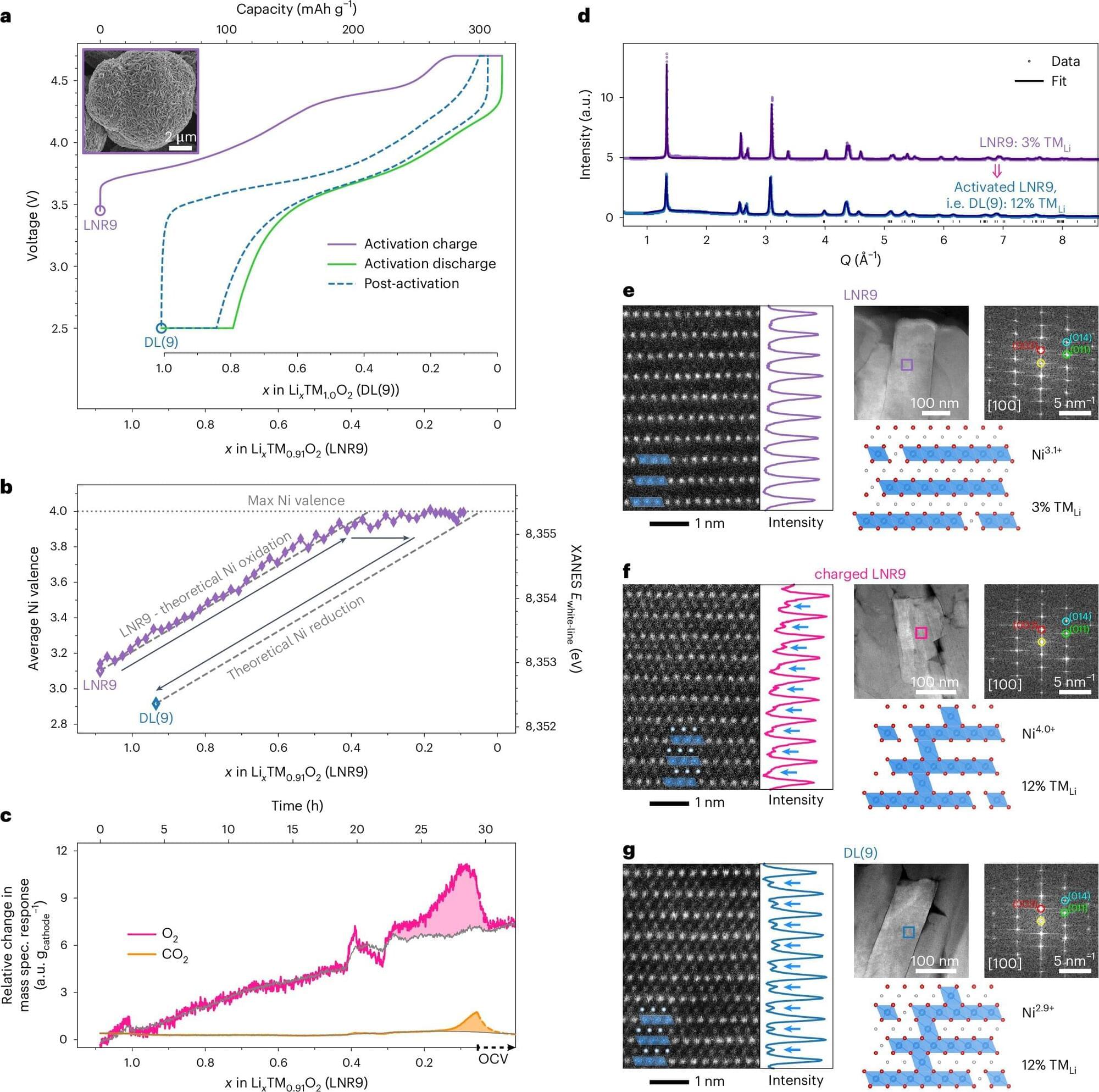

Lithium-ion batteries (LiBs) remain the most widely used rechargeable batteries worldwide, due to their light weight, high energy densities and their short charging times. Energy engineers have been trying to identify new materials and strategies that could help to further boost the energy stored by LiBs, while also extending their lifespan (i.e., the period for which they can be used reliably).

