Electrocaloric (EC) cooling works by using electricity to generate a cooling effect, which is more efficient, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly compared to traditional vapor-compression-based cooling methods.

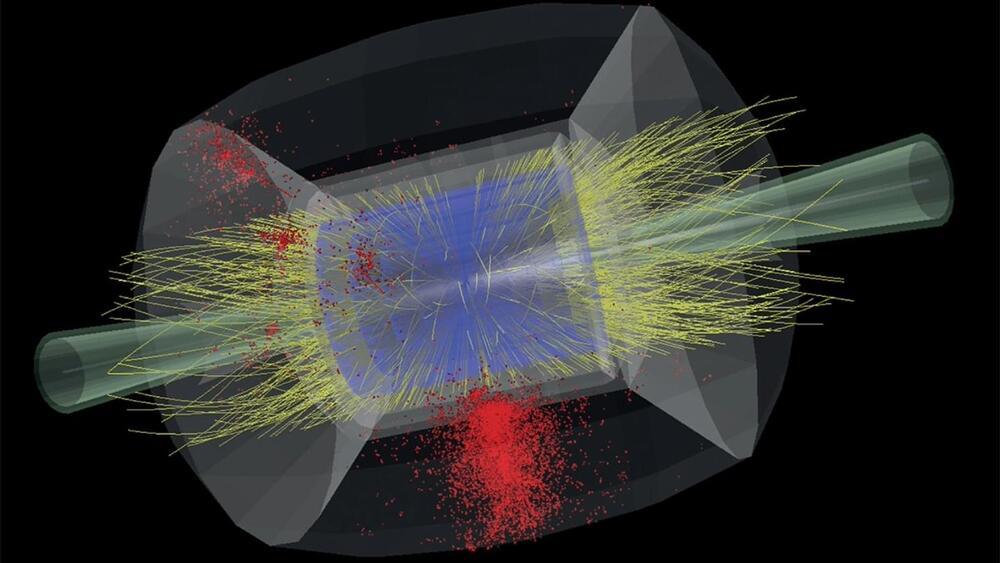

Now, scientists have not only cooled muons but also accelerated them in an experiment at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex, or J-PARC, in Tokai. The muons reached a speed of about 4 percent the speed of light, or roughly 12,000 kilometers per second, researchers report October 15 at arXiv.org.

The scientists first sent the muons into an aerogel, a lightweight material that slowed the muons and created muonium, an atomlike combination of a positively charged muon and a negatively charged electron. Next, a laser stripped away the electrons, leaving behind cooled muons that electromagnetic fields then accelerated.

Muon colliders could generate higher energy collisions than machines that smash protons, which are themselves made up of smaller particles called quarks. Each proton’s energy is divvied up among its quarks, meaning only part of the energy goes into the collision. Muons have no smaller bits inside. And they’re preferable to electrons, which lose energy as they circle an accelerator. Muons aren’t as affected by that issue thanks to their larger mass.

An international research team has for the first time designed realistic photonic time crystals–exotic materials that exponentially amplify light. The breakthrough opens up exciting possibilities across fields such as communication, imaging and sensing by laying the foundations for faster and more compact lasers, sensors and other optical devices.

