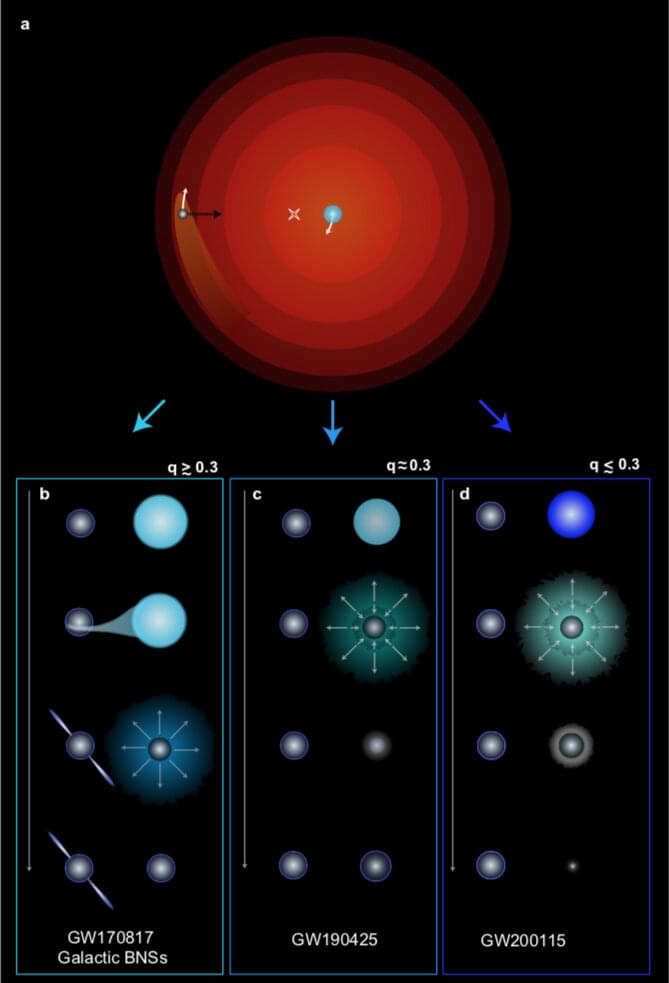

A new study showing how the explosion of a stripped massive star in a supernova can lead to the formation of a heavy neutron star or a light black hole resolves one of the most challenging puzzles to emerge from the detection of neutron star mergers by the gravitational wave observatories LIGO and Virgo.

The first detection of gravitational waves by the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in 2017 was a neutron star merger that mostly conformed to the expectations of astrophysicists. But the second detection, in 2,019 was a merger of two neutron stars whose combined mass was unexpectedly large.

“It was so shocking that we had to start thinking about how to create a heavy neutron star without making it a pulsar,” said Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.