Category: mobile phones – Page 148

A new review from the FDA says it finds no evidence linking the two, but that research should continue.

The findings: The report reviewed 125 experiments carried out on animals and 75 on humans between 2008 and August 2019. In summary, the FDA said that there’s “no consistent pattern” to link radiofrequency radiation, or RFR, to tumors or cancer.

Rats don’t use cell phones the way humans do. An overarching problem with the animal studies in the review is that they don’t mimic how humans actually use their phones. Animal studies often douse a rat’s entire body in radiation at levels that are far higher than what humans are normally exposed to when we use cell phones. The human studies were also flawed, relying only on questionnaires from family members or observational data.

When phones put PCs to shame.

Samsung’s recently launched top-of-the-line Galaxy S20 Ultra is the first smartphone ever to feature a whopping 16GB of LPDDR5 RAM.

Circa 2017

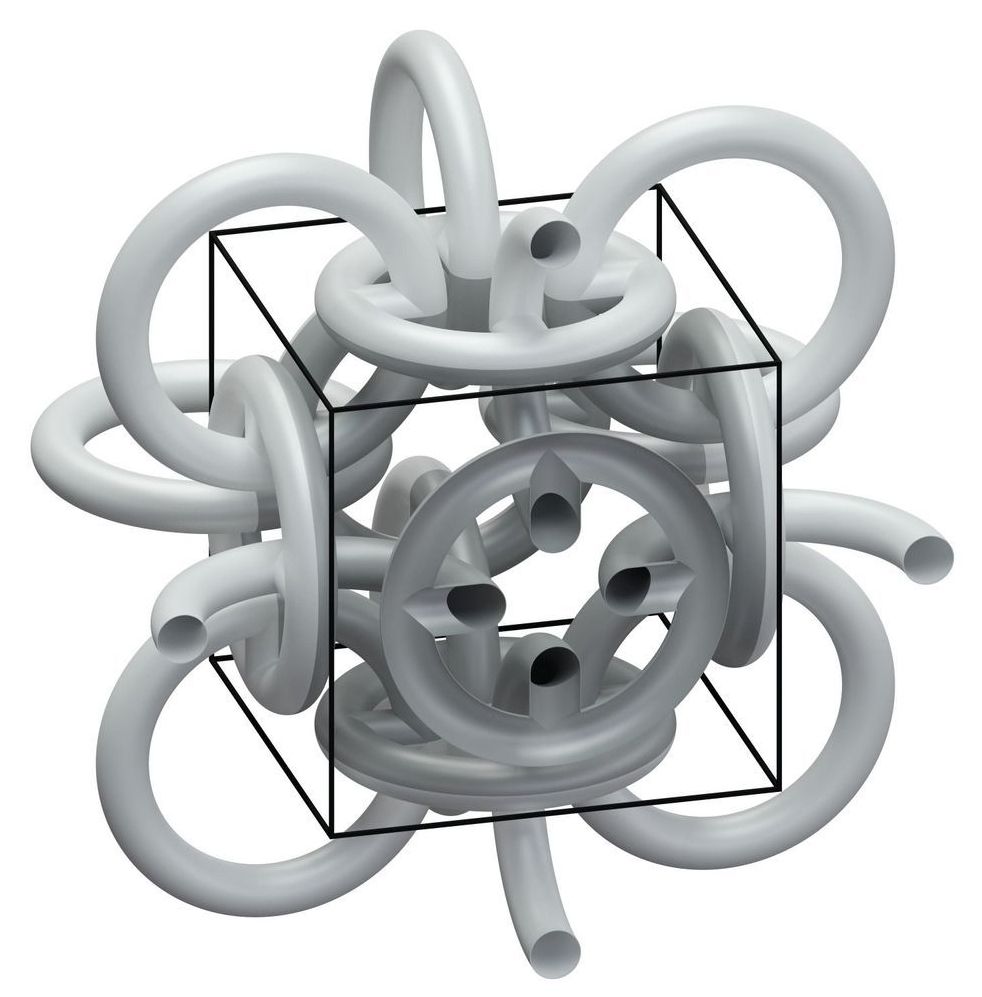

The Middle Ages certainly were far from being science-friendly: Whoever looked for new findings off the beaten track faced the threat of being burned at the stake. Hence, the contribution of this era to technical progress is deemed to be rather small. Scientists of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), however, were inspired by medieval mail armor when producing a new metamaterial with novel properties. They succeeded in reversing the Hall coefficient of a material.

The Hall effect is the occurrence of a transverse electric voltage across an electric conductor passed by current flow, if this conductor is located in a magnetic field. This effect is a basic phenomenon of physics and allows to measure the strength of magnetic fields. It is the basis of magnetic speed sensors in cars or compasses in smartphones. Apart from measuring magnetic fields, the Hall effect can also be used to characterize metals and semiconductors and in particular to determine charge carrier density of the material. The sign of the measured Hall voltage allows conclusions to be drawn as to whether charge carriers in the semiconductor element carry positive or negative charge.

Mathematicians already predicted theoretically that it is possible to reverse the Hall coefficient of a material (such as gold or silicon), i.e. to reverse its sign. This was expected to be achieved by a three-dimensional ring structure resembling medieval mail armor. How-ever, this was considered difficult, as the ring mesh of millionths of a meter in size would have to be composed of three different components.