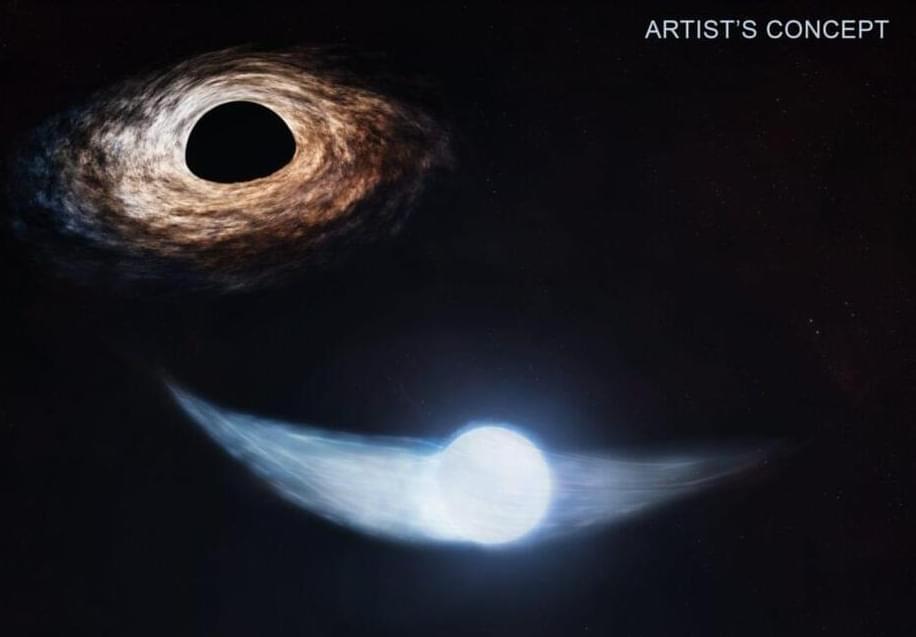

A black hole in the MAXI J1820+070 system ejected about 400 million billion pounds of gas in twin jets—equivalent to 500 million times the mass of the Empire State Building.

In a significant astronomical discovery, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory captured a rare phenomenon: a black hole ejecting massive jets of material at nearly the speed of light. This black hole is part of the binary system MAXI J1820+070, positioned approximately 10,000 light-years away, which is relatively close in cosmic terms. This proximity allowed detailed observations that contribute to our understanding of how black holes interact with companion stars.

The MAXI J1820+070 system features a black hole about eight times the mass of the sun, drawing material from a companion star roughly half the sun’s mass. This process creates an accretion disk—a luminous sphere emitting bright X-rays as material is funneled toward the black hole. While some gas is absorbed, some is expelled in powerful jets that travel in opposite directions.

Polyethylene (PE) is one of the most widely used and versatile plastic materials globally, prized for its cost-effectiveness, lightweight properties and ease of formability. These characteristics make PE indispensable across a broad spectrum of applications, from packaging materials to structural plastics.

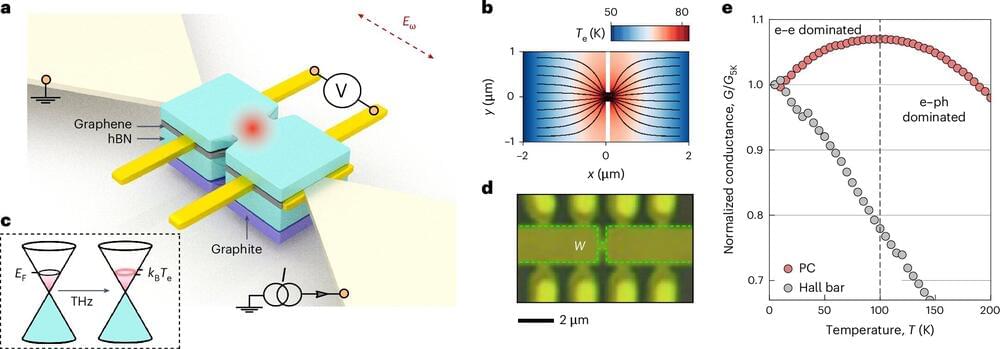

When light hits the surface of some materials, namely those exhibiting a property known as photoresistance, it can induce changes in their electrical conductivity. Graphene is among these materials, as incident light can excite electrons within it, affecting its photoconductivity.

Researchers at the National University of Singapore report a deviation from standard photoresistive behaviors in doped metallic graphene. Their paper, published in Nature Nanotechnology, shows that when exposed to continuous-wave terahertz (THz) radiation, Dirac electrons in this material can be thermally decoupled from the lattice, prompting their hydrodynamic transport.

“Our research has emerged from the growing recognition that traditional models of electron behavior don’t fully capture the properties of certain advanced materials, particularly in the quantum world,” Denis Bandurin, Assistant Professor at NUS, lead of the experimental condensed matter physics lab and senior author of the paper, told Tech Xplore.

A breakthrough discovery in indium selenide could revolutionize memory storage technology by enabling crystalline-to-glass transitions with minimal energy.

Researchers found that this transformation can occur through mechanical shocks induced by continuous electric current, bypassing the energy-intensive melting and quenching process. This new approach reduces energy consumption by a billion times, potentially enabling more efficient data storage devices.

Revolutionary discovery in memory storage materials.

