When skeletal defects are unable to heal on their own, bone tissue engineering (BTE), a developing field in orthopedics can combine materials science, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine to facilitate bone repair. Materials scientists aim to engineer an ideal biomaterial that can mimic natural bone with cost-effective manufacturing techniques to provide a framework that offers support and biodegrades as new bone forms. Since applications in BTE to restore large bone defects are yet to cross over from the laboratory bench to clinical practice, the field is active with burgeoning research efforts and pioneering technology.

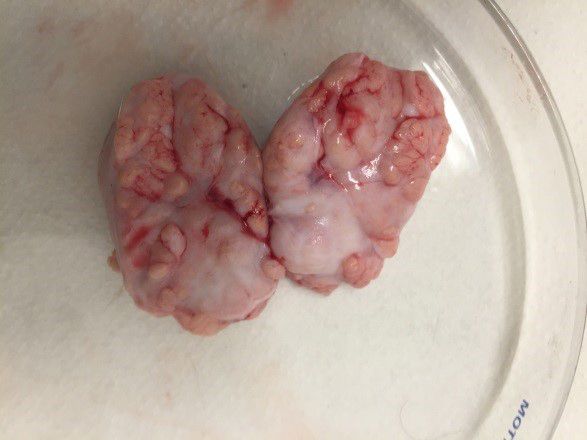

Cost-effective three-dimensional (3D) printing (additive manufacturing) combines economical techniques to create scaffolds with bioinks. Bioengineers at the Pennsylvania State University recently developed a composite ink made of three materials to 3D print porous, bone-like constructs. The core materials, polycaprolactone (PCL) and poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolide) acid (PLGA), are two of the most commonly used synthetic, biocompatible biomaterials in BTE. Now published in the Journal of Materials Research, the materials showed biologically favorable interactions in the laboratory, followed by positive outcomes of bone regeneration in an animal model in vivo.

