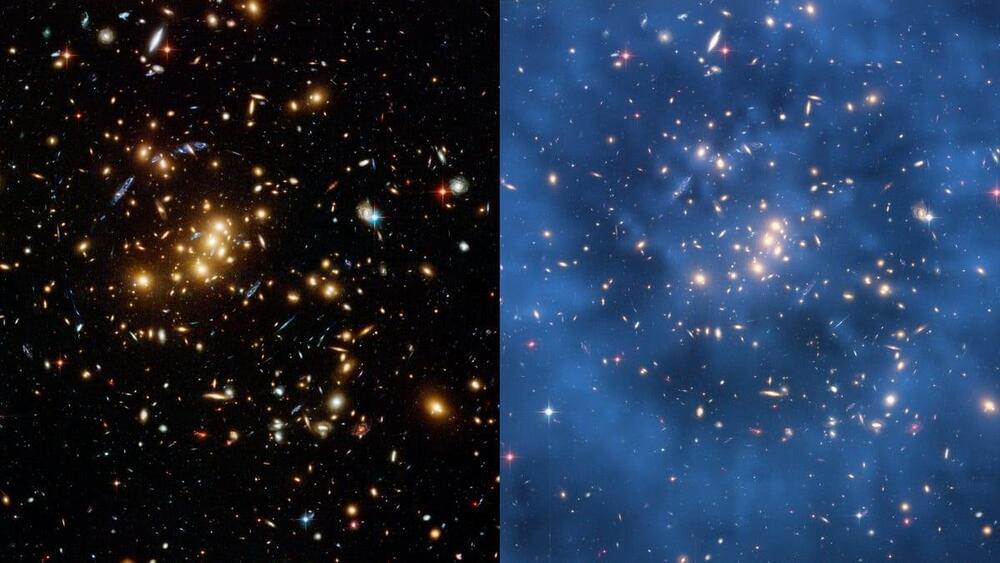

Lensing of the cosmic microwave background indicates 12-billion-year-old galaxies had dark matter.

Scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) Energetic Materials Center and Purdue University Materials Engineering Department have used simulations performed on the LLNL supercomputer Quartz to uncover a general mechanism that accelerates chemistry in detonating explosives critical to managing the nation’s nuclear stockpile. Their research is featured in the July 15 issue of the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

Insensitive high explosives based on TATB (1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene) offer enhanced safety properties over more conventional explosives, but physical explanations for these safety characteristics are not clear. Explosive initiation is understood to arise from hotspots that are formed when a shockwave interacts with microstructural defects such as pores. Ultrafast compression of pores leads to an intense localized spike in temperature, which accelerates chemical reactions needed to initiate burning and ultimately detonation. Engineering models for insensitive high explosives—used to assess safety and performance—are based on the hotspot concept but have difficulty in describing a wide range of conditions, indicating missing physics in those models.

Using large-scale atomically resolved reactive molecular dynamics supercomputer simulations, the team aimed to directly compute how hotspots form and grow to better understand what causes them to react.

