New LISA satellite trio will be able to detect the forgotten ‘middle children’ of the black hole family.

Category: physics – Page 141

Would We Want to Live Forever?

More deathism from Mr Tyson. Really I’m a big fan but I dislike this sort of thinking. I commented on the vid.

What if we could live forever? Neil deGrasse Tyson takes us through life and death: if we could live forever what would life really mean? We explore why fresh flowers have meaning and why dogs make every day count. Learn about the Cretaceous-Tertiary Event, The Permian-Triassic Extinction, The Holocene Epoc, and how Earth is one killing machine.

Get the NEW StarTalk book, ‘To Infinity and Beyond: A Journey of Cosmic Discovery’ on Amazon: https://amzn.to/3PL0NFn.

Support us on Patreon: / startalkradio.

FOLLOW or SUBSCRIBE to StarTalk:

Major physics publishers join forces to announce ‘purpose-led’ publishing initiative

The recent move to open access, in which researchers pay a fee to publish an article in a journal, has also encouraged some publishers to boost revenues by publishing as many papers as possible. At the same time, there has been a rise in retractions, especially of fabricated or manipulated manuscripts sold by “paper mills”. Last year, for example, more than 10 000 journal articles were retracted – a record high – with about 8,000 alone from journals owned by Hindawi, a London-based subsidiary of the publicly-owned publisher Wiley.

The new “purpose-led” coalition is designed to show how the three learned-society publishers have a business model that is not like that of profit-focussed corporations. In particular, they plough all the money generated from publishing back into science by supporting initiatives such as educational training, mentorship, awards and grants. “Purpose-led publishing is about our dedication to science, and to the scientific community,” says Antonia Seymour, IOP Publishing’s chief executive. “We’re proudly declaring that science is our only shareholder.”

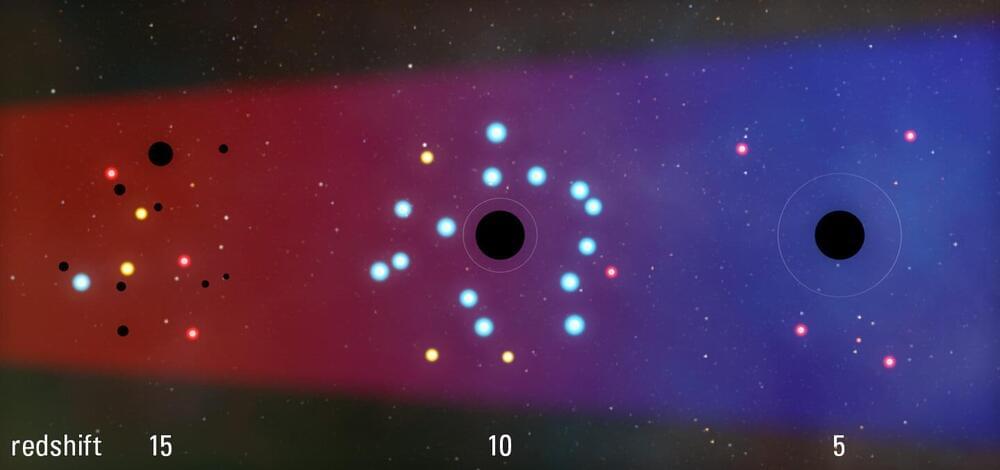

New findings from JWST: How black holes switched from creating to quenching stars

Astronomers have long sought to understand the early universe, and thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), a critical piece of the puzzle has emerged. The telescope’s infrared detecting “eyes” have spotted an array of small, red dots, identified as some of the earliest galaxies formed in the universe.

This surprising discovery is not just a visual marvel, it’s a clue that could unlock the secrets of how galaxies and their enigmatic black holes began their cosmic journey.

“The astonishing discovery from James Webb is that not only does the universe have these very compact and infrared bright objects, but they’re probably regions where huge black holes already exist,” explains JILA Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder astrophysics professor Mitch Begelman. “That was thought to be impossible.”

Scientists Have Solved the 141-Year-Old ‘Reverse Sprinkler’ Problem

This brain-teaser has baffled physicists since 1883. Thanks to some innovative engineering, it finally makes sense.