If you’re tired of robocalls you might want to consider one of Google’s Pixel phones. On Thursday, Google announced that its Call Screen feature, which automatically blocks known robocallers in Google’s database, is rolling out to all Pixel phones this week. It was previously only available on the newest Pixel 3 and Pixel 4 devices. (The original Pixel phone, which launched in 2016, stopped receiving software updates last year, but Google says it’ll still get Call Screen.)

Robocalls may be driving you nuts. According to the YouMail robocall index, which is compiled from the YouMail app that’s built to also block robocalls, there were 4.7 billion robocalls placed in the U.S. in January 2020, or 1,800 a second and 14.4 calls per person. Some U.S. carriers, like AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile and Sprint are working in the background to prevent robocalls, too. Though sometimes they still sneak through or only work on certain phones.

And other companies, like Apple, let you automatically send calls that are received from people who aren’t in your address book right to voicemail. But sometimes you miss an important call from someone, like a doctor whose number you might not have saved.

Facial recognition technology is likely not as safe as you may have thought. This was illustrated by a recent test where 3D printed busts of peoples’ heads were used to unlock smartphones.

Out of five tested phones, only one refused to open when presented with the fake head.

Other biometric security measures are also showing less resilience to hacking than you might expect. A group of Japanese researchers recently showed it was possible to copy a person’s fingerprints from pictures like the ones many of us post on social media.

What if an umbrella could charge your phone? By tweaking well-known principles, scientists have created a highly efficient generator that can pump out lots of renewable energy with just a bit of water.

One of the many ways scientists hope to improve the performance of today’s lithium batteries is by swapping out some of the liquid components for solid ones. Known as solid-state batteries, these experimental devices could greatly extend the life of electric vehicles and mobile devices by significantly upping the energy density packed inside. Scientists at MIT are now reporting an exciting advance toward this future, demonstrating a new type of solid-state battery architecture that overcomes some limitations of current designs.

In a regular lithium battery, a liquid electrolyte serves as the medium through which the lithium ions travel back and forth between the anode and cathode as the battery is charged and discharged. One problem is that this liquid is highly volatile and can sometimes result in battery fires, like those that plagued Samsung’s Galaxy Note 7 smartphone.

Replacing this liquid electrolyte for a solid material wouldn’t just make batteries safer and less prone to fires, it could also open up new possibilities for other key components of the battery. The anode in today’s lithium batteries is made from a mix of copper and graphite, but if it were made of pure lithium instead, it could break the “energy-density bottleneck of current Li-ion chemistry,” according to a recent study published in Trends in Chemistry.

Pre-historic times and ancient history are defined by the materials that were harnessed during that period.

We have the stone age, the bronze age, and the iron age.

Today is a little more complex, we live in the Space Age, the Nuclear Age, and the Information Age.

And now we are entering the Graphene Age, a material that will be so influential to our future, it should help define the period we live in.

Potential applications for Graphene include uses in medicine, electronics, light processing, sensor technology, environmental technology, and energy, which brings us to Samsung’s incredible battery technology!

Imagine a world where mobile devices and electric vehicles charge 5 times faster than they do today.

Cell phones, laptops, and tablets that fully charge in 12 minutes or electric cars that fully charge at home in only an hour.

Samsung will make this possible because, on November 28th, they announced the development of a battery made of graphene with charging speeds 5 times faster than standard lithium-ion batteries.

Before I talk about that, let’s quickly go over what Graphene is.

When you first hear about Graphene’s incredible properties, it sounds like a supernatural material out of a comic book.

But Graphene is real! And it is made out of Graphite, which is the crystallized form of carbon and is commonly found in pencils.

Graphene is a single atom thick structure of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice and is a million time thinner than a human hair.

Graphene is the strongest lightest material on Earth.

It is 200 times stronger than steel and as much as 6 times lighter.

It can stretch up to a quarter of its length but at the same time, it is the hardest material known, harder than a diamond.

Graphene can also conduct electricity faster than any known substance, 140 times faster than silicone.

And it conducts heat 10 times better than copper.

It was first theorized by Phillip Wallace in 1947 and attempts to grow graphene started in the 1970s but never produced results that could measure graphene experimentally.

Graphene is also the most impermeable material known, even Helium atoms can’t pass through graphene.

In 2004, University of Manchester scientists Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov successfully isolated one atom thick flakes of graphene for the first time by repeatedly separating fragments from chunks of graphite using tape, and they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010 for this discovery.

Over the past 10 years, the price of Graphene has dropped at a tremendous rate.

In 2008, Graphene was one of the most expensive materials on Earth, but production methods have been scaled up since then and companies are selling Graphene in large quantities.

Sources:

http://www.graphene.manchester.ac.uk/explore/the-story-of-gr…rly-years/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_graphene

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potential_applications_of_graphene

http://luratia.com/graphene/category/graphene-facts#sthash.3…mEmGp.dpbs

https://blogs.windows.com/devices/2013/02/07/hero-material-1…-graphene/

https://news.samsung.com/global/samsung-develops-battery-mat…ging-speed

O„.o.

The processor that makes your laptop or cell phone work was fabricated using quartz from this obscure Appalachian backwater.