Researchers at Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and University of Ottawa found that high risk of obstructive sleep apnea was associated with approximately 40% higher odds of a composite poor mental health outcome at baseline and follow-up among adults aged 45–85 years in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging.

Identifying factors associated with mental health outcomes is an important goal on several fronts. Mental health conditions rank among the leading contributors to global disease burden, with anxiety and depressive disorders described as most common. Individuals living with mental health conditions face higher risks of cardiometabolic diseases, unemployment, homelessness, disability, and hospitalizations. Economically, mental disorders carry an estimated $1 trillion annual global cost in lost productivity.

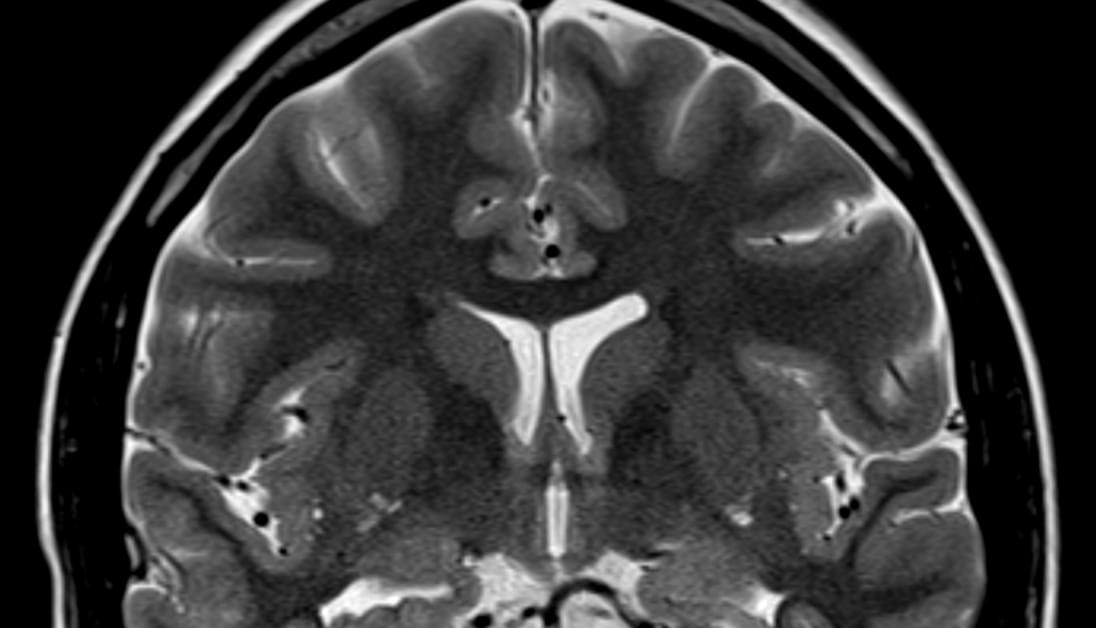

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) involves repeated upper airway narrowing during sleep. Disturbed breathing can break up sleep (sleep fragmentation), trigger a stress response in the nervous system (sympathetic activation), and cause episodes of low oxygen in the blood (intermittent hypoxemia).