Newly-developed light amplifying ‘photonic time crystals’ may improve lasers and telecoms

The idea of time crystals sparked much controversy and skepticism among physicists, who doubted such a phenomenon could ever be observed.

These ‘photonic time crystals’ can amplify microwave frequencies, but the team that developed them is confident they could work on longer wavelengths too.

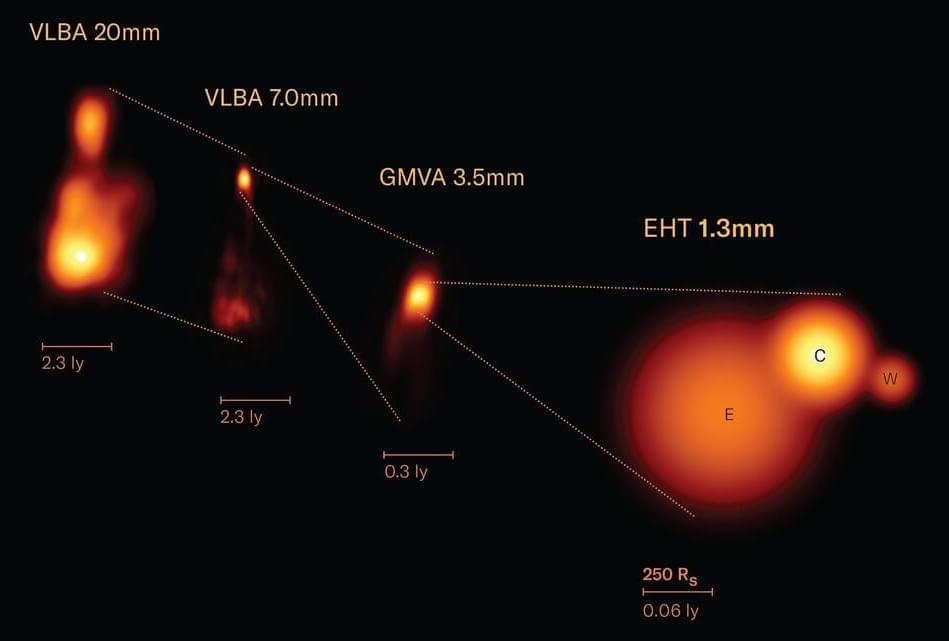

Magnetic launch of black hole jets in Perseus A

The Event Horizon Telescope collaboration, including scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, has recently resolved the jet base of an evolving jet of plasma at ultra-high angular resolution.

The international team of scientists used the Earth-size telescope to probe the magnetic structure in the nucleus of the radio galaxy 3C 84 (Perseus A), one of the closest active supermassive black holes in our cosmic neighborhood.

These novel results provide new insight into how jets are launched, revealing that in this cosmic tug of war, the magnetic fields overpower gravity. The study is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Ghost in the Cosmos: Almost Invisible Galaxy Challenges Dark Matter Model

A group of astrophysicists led by Mireia Montes, a researcher at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), has discovered the largest and most diffuse galaxy recorded until now. The study has been published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, and has used data taken with the Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) and the Green Bank Radiotelescope (GBT).

Nube is an almost invisible dwarf galaxy discovered by an international research team led by the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) in collaboration with the University of La Laguna (ULL) and other institutions.

The name was suggested by the 5-year-old daughter of one of the researchers in the group, and is due to the diffuse appearance of the object. Its surface brightness is so faint that it had passed unnoticed in the various previous surveys of this part of the sky, as if it were some kind of ghost. This is because its stars are so spread out in such a large volume that “Nube” (the Spanish for “Cloud”) was almost undetectable.

MIT physicists turn pencil lead into “gold”

MIT physicists have metaphorically turned graphite, or pencil lead, into gold by isolating five ultrathin flakes stacked in a specific order. The resulting material can then be tuned to exhibit three important properties never before seen in natural graphite.

“It is kind of like one-stop shopping,” says Long Ju, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and leader of the work, which is reported in the Oct. 5 issue of Nature Nanotechnology. “Nature has plenty of surprises. In this case, we never realized that all of these interesting things are embedded in graphite.”

Further, he says, “It is very rare material to find materials that can host this many properties.”