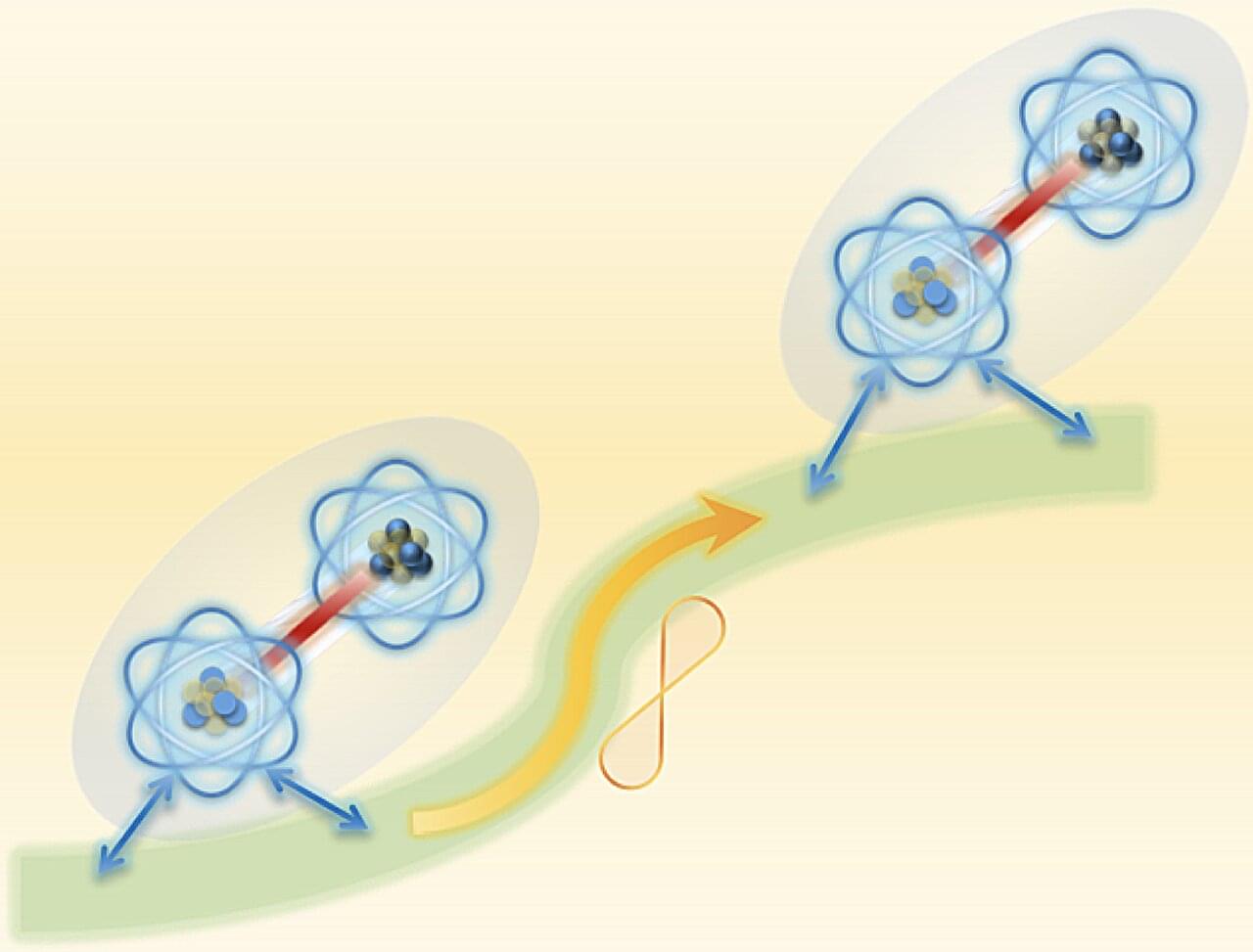

LiBs work by moving charged lithium atoms (i.e., ions) between a positive electrode (i.e., cathode) and a negative electrode (i.e., anode). When lithium ions enter and leave these materials, they can experience significant structural changes.

