Researchers at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory are harnessing artificial intelligence and machine learning to enhance fusion energy production, tackling the challenge of controlling plasma reactions. Their innovations include optimizing the design and operation of containment vessels and using AI to predict and manage instabilities, significantly improving the safety and efficiency of fusion reactions. This technology has been successfully applied in tokamak reactors, advancing the field towards viable commercial fusion energy. Credit: SciTechDaily.com.

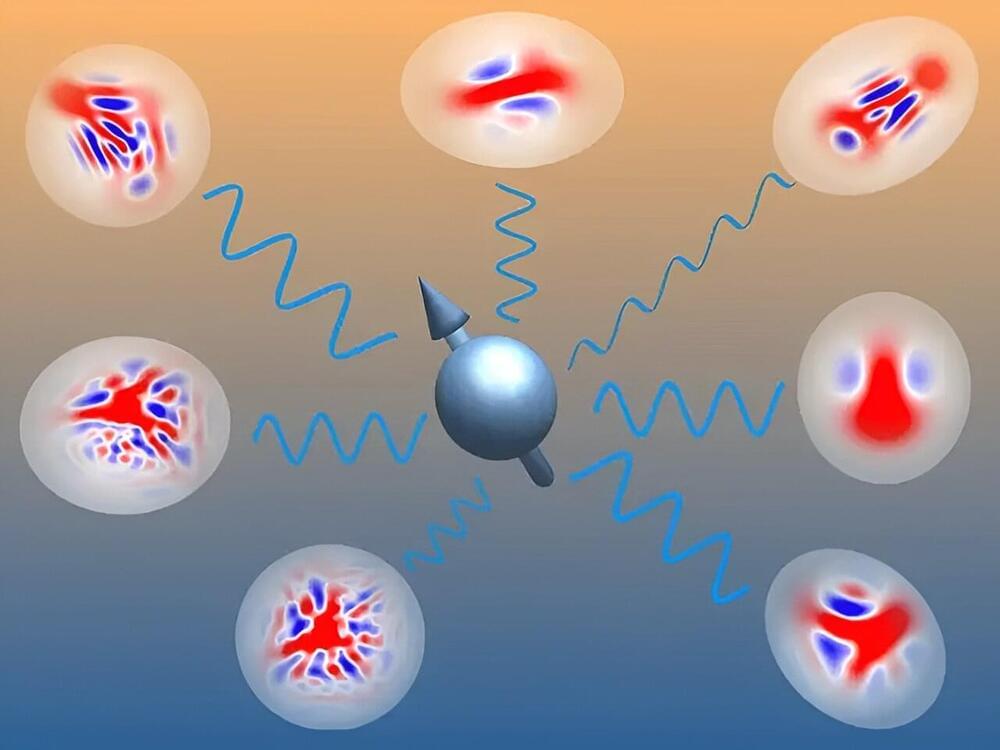

The intricate dance of atoms fusing and releasing energy has fascinated scientists for decades. Now, human ingenuity and artificial intelligence are coming together at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) to solve one of humankind’s most pressing issues: generating clean, reliable energy from fusing plasma.

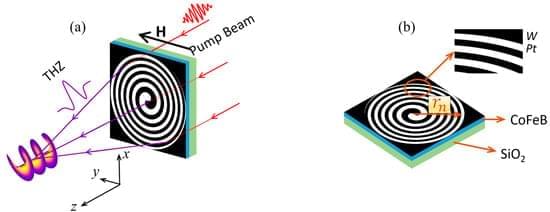

Unlike traditional computer code, machine learning — a type of artificially intelligent software — isn’t simply a list of instructions. Machine learning is software that can analyze data, infer relationships between features, learn from this new knowledge, and adapt. PPPL researchers believe this ability to learn and adapt could improve their control over fusion reactions in various ways. This includes perfecting the design of vessels surrounding the super-hot plasma, optimizing heating methods, and maintaining stable control of the reaction for increasingly long periods.