Comes with improved math skills.

Read & tell me what you think 🙂

There is a rift between near and long-term perspectives on AI safety – one that has stirred controversy. Longtermists argue that we need to prioritise the well-being of people far into the future, perhaps at the expense of people alive today. But their critics have accused the Longtermists of obsessing on Terminator-style scenarios in concert with Big Tech to distract regulators from more pressing issues like data privacy. In this essay, Mark Bailey and Susan Schneider argue that we shouldn’t be fighting about the Terminator, we should be focusing on the harm to the mind itself – to our very freedom to think.

There has been a growing debate between near and long-term perspectives on AI safety – one that has stirred controversy. “Longtermists” have been accused of being co-opted by Big Tech and fixating on science fiction-like Terminator-style scenarios to distract regulators from the real, more near-term, issues, such as algorithmic bias and data privacy.

Longtermism is an ethical theory that requires us to consider the effects of today’s decisions on all of humanity’s potential futures. It can lead to extremes, as it concludes that one should sacrifice the present wellbeing of humanity for the good of humanity’s potential futures. Many Longtermists believe humans will ultimately lose control of AI, as it will become “superintelligent”, outthinking humans in every domain – social acumen, mathematical abilities, strategic thinking, and more.

The recent unprecedented success of foundation models like GPT-4 has heightened the general public’s awareness of artificial intelligence (AI) and inspired vivid discussion about its associated possibilities and threats. In March 2023, a group of technology leaders published an open letter that called for a public pause in AI development to allow time for the creation and implementation of shared safety protocols. Policymakers around the world have also responded to rapid advancements in AI technology with various regulatory efforts, including the European Union (EU) AI Act and the Hiroshima AI Process.

One of the current problems—and consequential dangers—of AI technology is its unreliability and subsequent lack of trustworthiness. In recent years, AI-based technologies have often encountered severe issues in terms of safety, security, privacy, and responsibility with respect to fairness and interpretability. Privacy violations, unfair decisions, unexplainable results, and accidents involving self-driving cars are all examples of concerning outcomes.

