Researchers have characterized the temperature-induced frequency shifts of a thorium-229 nuclear transition—an important step in establishing thorium clocks as next-generation frequency standards.

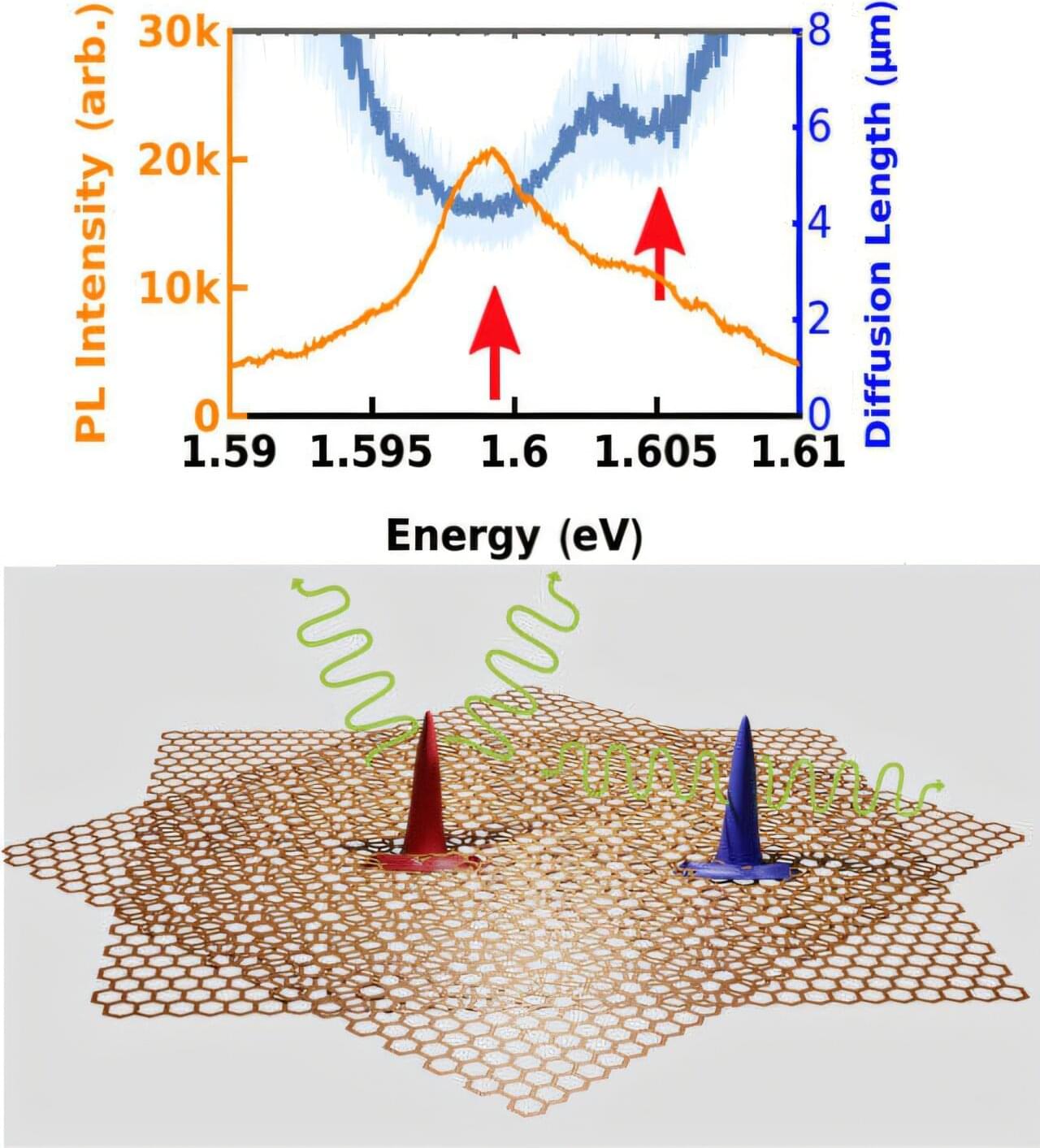

Atomic clocks are at the core of many scientific and technological applications, including spectroscopy, radioastronomy, and global navigation satellite systems. Today’s most precise devices—based on electronic transitions in atoms—would gain or lose less than 1 second over the age of the Universe. An even more accurate timekeeping approach has recently emerged, based on a clock ticking at the frequency of a nuclear transition of the isotope thorium-229 (229 Th) [1, 2]. Now a collaboration between the teams of Jun Ye of JILA, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the University of Colorado Boulder and of Thorsten Schumm of the Vienna Center for Quantum Science and Technology has characterized one of the main sources of the systematic uncertainties that might spoil a clock’s accuracy: temperature-induced shifts of the clock transition frequency [3].