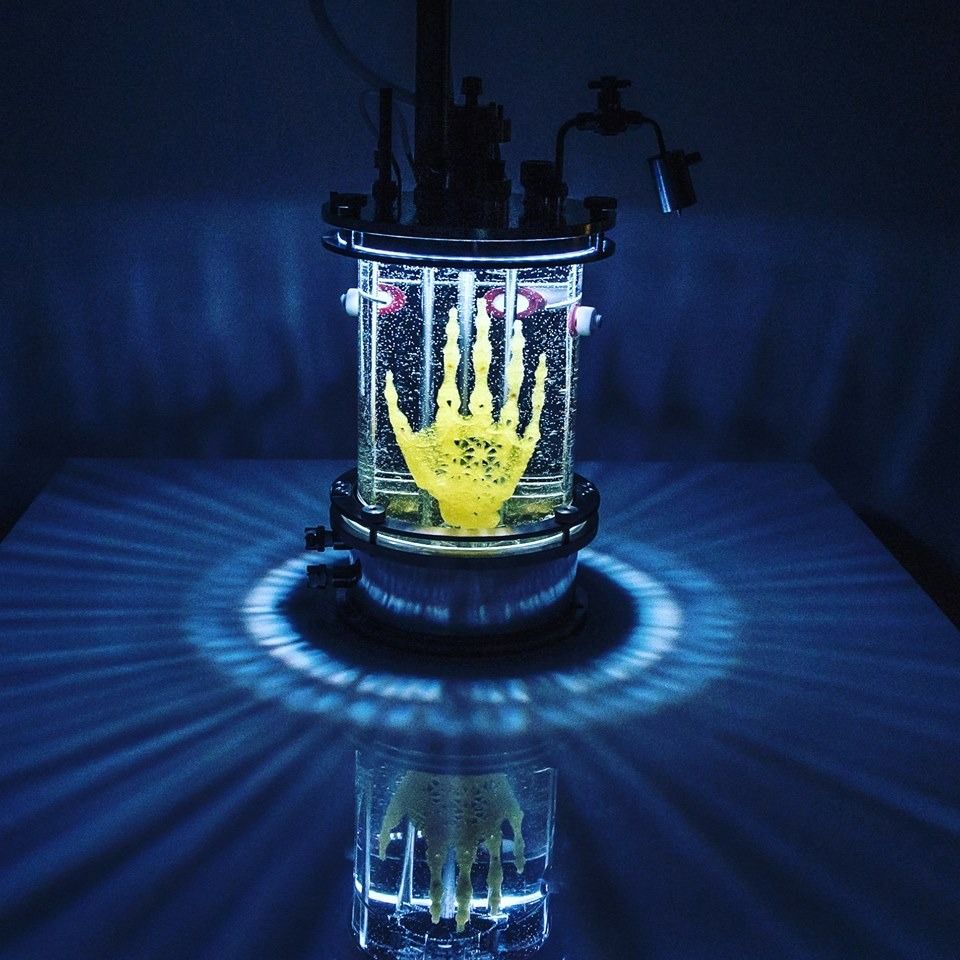

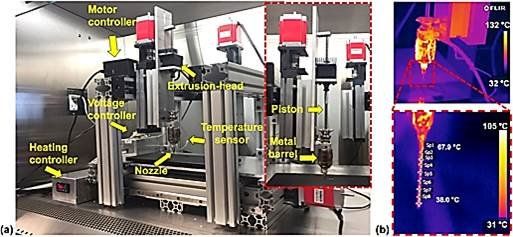

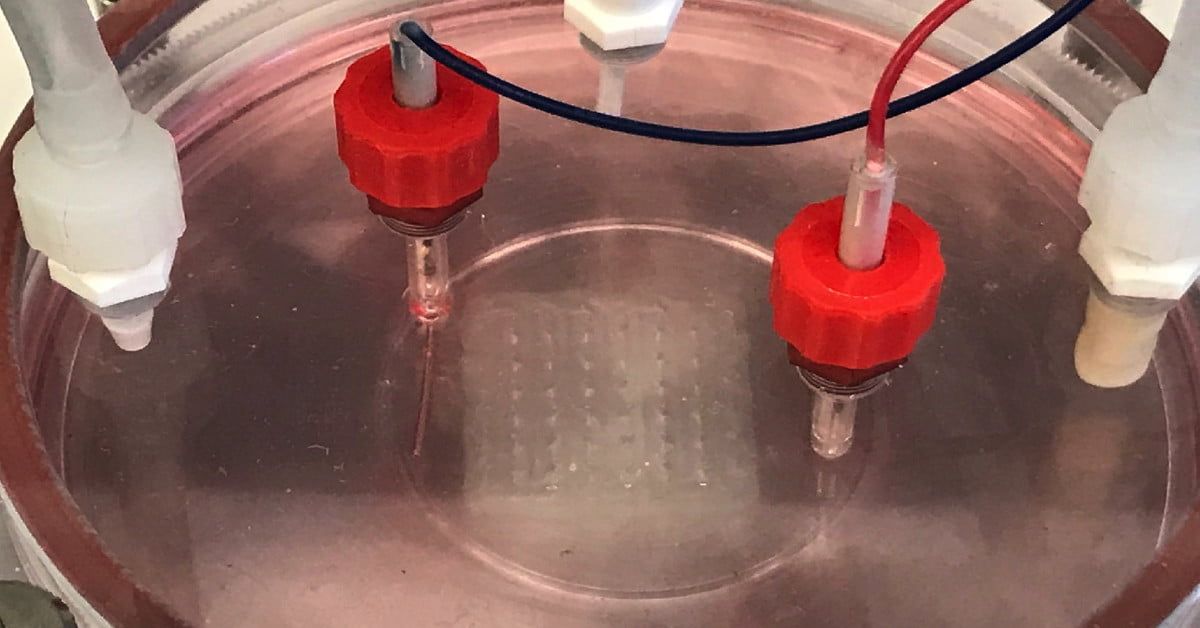

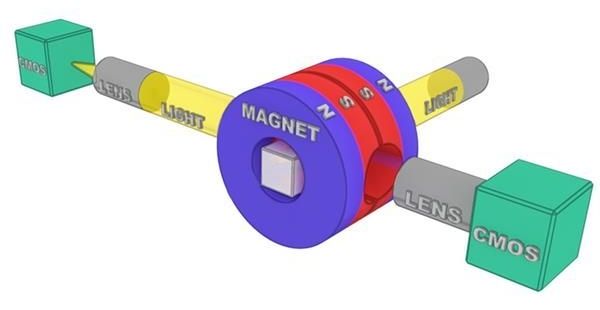

Since bone is a complex structure, Moncal et al. developed a bioink made of biocompatible PCL, PLGA and hydroxyapatite (HAps) particles, combining the properties of bone-like mechanical strength, biodegradation and guided reparative growth (osteoconduction) for assisted natural bone repair. They then engineered a new custom-designed mechanical extrusion system, which was mounted on the Multi-Arm Bioprinter (MABP), previously developed by the same group, to manufacture the 3D constructs.