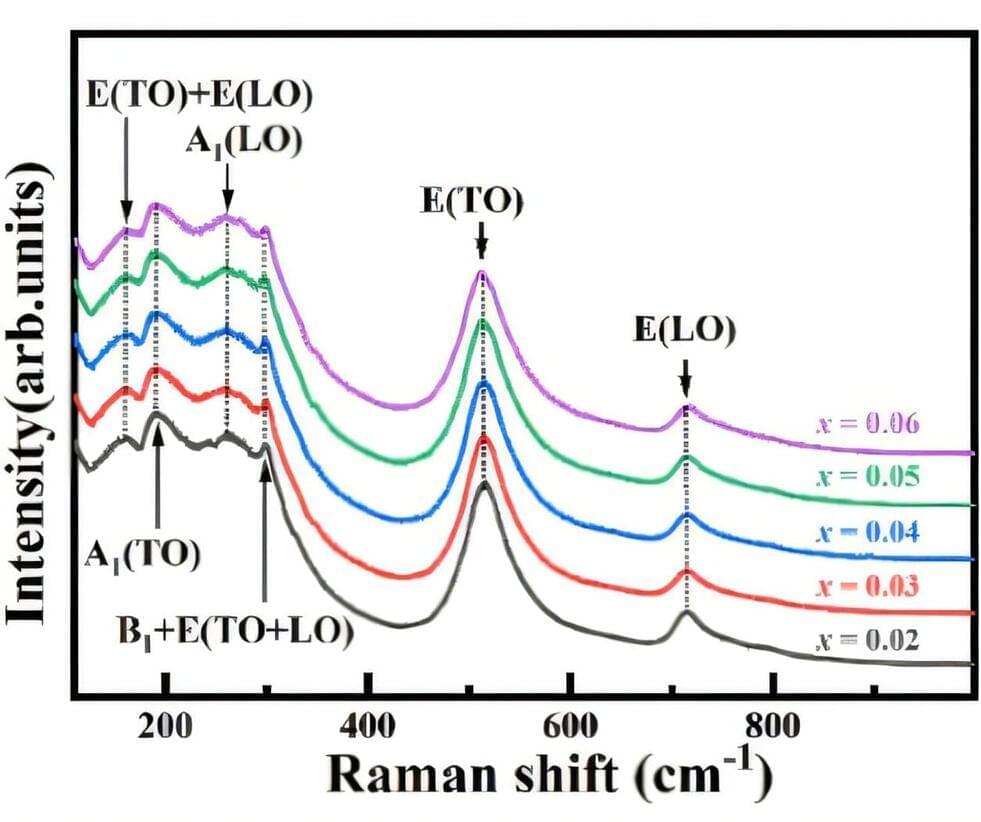

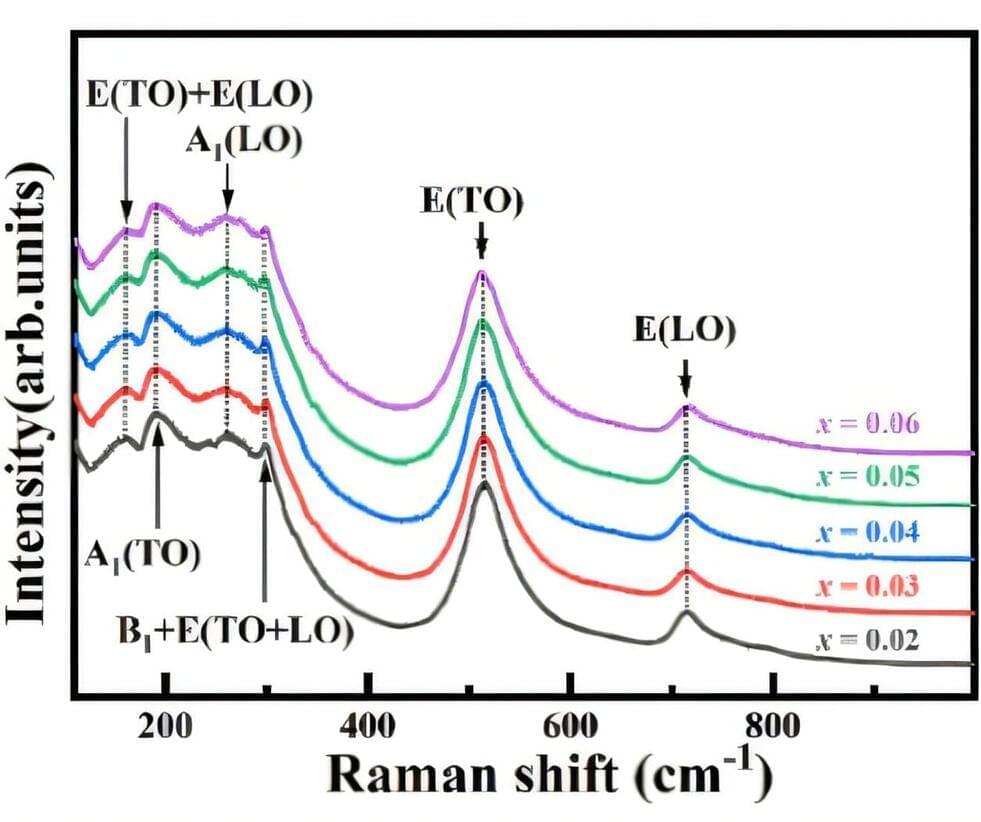

Minnesota researchers boost semiconductor transparency and speed for high-power devices.

A team of researchers at the University of Minnesota has developed a next-generation transparent and efficient semiconductor material. This breakthrough could have enormous ramifications for improving the efficiency of high-power electronics, especially those that need transparency, like lasers.

The material is entirely manmade, allowing electrons to travel faster while remaining transparent to visible and ultraviolet light.

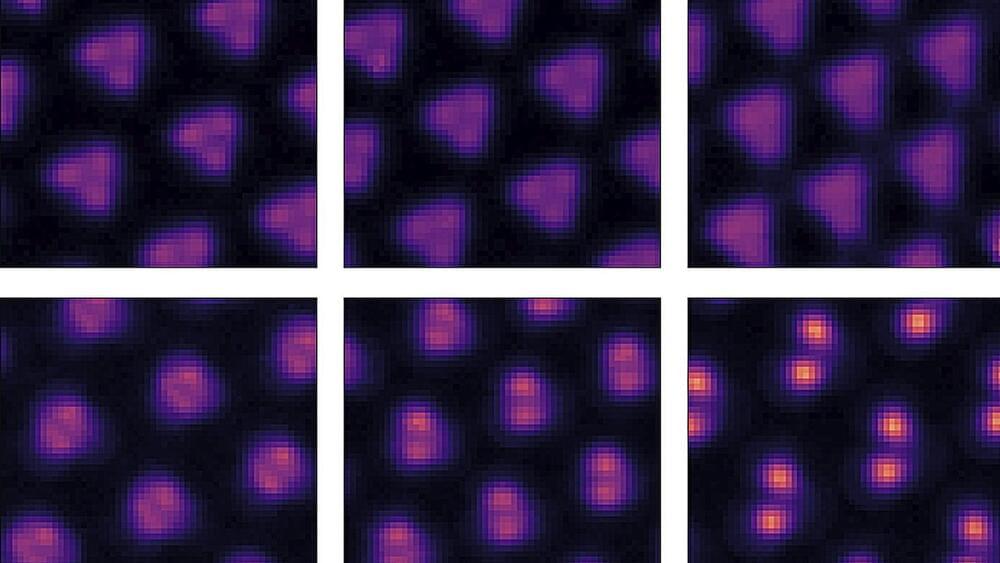

A small twist allowed scientists to capture a rare quantum phase that has been under the shadows for decades.

“Wigner molecular crystals are important because they may exhibit novel transport and spin properties that could be useful for future quantum technologies such as quantum simulations,” researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBL) note.

For the first time, LBL researchers have captured direct images of the Wigner molecular crystal using scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) —- an imaging technique that produces high-resolution visuals of materials at the atomic scale.

“We are the first to directly observe this new quantum phase, which was quite unexpected. It’s pretty exciting,” said Feng Wang, one of the study authors and a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Until now, only a small fraction of meteorites that land on Earth had been firmly linked back to their parent body out in space – but a set of new studies has just given us compelling origin stories for more than 90 percent of meteorites today.

Past analyses of meteorites striking our planet today suggest some kind of shared origin; they’re made from very similar materials and have been baked by cosmic radiation for a suspiciously short amount of time, hinting at a relatively recent break-up from shared parent bodies.

The teams behind three new published papers used a combination of super-detailed telescope observations and computer modeling simulations to compare asteroids out in space with meteorites recovered on Earth, matching up rock types and orbital paths between the two.