One million years ago. An ancient hominid cradles a large stone—black and glassy—in the palm of his hand, feeling for creases in the rock with his fingertips. In the other hand he grasps the antler of a deer, the bone’s blunt base pointing forward. He strikes the stone with the antler, and it splits along an invisible fracture. He flips it over and strikes again. Another flake of stone falls away. Examining the contours of the rock he continues to flip and strike—sometimes with force, other times with a gentle tap. Gradually, a useful and deadly object emerges from the formless stone. It is a bifaced handaxe, the most important tool that accompanied our ancestors out of Africa.

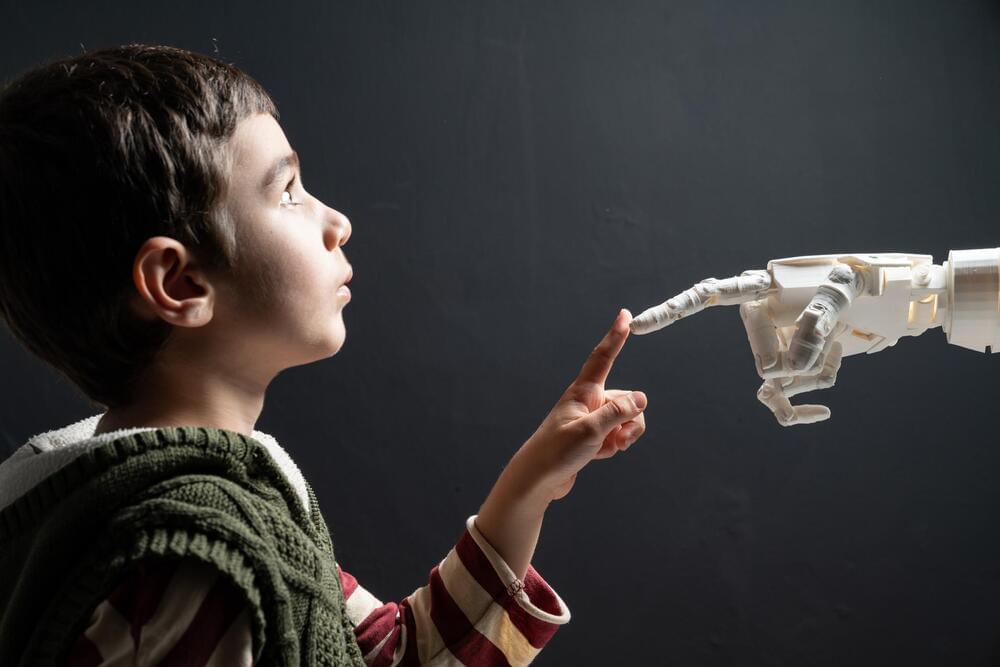

Movies and television usually depict embodied AI as a malevolent robot. Terror sells. But without access to the physical world and a tactile curiosity, AI will never be fully creative.