many-body quantum systems, where entanglement creates intricate webs of interconnection between particles—even in relatively small systems. As the system evolves, information about its initial state becomes increasingly dispersed across these connections.