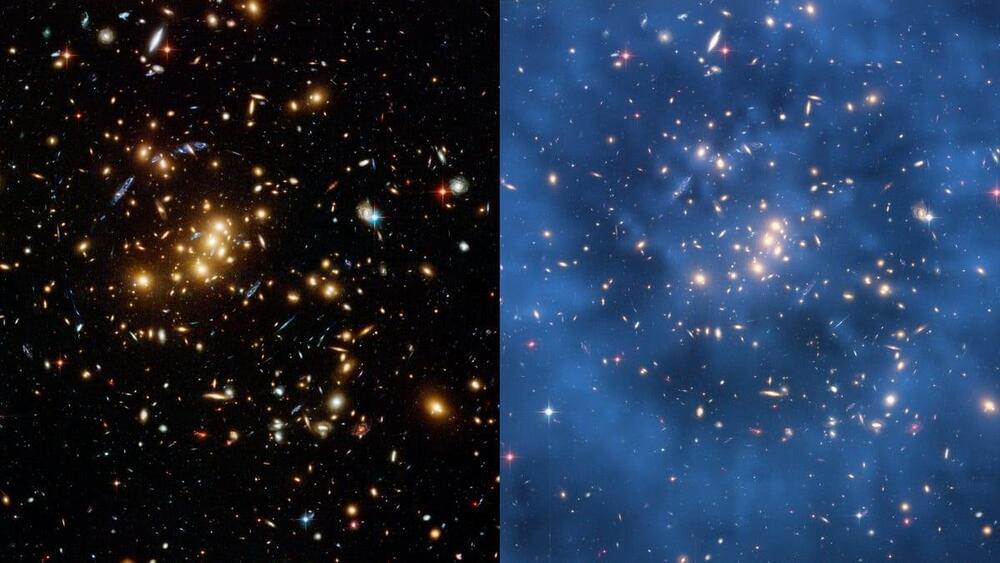

Dwarf galaxies are small galaxies composed of a few billion stars. They are challenging to detect due to their low luminosity, low mass, and small size. However, it remains elusive how these dwarf and giant galaxies assemble their stars and evolve into modern-day galaxies.

India’s first dedicated multi-wavelength space observatory, AstroSat, cracked this mystery. A team of scientists using AstroSat shows how the star-forming complexes in the outskirts of a dwarf galaxy migrate towards the central region and contribute to its growth in mass and luminosity.

The team includes astronomers from India, the USA, and France. Professor Kanak Saha at the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), Pune, conceived this study. Mr. Anshuman Borgohain is the lead author of the paper.

What is dark matter? Does it even exist, or do we just need an adjustment to our theory of gravity?

What is dark matter? It has never been observed, yet scientists estimate that it makes up 85% of the matter in the universe. The short answer is that no one knows what dark matter is. More than a century ago, Lord Kelvin offered it as an explanation for the velocity of stars in our own galaxy. Decades later, Swedish astronomer Knut Lundmark noted that the universe must contain much more matter than we can observe. Scientists since the 1960s and ’70s have been trying to figure out what this mysterious substance is, using ever-more complicated technology. However, a growing number of physicists suspect that the answer may be that there is no such thing as dark matter at all.

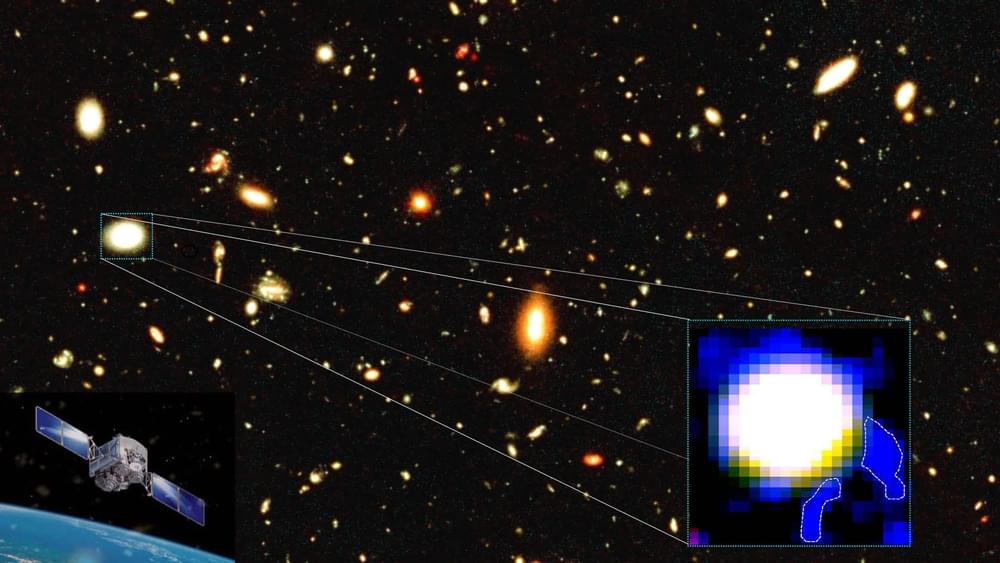

Scientists can observe far-away matter in a number of ways. Equipment such as the famous Hubble telescope measures visible light while other technology, such as radio telescopes, measures non-visible phenomena. Scientists often spend years gathering data and then proceed to analyze it to make the most sense of what they are seeing.

Artificial Intelligence has ushered the advancement of several disciplines throughout the years. But could it ever discover a new form of physics?

A group of roboticists from Columbia University wanted to exploit the vast potential of AI and find out if it can ever find an “alternative physics.”

Hence, they created an AI tool that could recognize physical occurrences and identify pertinent variables, essential building blocks for every physics theory.

