Researchers at University of Tsukuba have developed a noncontact vibration measurement method using an event camera, a sensing technology inspired by biological vision. By applying geometric analysis to event-stream data, the team succeeded in reconstructing vibrations—an achievement that had posed substantial challenges using an event camera.

Category: electronics

Triglycerides induce endoplasmic reticulum lipid bilayer stress to activate PERK and enhance antifungal immunity

Fungal infections present persistent therapeutic challenges in immunocompromised populations, including individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), organ transplant recipients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, long-term hospitalized patients, patients with cancer, and those receiving immunomodulatory agents.1 These infections demonstrate remarkable recalcitrance to conventional therapies, compounded by fungal adaptability to environmental stresses, the emergence of drug-resistant strains, and the limited availability of clinically available antifungal agents.2 Systemic fungemia has alarmingly high mortality rates, accounting for approximately 1.5 million annual deaths worldwide, a burden comparable to AIDS-and tuberculosis-related mortality.3 Candida albicans is the most frequently isolated fungal pathogen in clinical settings. Despite therapeutic advances, invasive candidiasis persists with mortality rates exceeding 40%,4 underscoring the urgent need to elucidate host immune mechanisms against fungal pathogens.

When innate immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils, encounter fungi, the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on their surface recognize evolutionarily conserved fungal cell wall components, including β-glucan and α-mannan (classified as pathogen-associated molecular patterns), thereby initiating downstream signaling cascades and immune responses. The primary PRRs involved in fungal recognition are C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) and Toll-like receptors. The CLR family comprises Dectin-1 (specific for β-glucan), Dectin-2/3 (mannan sensors), Mincle, dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-grabbing nonintegrin, and CD23.5 Upon ligand binding, CLRs initiate the phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif within the Dectin-1 cytoplasmic tail and the recruitment of the Fc receptor γ-chain to Dectin-2 or Mincle, which serves as a docking site for spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK).

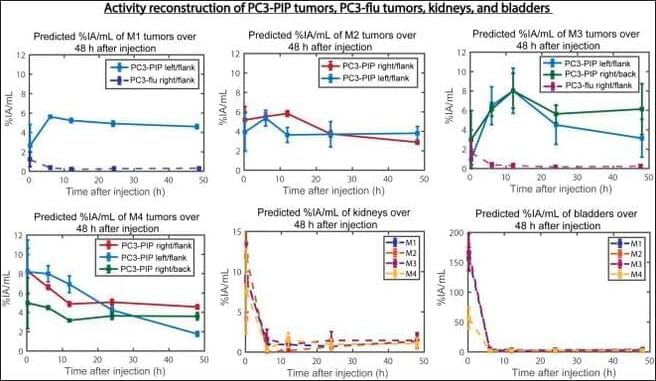

Continuous, Preclinical Activity Reconstruction in 177Lu-based Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Using a Sparse Uncollimated γ-Sensor Network

This RedJournal article presents a first step towards continuous dosimetry in targeted radiopharmaceutical therapy by developing a sparse sensor system to reconstruct continuous time-activity curves in preclinical 177Lu-based therapies, demonstrating high accuracy with short scan times.

177Lu-based radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) has shown increasing promise in the treatment of neuroendocrine and metastatic prostate cancer. Delivering optimal radiation dose to tumors while minimizing dose to organs-at-risk (OAR) remains an unmet need due to significant patient-to-patient heterogeneity in treatment response, necessitating multiple snapshots of the in vivo activity distribution. Towards this goal, here we present a high temporal-resolution activity reconstruction method demonstrated on preclinical prostate cancer models.

