Simultaneously detecting the gravitational-wave and neutrino signals emitted during the last second of a massive star’s life could show how such stars die.

A new electron-scattering experiment challenges our understanding of the first excited state of the helium nucleus.

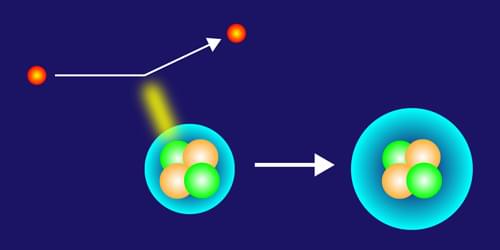

A helium nucleus, also known as an particle, consists of two protons and two neutrons and is one of the most extensively studied atomic nuclei. Given the small number of constituents, the particle can be accurately described by first principles calculations. And yet, the excited states of the particle remain a bit of a mystery, as evidenced by a disagreement surrounding the excitation from the ground state 01+ to the first excited state 02+ [1]. Theoretical predictions for this transition do not match measurements, but the experimental uncertainties have been too large for implications to be drawn. Now, the A1 Collaboration at Mainz Microtron (MAMI) in Germany has remeasured this transition via inelastic electron scattering [2]. The new data significantly improves the precision compared to previous measurements and confirms the initial discrepancy.

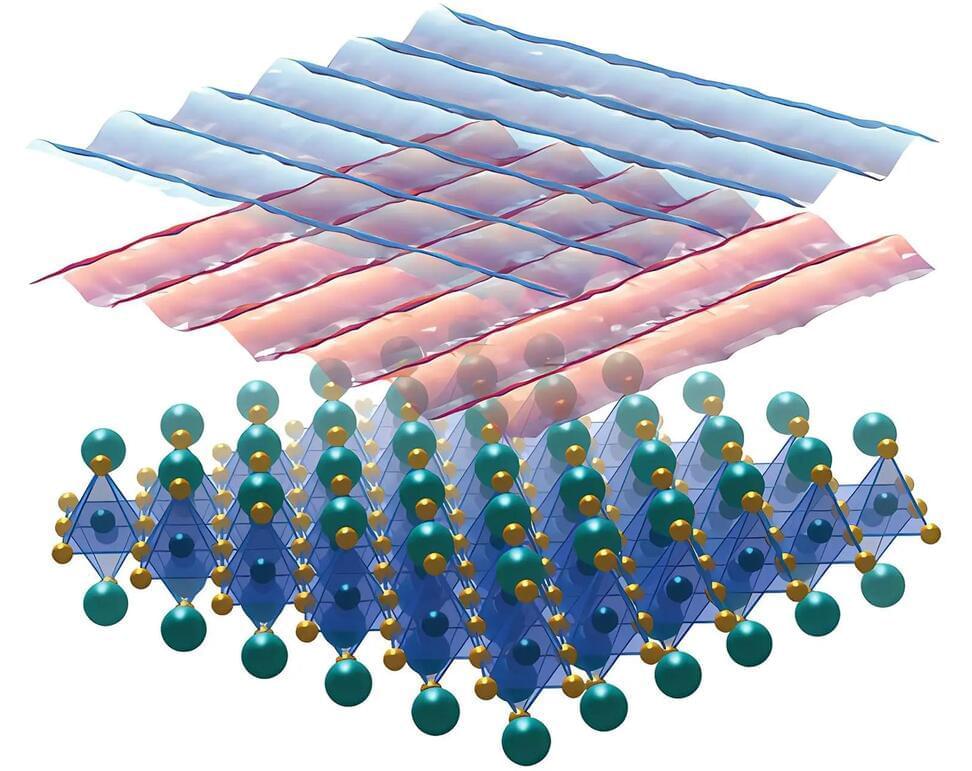

Hidden stripes in a crystal could help scientists understand the mysterious behavior of electrons in certain quantum systems, including high-temperature superconductors, an unexpected discovery by RIKEN physicists suggests.

The electrons in most materials interact with each other very weakly. But physicists often observe interesting properties in materials in which electrons strongly interact with each other. In these materials, the electrons often collectively behave as particles, giving rise to ‘quasiparticles’.

“A crystal can be thought of like an alternative universe with different laws of physics that allow different fundamental particles to live there,” says Christopher Butler of the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science.

Imperial physicists have performed the double-slit experiment in time, using materials that can change optical properties in femtoseconds, providing insights into the nature of light and paving the way for advanced materials that can control light in both space and time.

Imperial physicists have recreated the famous double-slit experiment, which showed light behaving as particles and a wave, in time rather than space.

In a groundbreaking development, Imperial College London.

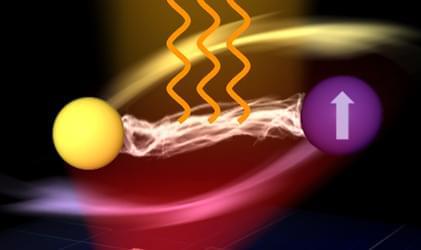

Magnetic spin excitations can combine with photons to produce exotic particles that emit laser-like microwaves.

One of the challenges for building systems for quantum computing and communications has been the lack of laser-like microwave sources that produce sufficient power but don’t require extreme cooling. Now a research team has demonstrated a new room-temperature technique for making coherent microwave radiation—the kind that comes from a laser [1]. The device exploits the interaction of a magnetic material with electromagnetic fields. The researchers expect that the work will lead to microwave sources that can be built into chips employed in future quantum devices.

