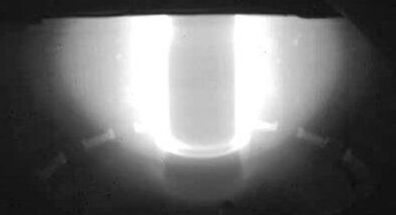

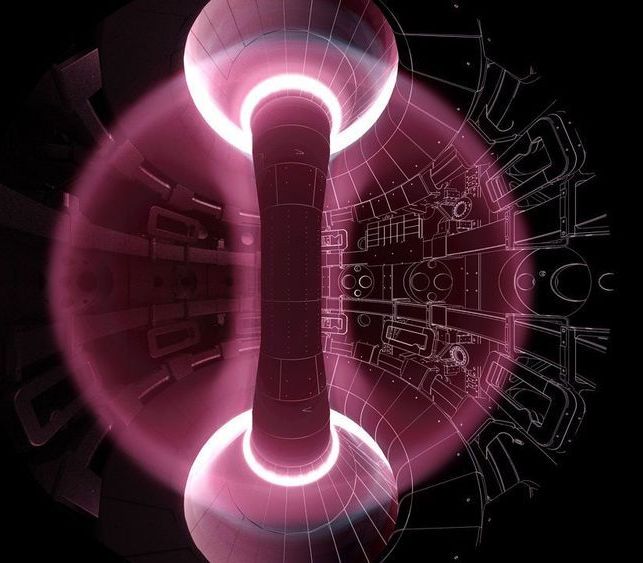

After a long, seven-year development, an experimental fusion reactor in the UK has been successfully powered on for the time, achieving ‘first plasma’: confirmation that all its components can work together to heat hydrogen gas into the plasma phase of matter.

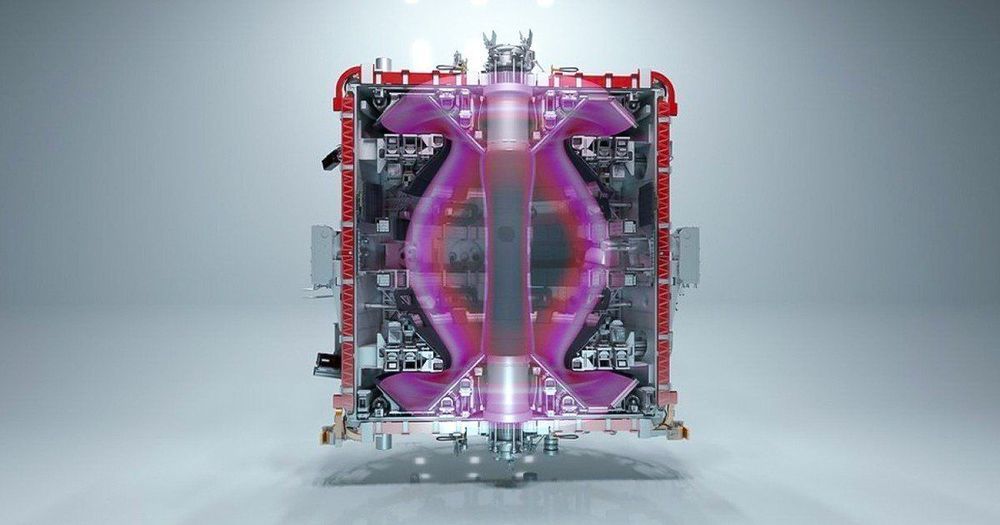

This transition – achieved last week by a machine called MAST Upgrade in Culham, Oxfordshire – is the fundamental ingredient of a working nuclear fusion reactor, a dream scientists have been trying to realise for decades.

In nuclear fusion, the nuclei of two or more lighter elements fuse into a heavier nucleus, and release energy. This phenomenon is what goes on in the heart of the Sun, and if we can recreate and maintain the same reactions on Earth at sufficient scale, we stand to reap the rewards of clean, virtually limitless, low-carbon energy.