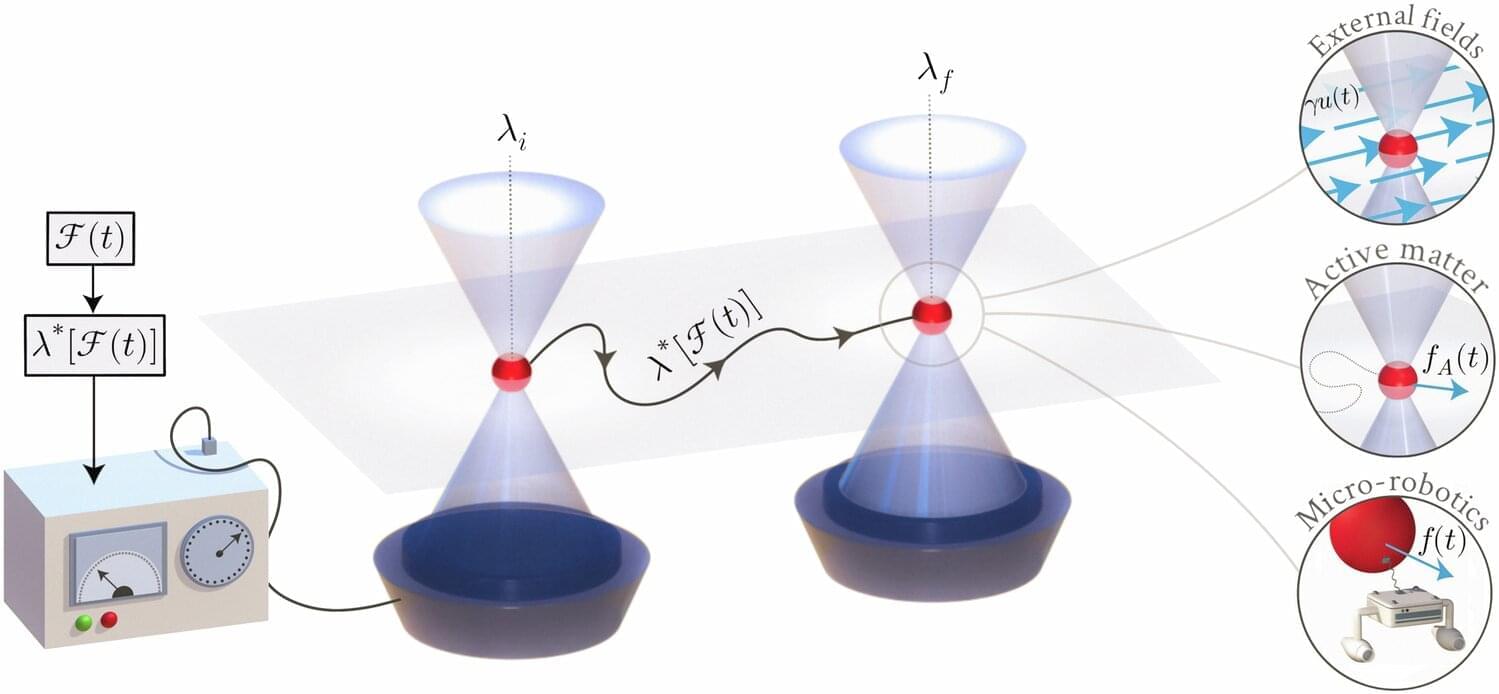

These changes include the sudden shrinkage of the spacing between the materials’ horizontal layers, which can be experimentally monitored through the crystal’s c-lattice parameter. This phenomenon, referred to as c-collapse, can deform the material, crack the particles and in turn shorten the life of batteries.