The devices that store quantum bits for quantum computers often require microwave signals to input and retrieve data, so lasers operating at microwave frequencies (masers)—and other sources of coherent microwaves—could be very useful. But even though masers were invented before lasers, most maser technologies work only at ultracold temperatures. A 2018 design works at room temperature but doesn’t produce very much power [2].

Materials that can conduct negatively charged hydrogen atoms in ambient conditions could pave the way for advanced clean energy storage and electrochemical conversion technologies. A research team from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) demonstrated a technique that enables a room-temperature all-solid-state hydride cell by introducing and exploiting defects in the lattice structure of rare earth hydrides. Their study was published in Nature on April 5.

Solid materials that conduct lithium, sodium and hydrogen cations have been used in batteries and fuel cells. Under certain conditions, some of the materials transition to superionic states where ions move as fast as they do in liquids by skipping through the rigid crystal structure. This phenomenon is advantageous for chemical and energy conversions as it allows ions to move without a liquid or soft membrane to separate the electrodes. However, few solid-state materials can reach this state under ambient conditions.

“Materials that exhibit superionic conduction at ambient conditions would provide huge opportunities for constructing brand new all-solid-state hydride batteries, fuel cells and electrochemical cells for the storage and conversion of clean energy,” said Prof. Chen Ping, study author from DICP.

The first observation of collider neutrinos at the LHC paves the way for exploring new physics scenarios.

Although neutrinos are produced abundantly in collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), until now no neutrinos produced in such a way had been detected. Within just nine months of the start of LHC Run 3 and the beginning of its measurement campaign, the FASER collaboration changed this picture by announcing its first observation of collider neutrinos at this year’s electroweak session of the Rencontres de Moriond. In particular, FASER observed muon neutrinos and candidate events of electron neutrinos. “Our statistical significance is roughly 16 sigma, far exceeding 5 sigma, the threshold for a discovery in particle physics,” explains FASER’s co-spokesperson Jamie Boyd.

In addition to its observation of neutrinos at a particle collider, FASER presented results on searches for dark photons. With a null result, the collaboration was able to set limits on previously unexplored parameter space and began to exclude regions motivated by dark matter. FASER aims to collect up to ten times more data over the coming years, allowing more searches and neutrino measurements.

Erasing data perfectly and attaining the lowest possible temperature may appear unrelated, but they share a strong connection. Researchers at TU Wien have discovered a quantum formulation for the third law of thermodynamics.

The temperature of absolute zero.

Absolute zero is the theoretical lowest temperature on the thermodynamic temperature scale. At this temperature, all atoms of an object are at rest and the object does not emit or absorb energy. The internationally agreed-upon value for this temperature is −273.15 °C (−459.67 °F; 0.00 K).

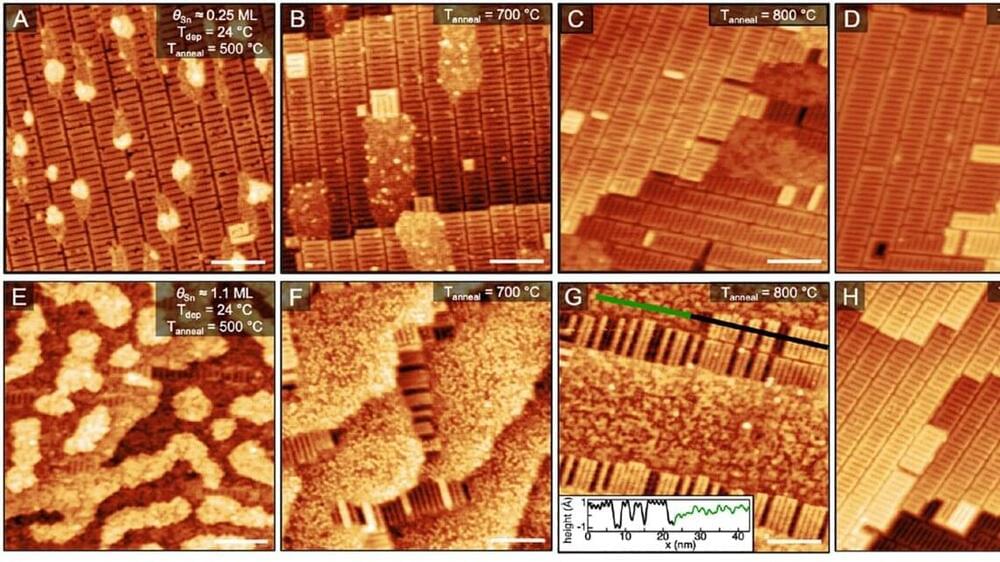

New research from a team of scientists at the Cornell University Center for Bright Beams has made significant strides in developing new techniques to guide the growth of materials used in next-generation particle accelerators.

The study, published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry C, reveals the potential for greater control over the growth of superconducting Nb3Sn films, which could significantly reduce the cost and size of cryogenic infrastructure required for superconducting technology.

Superconducting accelerator facilities, such as those used for X-ray free-electron laser radiation, rely on niobium superconducting radio frequency (SRF) cavities to generate high-energy beams. However, the associated cryogenic infrastructure, energy consumption, and operating costs of niobium SRF cavities limit access to this technology.