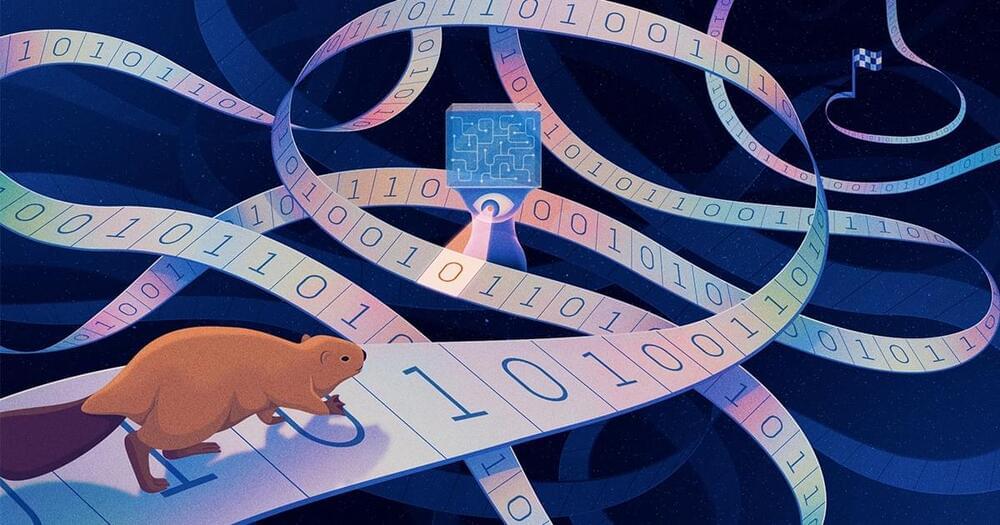

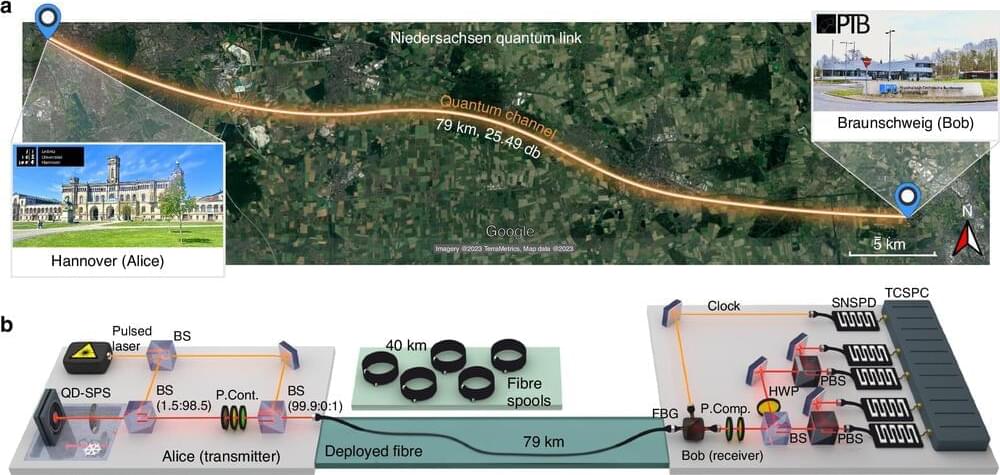

Conventional encryption methods rely on complex mathematical algorithms and the limits of current computing power. However, with the rise of quantum computers, these methods are becoming increasingly vulnerable, necessitating quantum key distribution (QKD).

QKD is a technology that leverages the unique properties of quantum physics to secure data transmission. This method has been continuously optimized over the years, but establishing large networks has been challenging due to the limitations of existing quantum light sources.

In a new article published in Light: Science & Applications, a team of scientists in Germany have achieved the first intercity QKD experiment with a deterministic single-photon source, revolutionizing how we protect our confidential information from cyber threats.

Number theorists have been trying to prove a conjecture about the distribution of prime numbers for more than 160 years.

The Riemann hypothesis is the most important open question in number theory—if not all of mathematics. It has occupied experts for more than 160 years. And the problem appeared both in mathematician David Hilbert’s groundbreaking speech from 1900 and among the “Millennium Problems” formulated a century later. The person who solves it will win a million-dollar prize.

This essay addresses Cartesian duality and how its implicit dialectic might be repaired using physics and information theory. Our agenda is to describe a key distinction in the physical sciences that may provide a foundation for the distinction between mind and matter, and between sentient and intentional systems. From this perspective, it becomes tenable to talk about the physics of sentience and ‘forces’ that underwrite our beliefs (in the sense of probability distributions represented by our internal states), which may ground our mental states and consciousness. We will refer to this view as Markovian monism, which entails two claims: fundamentally, there is only one type of thing and only one type of irreducible property (hence monism). All systems possessing a Markov blanket have properties that are relevant for understanding the mind and consciousness: if such systems have mental properties, then they have them partly by virtue of possessing a Markov blanket (hence Markovian). Markovian monism rests upon the information geometry of random dynamic systems. In brief, the information geometry induced in any system—whose internal states can be distinguished from external states—must acquire a dual aspect. This dual aspect concerns the (intrinsic) information geometry of the probabilistic evolution of internal states and a separate (extrinsic) information geometry of probabilistic beliefs about external states that are parameterised by internal states. We call these intrinsic (i.e., mechanical, or state-based) and extrinsic (i.e., Markovian, or belief-based) information geometries, respectively. Although these mathematical notions may sound complicated, they are fairly straightforward to handle, and may offer a means through which to frame the origins of consciousness.

Keywords: consciousness, information geometry, Markovian monism.

Ontic structural realism argues that structure is all there is. In (French, 2014) I argued for an ‘eliminativist’ version of this view, according to which the world should be conceived, metaphysically, as structure, and objects, at both the fundamental and ‘everyday’ levels, should be eliminated. This paper is a response to a number of profound concerns that have been raised, such as how we might distinguish between the kind of structure invoked by this view and mathematical structure in general, how we should choose between eliminativist ontic structural realism and alternative metaphysical accounts such as dispositionalism, and how we should capture, in metaphysical terms, the relationship between structures and particles. In developing my response I shall touch on a number of broad issues, including the applicability of mathematics, the nature of representation and the relationship between metaphysics and science in general.

Keywords: Causation; Dependence; Disposition; Metaphysics; Object; Representation; Structure.

Copyright © 2018. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Most of us are familiar with the classic example of a liquid-gas moving contact line on a solid surface: a raindrop, sheared by the wind, creeps along a glass windscreen. The contact line’s movements depend on the interplay between viscous and surface tension forces—a relationship that has been thoroughly investigated in experimental fluid mechanics.

In a study published in The European Physical Journal Special Topics, Harish Dixit, of the Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad, and his colleagues now examine the movements of a contact line formed at the interface between two immiscible liquids and a solid. The experiments fill a gap in fluid dynamics and suggest a mechanism for an imposed boundary condition that eludes mathematical description.

According to theory, the movement of a liquid-liquid contact line should be governed entirely by the liquids’ viscosity ratio and the angle at which the liquid interface meets the solid. To examine this in a real-world system, Dixit and his colleagues filled a rectangular tank with two liquid layers—silicone oil atop sugar water—with similar densities but significantly different viscosities. The researchers placed a glass slide at the edge of the tank, which they could slide vertically to create a moving contact line.