An analysis of ongoing trials suggests that mRNA cancer vaccines have the potential to deliver health benefits worth $75 billion each year in the US alone

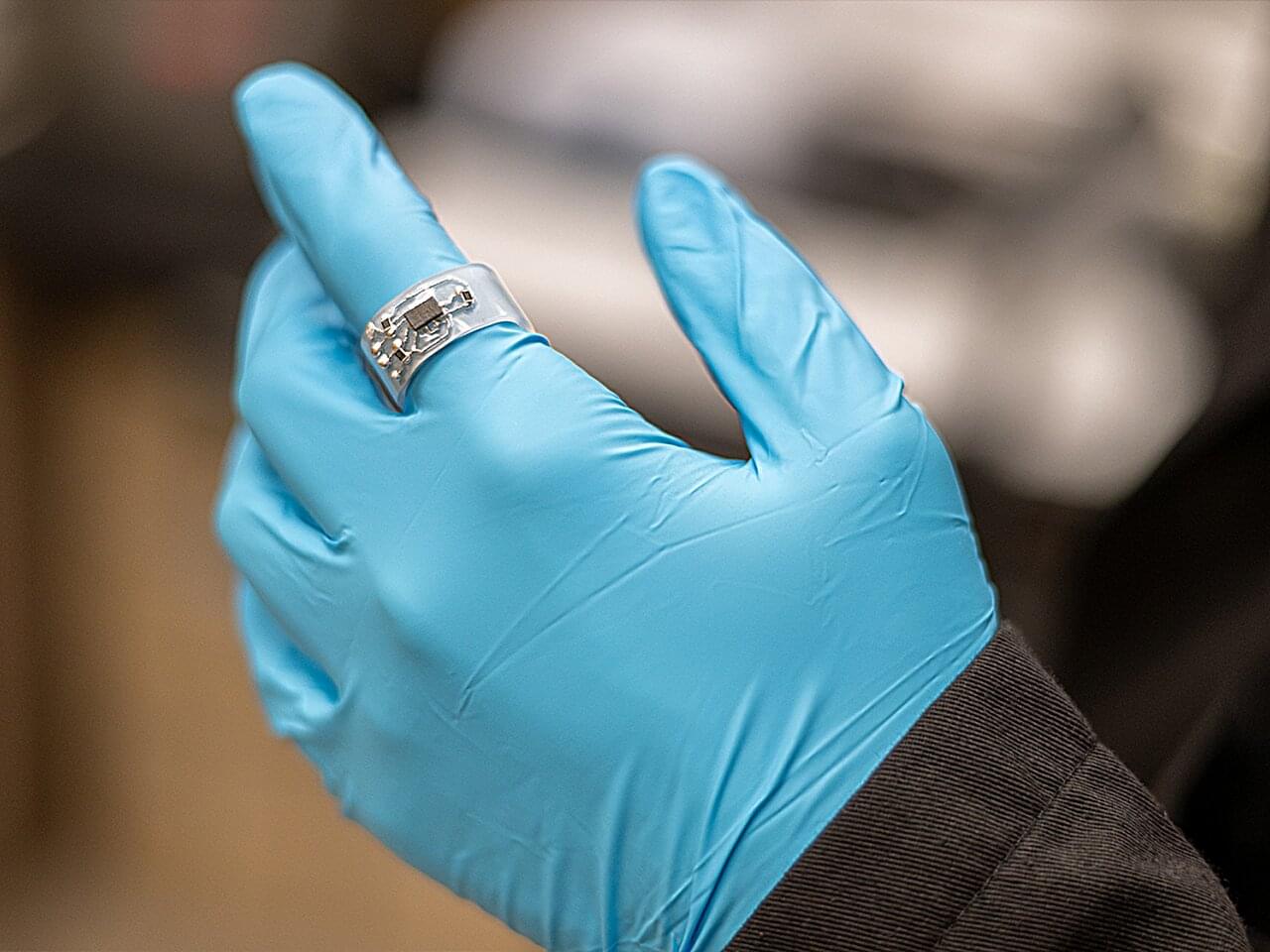

Wearable electronics could be more wearable, according to a research team at Penn State. The researchers have developed a scalable, versatile approach to designing and fabricating wireless, internet-enabled electronic systems that can better adapt to 3D surfaces, like the human body or common household items, paving the path for more precise health monitoring or household automation, such as a smart recliner that can monitor and correct poor sitting habits to improve circulation and prevent long-term problems.

The method, detailed in Science Advances, involves printing liquid metal patterns onto heat-shrinkable polymer substrates—otherwise known as the common childhood craft “Shrinky Dinks.” According to team lead Huanyu “Larry” Cheng, James L. Henderson, Jr. Memorial Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics in the College of Engineering, the potentially low-cost way to create customizable, shape-conforming electronics that can connect to the internet could make the broad applications of such devices more accessible.

“We see significant potential for this approach in biomedical uses or wearable technologies,” Cheng said, noting that the field is projected to reach $186.14 billion by 2030. “However, one significant barrier for the sector is finding a way to manufacture an easy-to-customize device that can be applied to freestanding, freeform surfaces and communicate wirelessly. Our method solves that.”

Immune cells work to fight infection and other diseases. Different subsets work together to elicit a healthy immune response; however, infections and disease can dysregulate cells and prevent effective immunity. Interestingly, cancer can use immune cells to its advantage.

Cancer employs various mechanisms to alter the immune system. Once established, tumor cells secrete proteins and molecules to generate a favorable environment. In this case, the tumor microenvironment (TME) becomes hypoxic due to a lack of oxygen with increased blood vessel growth to bring nutrients to the tumor and altered cell types that promote tumor progression. Specifically, tumor-secreted molecules polarize healthy immune cells, which allow cancer cells to proliferate and travel to distal tissues of the body.

