Key cytoplasmic sensors, including the RNA sensors RIG-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), along with the DNA sensor cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), specifically recognize viral RNA and DNA.6,7 Upon nucleic acid detection, PRR adaptors (TRIF, MAVS, and STING) recruit kinases such as TBK1 and IKKε to initiate downstream signaling cascades.8,9,10 This process leads to the phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which subsequently translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to trigger type I interferon (IFN-I; IFN-α/β) expression.11,12,13 The secreted IFNs then activate pathways that culminate in the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), establishing an antiviral state in host cells.13

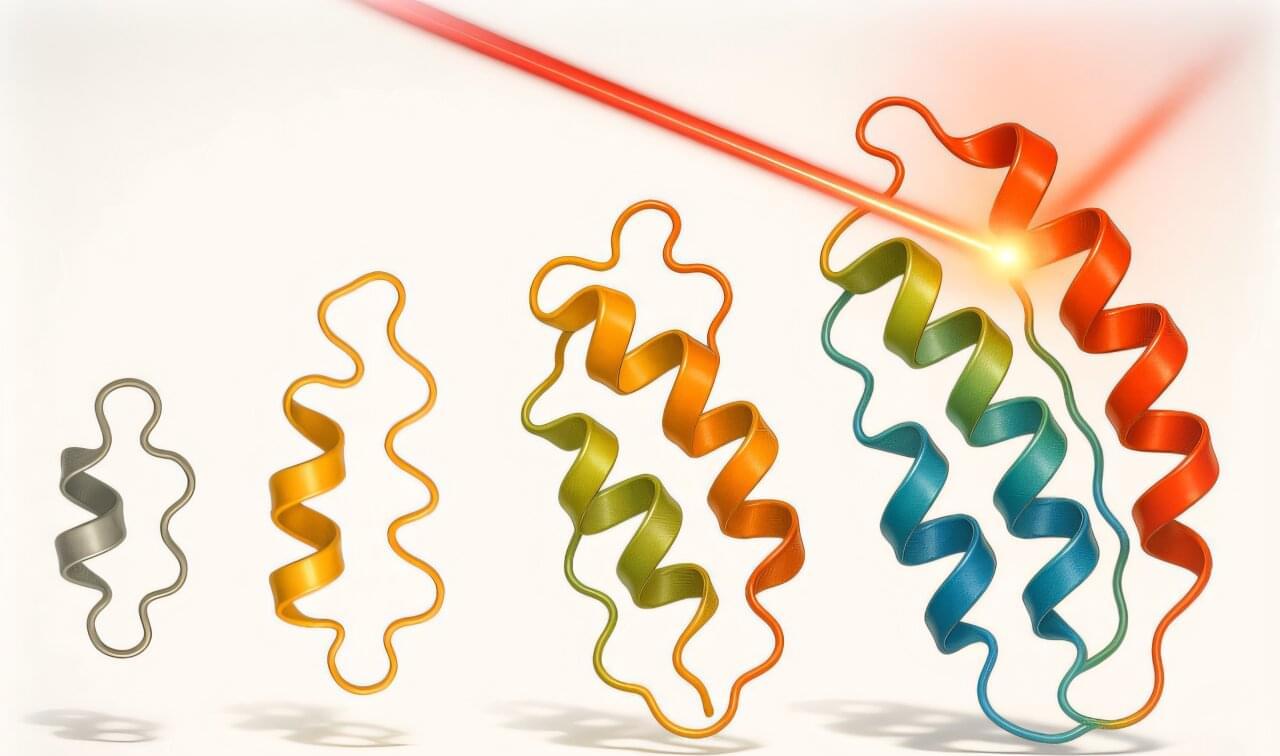

Guanine nucleotide exchange factor H1 (GEF-H1), encoded by Arhgef2, is a microtubule-associated protein (MAP) and plays a pivotal role in diverse cellular processes, including epithelial barrier permeability, cell cycle regulation, cell motility, polarization, and leukemic cell differentiation.14 Beyond its structural role, GEF-H1 contributes to inflammatory cytokine production, intracellular mycobacterial elimination, and macrophage-mediated antiviral defenses.15,16 Activation of GEF-H1 enhances RLR signaling through its interaction with TBK1, thereby promoting IFN-β induction in macrophages via a microtubule-dependent mechanism.15 Its regulation also extends beyond microtubule binding and involves phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms and dynamic protein-protein interactions.17,18,19,20,21,22,23 The RhoA-specific GEF activity of GEF-H1 is inhibited by its phosphorylation at Ser886 and Ser959, which is mediated by microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 2 (MARK2).24 Notably, here, MARK2 was also screened out to interact with GEF-H1 by immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry (IP-MS) assays in A549 cells. MARK2 belongs to the evolutionarily conserved KIN1/PAR-1/MARK family of serine/threonine kinases, which are crucial for microtubule stability and cellular polarity from yeast to humans.25 All mammalian MARK family members (MARK1–4) share a conserved architecture, featuring an N-terminal catalytic domain, a central ubiquitin-associated domain, and a C-terminal kinase-associated domain.26,27 These kinases regulate microtubule dynamics by phosphorylating key MAPs, including TAU, MAP2, and MAP4.28,29 However, their roles in viral infections remain poorly understood.30

Given the importance of phosphorylation-dependent signaling in antiviral responses, we hypothesized that MARK2 may modulate innate immunity through interacting with GEF-H1. To test this, we employed a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches, including MS-based interactome profiling, reporter gene assays, gene editing via CRISPR-Cas9, in vitro kinase assays, viral infection models in primary macrophages and cell lines, and mouse models of RNA and DNA virus infection. By elucidating the functional significance of the MARK2-GEF-H1-TBK1 signaling axis, this study aims to reveal a previously uncharacterized layer of innate immune regulation and identify potential targets for broad-spectrum antiviral strategies.