Using the characteristic movement pattern of microbes to detect them on mars and the icy moons.

Microbial Motility.

The dissemination of synthetic biology into materials science is creating an evolving class of functional, engineered living materials that can grow, sense and adapt similar to biological organisms.

Nature has long served as inspiration for the design of materials with improved properties and advanced functionalities. Nonetheless, thus far, no synthetic material has been able to fully recapitulate the complexity of living materials. Living organisms are unique due to their multifunctionality and ability to grow, self-repair, sense and adapt to the environment in an autonomous and sustainable manner. The field of engineered living materials capitalizes on these features to create biological materials with programmable functionalities using engineering tools borrowed from synthetic biology. In this focus issue we feature a Perspective and an Article to highlight how synergies between synthetic biology and biomaterial sciences are providing next-generation engineered living materials with tailored functionalities.

Innovations in computing tech have improved the accuracy of DNA synthesis and enabled synthetic biology to work in the real world.

I don’t know about you, but I’m constantly looking for the “next big thing” in the stock market. And I think synthetic biology might just be it.

Why? If you invested just $10,000 into any of those world-changing stocks back in their early days, you’d have MILLIONS today. Forget the Iraq War, the housing crash, the European debt crisis. Forget the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. Through it all, you’d have millions today.

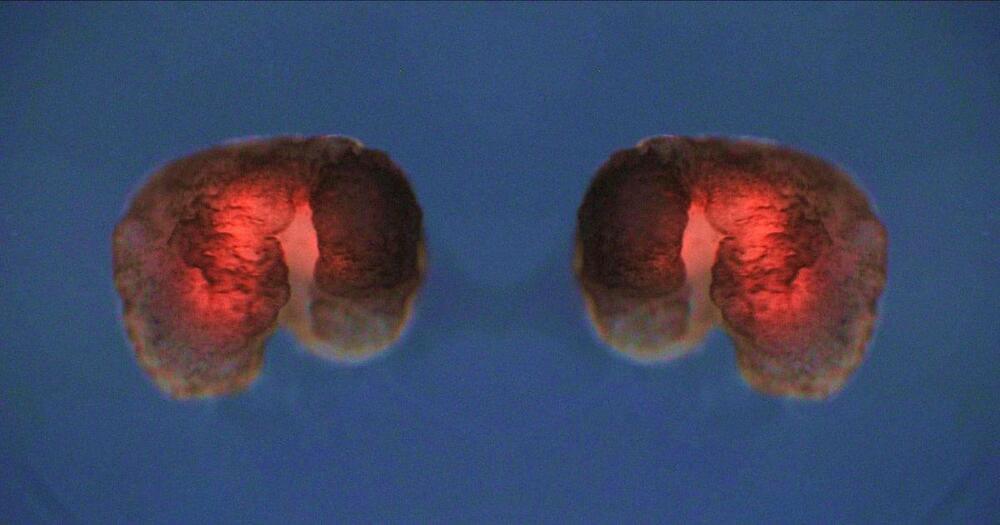

Scientists have created synthetic organisms that can self-replicate. Known as “Xenobots,” these tiny millimeter-wide biological machines now have the ability to reproduce — a striking leap forward in synthetic biology.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 0, a joint team from the University of Vermont, Tufts University, and Harvard University used Xenopus laevis frog embryonic cells to construct the Xenobots.

Their original work began in 2020 when the Xenobots were first “built.” The team designed an algorithm that assembled countless cells together to construct various biological machines, eventually settling on embryonic skin cells from frogs.

Scientists at Northwestern Medicine are using new advances in CRISPR gene-editing technology to uncover new biology that could lead to longer-lasting treatments and new therapeutic strategies for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

The HIV epidemic has been overlooked during the COVID-19 pandemic but represents a critical and ongoing threat to human health with an estimated 1.5 million new infections in the last year alone.

Drug developers and research teams have been searching for cures and new treatment modalities for HIV for over 40 years but are limited by their understanding of how the virus establishes infection in the human body. How does this small, unassuming virus with only 12 proteins—and a genome only a third of the size of SARS-CoV-2—hijack the body’s cells to replicate and spread across systems?

Mar 31, 2022

Our 91st episode with a summary and discussion of last week’s big AI news!

Outline:

Applications & Business.

Meet the DeepMind mafia: These 18 alumni from Google’s AI research lab are raising millions for their own startups, from climate to crypto.

Nvidia unveils new technology to speed up AI, launches new supercomputer.

Computer scientists at the University of California San Diego are showing how soil microbes can be harnessed to fuel low-power sensors. This opens new possibilities for microbial fuel cells (MFCs), which can power soil hydration sensors and other devices.

Led by Department of Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) Assistant Professor Pat Pannuto and Gabriel Marcano, a Ph.D. student working with Pannuto, this research was presented today at the first Association for Computer Machinery (ACM) Workshop on No Power and Low Power Internet of Things.

“Our most immediate applications are in agricultural settings, trying to create closed-loop controls. First for watering, but eventually for fertilization and treatment: sensing nitrates, nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium. This could help us understand how to limit run off and other effects,” said Pannuto, senior author on the study titled “Soil Power? Can Microbial Fuel Cells Power Non-Trivial Sensors?”

In biology, symmetry is typically the rule rather than the exception. Our bodies have left and right halves, starfish radiate from a central point and even trees, though not largely symmetrical, still produce symmetrical flowers. In fact, asymmetry in biology seems quite rare by comparison.

Does this mean that evolution has a preference for symmetry? In a new study, an international group of researchers, led by Iain Johnston, a professor in the Department of Mathematics at the University of Bergen in Norway, says it does.

Which, to me, sounds both unimaginably complex and sublimely simple.

Sort of like, perhaps, like our brains.

Building chips with analogs of biological neurons and dendrites and neural networks like our brains is also key to the massive efficiency gains Rain Neuromorphics is claiming: 1,000 times more efficient than existing digital chips from companies like Nvidia.