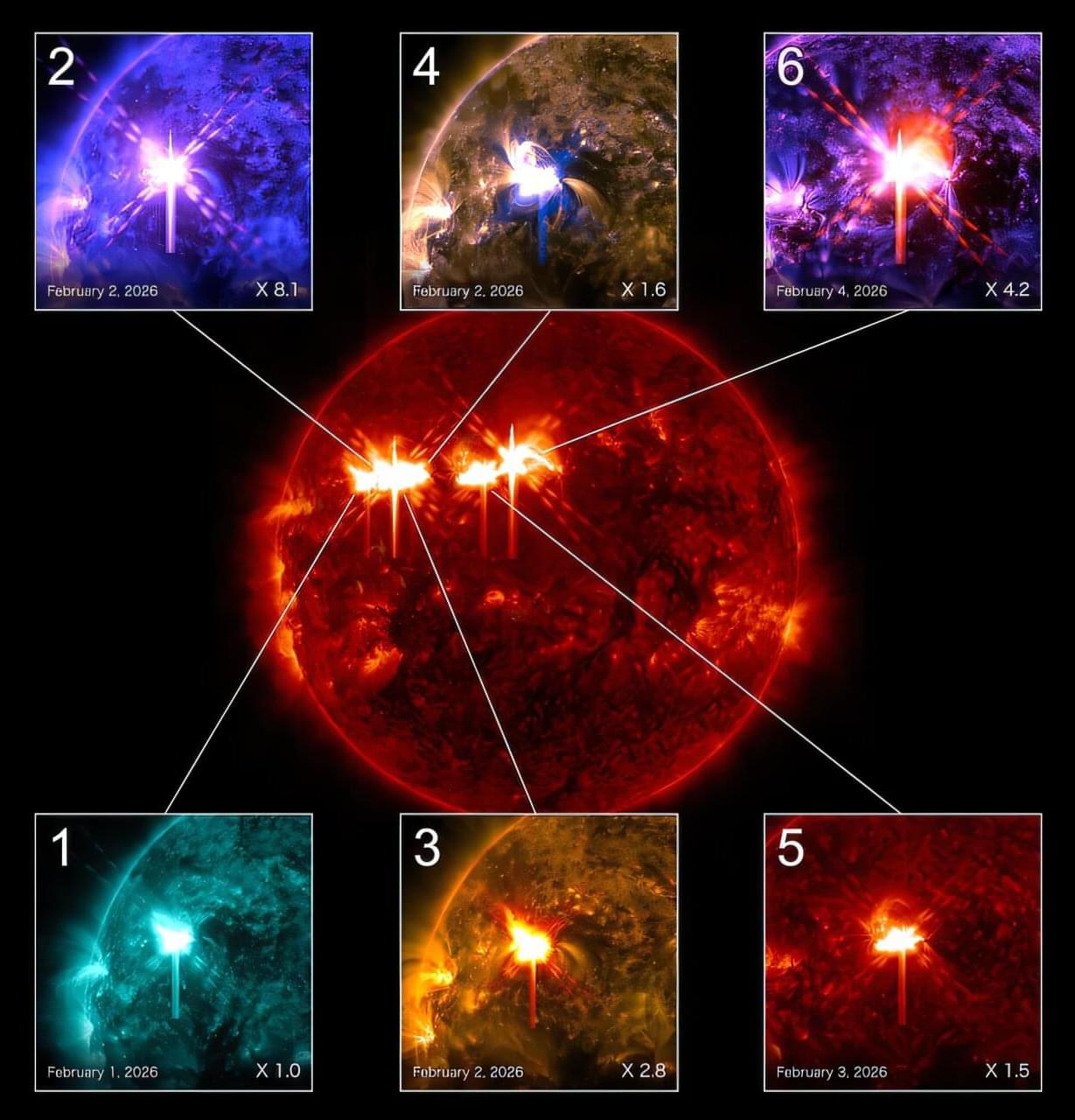

On July 2, 2025, space telescopes monitoring the sky for brief, one-and-done flashes of high-energy light saw something that nobody expected: a gamma-ray burst (GRB) that came back again and again, stretching what is usually a single “burst” lasting seconds to minutes into an all-day event. NASA’s Fermi spacecraft triggered on multiple gamma-ray episodes from the same patch of sky over several hours, and other satellites soon reported compatible detections. Compared to the known population of GRBs that have been studied for decades, this was an outlier beast of a different species.

At first, the event’s location near the crowded plane of the Milky Way made it tempting to suspect something closer to home, located in our own Galaxy. But follow-up imaging overturned that assumption. Observations with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile narrowed down the position and, together with Hubble and JWST, revealed that the transient was coincident with a dusty, irregular host galaxy. The distance is extreme: the light from the explosion began its journey roughly 8 billion years ago. In other words, whatever happened was not a local flare—it was a truly cosmic-scale detonation, or, rather, a string of detonations.

The duration of this event was not the only weird thing about it. Archival data showed that low-energy X-rays were already present almost a day before the main gamma-ray fireworks—an “X-ray precursor” that is hard to reconcile with standard models of GRBs. Meanwhile, the gamma-ray behavior itself looked like a stuttering engine. Fermi detected a sequence of short flares separated by long gaps, collectively implying multi-hour activity from a central engine rather than the single, clean explosion typical of such events.