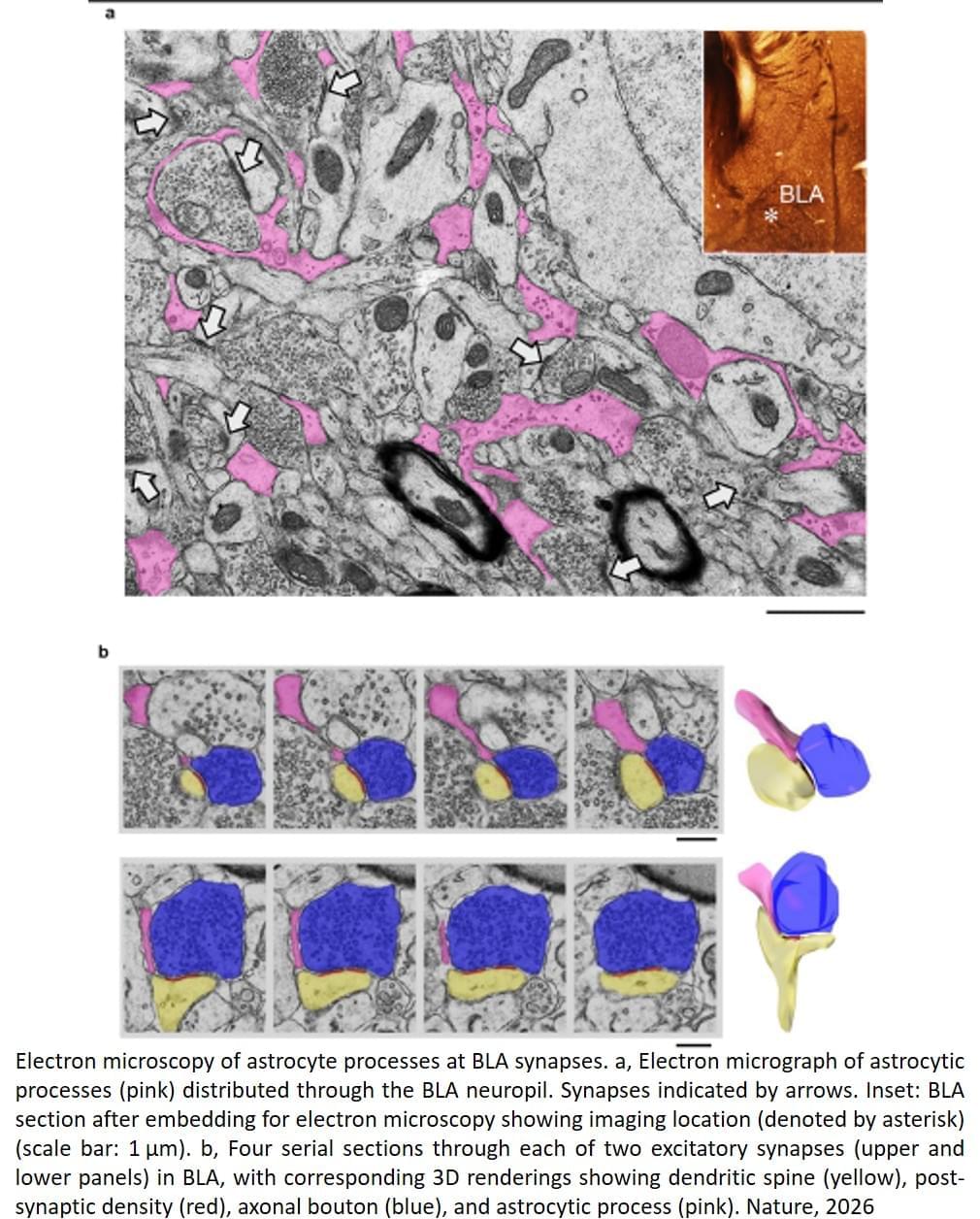

Astrocytes are critical for fear memory

The team used a mouse model to understand how fear learning as a mechanism takes place in the brain, how fear-related memories can be retrieved, and the contribution of neurons versus astrocytes to fear learning.

Using fluorescent activity sensors, the team watched astrocytes respond in real time as fear memories were formed and later retrieved. As those memories were extinguished, astrocyte activity diminished. When the researchers then selectively increased or suppressed the signals astrocytes send to neighboring neurons, the strength of fear memories shifted in parallel, demonstrating that astrocytes are not just passive bystanders, but active participants in shaping fear.

Change in astrocyte activity also influenced neural circuits. When the astrocyte activity was disrupted, neurons could no longer form normal fear-related activity patterns and effectively transmit information about appropriate defensive reactions to brain regions that help control defensive behavior. These findings challenge neuron-centric models of fear by showing that fear memories aren’t produced by neurons alone.

The impact of disrupting astrocytes rippled beyond the amygdala. The manipulations also influenced how fear signals were relayed to the prefrontal cortex, a brain region that is key for decision-making. This suggests that astrocytes not only influence encoding of fear memories by the amygdala, but also how the brain uses those memories to determine appropriate responses to fearful situations.

Knowing that astrocytes play a key role in the retrieval of fear memories will reshape therapeutic interventions for disorders driven by persistent fearful memories such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders and phobias, the author said. If astrocytes help determine whether fear memories are expressed or successfully extinguished, then targeting astrocyte-related pathways, rather than neural pathways, could eventually complement neuron-focused therapies.

Picture a star-shaped cell in the brain, stretching its spindly arms out to cradle the neurons around it. That’s an astrocyte, and for a long time, scientists thought its job was caretaking the brain, gluing together neurons, and maintaining neural circuits.

Sea urchin spines inspire self-powered underwater sensors

Nature does it again! The natural world has a knack for giving us the blueprints for some useful technologies, and the humble sea urchin is the latest contributor. Scientists have designed a new class of smart sensors by mimicking the internal architecture found in their spines.

Sea urchins are covered in movable spines that have long been thought of as a form of deterrent and protection against predators. But according to a new study published in the journal Nature, they are also sophisticated sensing tools.

Shield and sensor.

New diamond growth method slashes device temperatures by 41°F

What started as a fun experiment to create a decorative diamond “owl” for distinguished guests has evolved into a scalable manufacturing process for electronics.

Researchers at Rice University have developed a bottom-up method for growing patterned diamond surfaces to cool electronics.

The technique enables diamonds to be integrated directly into devices, reducing operating temperatures by 23°C (41°F).

1Campaign platform helps malicious Google ads evade detection

A newly identified cybercrime service known as 1Campaign is enabling threat actors to run malicious Google Ads that remain online for extended periods while evading scrutiny from security researchers.

1Campaign is a cloaking service that passes Google’s screening process and shows malicious content only to real potential victims. Security researchers and automated scanners are served benign white pages.

The operation has been active for at least three years and is managed by a developer using the name ‘DuppyMeister,’ according to a report from data security company Varonis.