T cells are specific immune cells responsible for identifying and targeting pathogens. Receptors on T cells recognize proteins on the surface of infected cells, which stimulate an immune response that eliminates the disease. These cells are critical for effective health and many immunotherapies aim to amplify or enhance T cell function. In the context of cancer, these T cells lose their function and, in some cases, promote tumor growth by inhibiting other immune cells. Unfortunately, treatment efficacy is limited to specific subsets of patients due to tumor type and stage of disease. Scientists are currently working to understand more about T cell biology and enhance immunotherapy.

The 2026 Timeline: AGI Arrival, Safety Concerns, Robotaxi Fleets & Hyperscaler Timelines ## The rapid advancement of AI and related technologies is expected to bring about a transformative turning point in human history by 2026, making traditional measures of economic growth, such as GDP, obsolete and requiring new metrics to track progress ## ## Questions to inspire discussion.

Measuring and Defining AGI

🤖 Q: How should we rigorously define and measure AGI capabilities? A: Use benchmarks to quantify specific capabilities rather than debating terminology, enabling clear communication about what AGI can actually do across multiple domains like marine biology, accounting, and art simultaneously.

🧠 Q: What makes AGI fundamentally different from human intelligence? A: AGI represents a complementary, orthogonal form of intelligence to human intelligence, not replicative, with potential to find cross-domain insights by combining expertise across fields humans typically can’t master simultaneously.

📊 Q: How can we measure AI self-awareness and moral status? A: Apply personhood benchmarks that quantify AI models’ self-awareness and requirements for moral treatment, with Opus 4.5 currently being state-of-the-art on these metrics for rigorous comparison across models.

AI Capabilities and Risks.

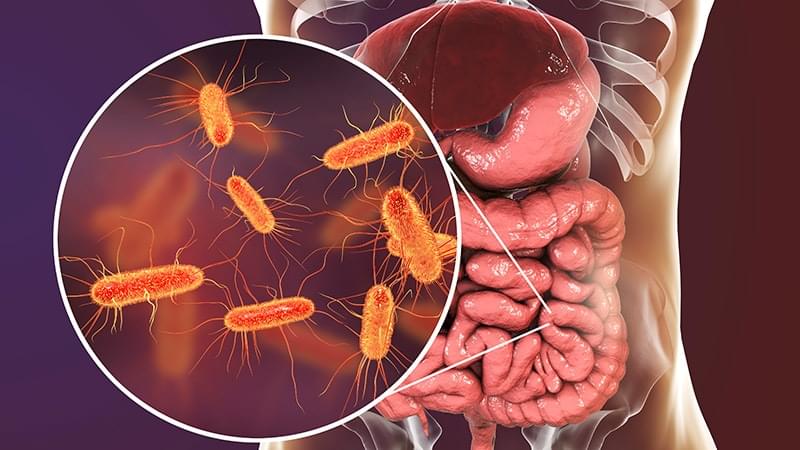

Periodontitis is widespread and can have serious consequences for overall health. Researchers at Fraunhofer have identified a substance that selectively inhibits only those bacteria that cause periodontitis, thereby preserving the natural balance of the oral microbiome. This technology has been further developed and commercialized as a range of oral care products by the spin-off company PerioTrap.

The oral microbiome is home to more than 700 different bacterial species, of which only a few can cause periodontitis. These adhere to dental plaque, particularly along the gum line, where they trigger inflammation (gingivitis). This can potentially lead to chronic periodontitis, which does more than just cause receding gums and loose teeth. If these bacteria enter the bloodstream, they can also contribute to the development of diabetes, rheumatic disease, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammatory bowel disease and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Pathogenic bacteria are killed by conventional oral care products such as alcohol-based mouthwashes and products containing the antiseptic chlorhexidine, but these also eliminate beneficial microorganisms. When the oral microbiome re-establishes itself after treatment, pathogenic bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis gain an early advantage because they proliferate particularly well in inflamed gum tissue. Beneficial bacteria grow more slowly, and the oral microbiome quickly shifts back from its natural balance into dysbiosis, allowing the disease to recur.

For the first time, researchers at UBC have demonstrated how to reliably produce an important type of human immune cell — known as helper T cells — from stem cells in a controlled laboratory setting. The findings, published today in Cell Stem Cell, overcome a major hurdle that has limited the development, affordability and large-scale manufacturing of cell therapies. The discovery could pave the way for more accessible and effective off-the-shelf treatments for a wide range of conditions like cancer, infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders and more.

“This is a major step forward in our ability to develop scalable and affordable immune cell therapies.”

Dr. Peter Zandstra

Ranked among the world’s top medical schools with the fifth-largest MD enrollment in North America, the UBC Faculty of Medicine is a leader in both the science and the practice of medicine. Across British Columbia, more than 12,000 faculty and staff are training the next generation of doctors and health care professionals, making remarkable discoveries, and helping to create the pathways to better health for our communities at home and around the world.

“This moves the conversation beyond anecdotes and self-reports to real-world behavior,” said Dr. Jason Nagata.

How much time during school hours do teens spend on social media? This is what a recent study published in JAMA hopes to address as a team of researchers investigated connections between adolescent phone use during school. This study has the potential to help researchers, academic administrators, students, and parents become aware of the connections between adolescent phone use and all-around health.

For the study, the researchers analyzed data regarding smartphone app usage during school hours from 640 adolescents aged 13–18 through software installed on their phones that was approved by all participants and their parents. The goal of the study was to ascertain phone app usage during school hours, with data being obtained from September 2022 to May 2024. In the end, the researchers found that teens spent about 1.16 hours each school day on smartphones, mostly using social media apps, with higher use among older students and those from underprivileged households.