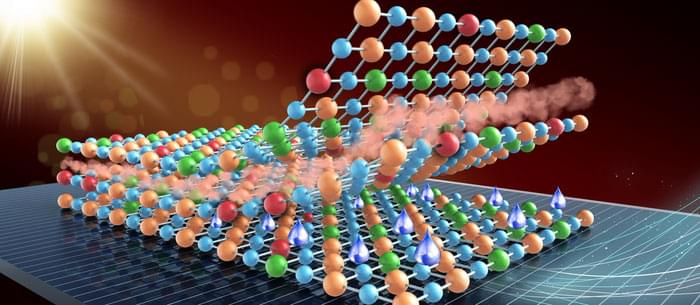

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are promising solar technologies. Although low-cost wet processing has shown advantages in small-area PSC fabrication, the preparation of uniform charge transport layers with thickness of several nanometers from solution for meter-sized large area products is still challenging.

Recently, a research group led by Prof. LIU Shengzhong from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) has developed a facile surface redox engineering (SRE) strategy for vacuum-deposited NiO x to match the slot-die-coated perovskite, and fabricated high-performance large-area perovskite submodules.

This work was published in Joule (“Surface redox engineering of vacuum-deposited NiO x for top-performance perovskite solar cells and modules”).

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/mlst.

Discord: https://discord.gg/ESrGqhf5CB

The field of Artificial Intelligence was founded in the mid 1950s with the aim of constructing “thinking machines” — that is to say, computer systems with human-like general intelligence. Think of humanoid robots that not only look but act and think with intelligence equal to and ultimately greater than that of human beings. But in the intervening years, the field has drifted far from its ambitious old-fashioned roots.

Dr. Ben Goertzel is an artificial intelligence researcher, CEO and founder of SingularityNET. A project combining artificial intelligence and blockchain to democratize access to artificial intelligence. Ben seeks to fulfil the original ambitions of the field. Ben graduated with a PhD in Mathematics from Temple University in 1990. Ben’s approach to AGI over many decades now has been inspired by many disciplines, but in particular from human cognitive psychology and computer science perspective. To date Ben’s work has been mostly theoretically-driven. Ben thinks that most of the deep learning approaches to AGI today try to model the brain. They may have a loose analogy to human neuroscience but they have not tried to derive the details of an AGI architecture from an overall conception of what a mind is. Ben thinks that what matters for creating human-level (or greater) intelligence is having the right information processing architecture, not the underlying mechanics via which the architecture is implemented.

Ben thinks that there is a certain set of key cognitive processes and interactions that AGI systems must implement explicitly such as; working and long-term memory, deliberative and reactive processing, perc biological systems tend to be messy, complex and integrative; searching for a single “algorithm of general intelligence” is an inappropriate attempt to project the aesthetics of physics or theoretical computer science into a qualitatively different domain.

Panel: Dr. Tim Scarfe, Dr. Yannic Kilcher, Dr. Keith Duggar.

Pod version: https://anchor.fm/machinelearningstreettalk/episodes/58-Dr–…e-e15p20i.

Why we need AI to compete against each other. Does a Great Filter Stop all Alien Civilizations at some point? Are we Doomed if We Find Life in Our Solar System?

David Brin is a scientist, speaker, technical consultant and world-known author. His novels have been New York Times Bestsellers, winning multiple Hugo, Nebula and other awards.

A 1998 movie, directed by Kevin Costner, was loosely based on his book The Postman.

His Ph.D in Physics from UCSD — followed a masters in optics and an undergraduate degree in astrophysics from Caltech. He was a postdoctoral fellow at the California Space Institute and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Brin serves on advisory committees dealing with subjects as diverse as national defense and homeland security, astronomy and space exploration, SETI and nanotechnology, future/prediction and philanthropy. He has served since 2010 on the council of external advisers for NASA’s Innovative and Advanced Concepts group (NIAC), which supports the most inventive and potentially ground-breaking new endeavors.

https://www.davidbrin.com/books.html.

https://twitter.com/DavidBrin.

https://www.newsweek.com/soon-humanity-wont-alone-universe-opinion-1717446

Youtube Membership: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCz3qvETKooktNgCvvheuQDw/join.

Podcast: https://anchor.fm/john-michael-godier/subscribe.

Apple: https://apple.co/3CS7rjT

More JMG

https://www.youtube.com/c/JohnMichaelGodier.

Want to support the channel?

A new AI program observed physical phenomena and uncovered relevant variables—a necessary precursor to any physics theory.

An AI shown videos of physical phenomena and instructed to identify the variables involved produced answers different from our own.