Increased inter-brain synchrony has been linked with social closeness (Kinreich et al., 2017), rapport (Nozawa et al., 2019), agreement (Richard et al., 2021), sense of joint agency (Shiraishi and Shimada, 2021), prosociality (Hu et al., 2017), similarity of flow states (Nozawa et al., 2021), shared meaning-making (Stolk et al., 2014), and cooperation (Cui et al., 2012; Toppi et al., 2016; Szymanski et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2019). Phase-coupled brain stimulation has led to increased interpersonal synchrony (Novembre et al., 2017), as well as improved interpersonal learning (Pan et al., 2020b). Furthermore, preceding a learning task with synchronized physical activity led to both better rapport and increased inter-brain synchrony, although task performance was unaffected (Nozawa et al., 2019). Nonetheless, learning outcomes (Pan et al., 2020a) and team performance in a variety of tasks (Szymanski et al., 2017; Reinero et al., 2020) can be predicted with the amount of inter-brain synchrony occurring between interacting individuals. Even though collaboration is a dynamic phenomenon, previous studies reporting connections between positive social outcomes and inter-brain synchronization have not explored the temporal aspects of this phenomenon, as recently pointed out by Li et al. (2021). Their fNIRS study revealed differences in the time courses of inter-brain synchronization during two different cooperative tasks. The connection between temporal changes in inter-brain synchronization and the success of collaboration is, however, still not clear.

EEG and fNIRS allow freer movement and more natural interaction compared to magnetic imaging such as fMRI and MEG, arguably lending themselves most easily to actual interactive situations. However, interpersonal synchronization and mirroring between people engaged in social interaction involve quite fast timing precision. For example, participants’ movements were synchronized to less than 40 ms in the mirror game, in which participants improvise motion together (Noy et al., 2011). As EEG measures the electrical activity of the brain, it represents a faster changing signal than hemodynamic measurement, i.e. measures of blood flow, such as fNIRS. This makes EEG a suitable method for investigating fast changes in phase synchronization of oscillatory activity during dynamic social interaction, when taking into account the limitations of the method in regards to signal-to-noise ratio.

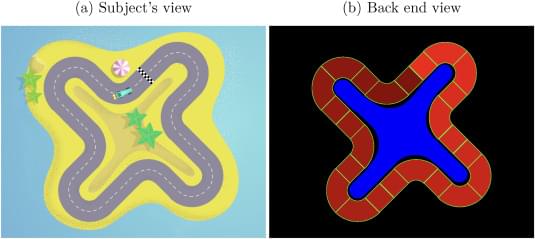

In this study, we wanted to investigate whether cooperative action of physically isolated participants would lead to inter-brain phase synchronization. We were especially interested in the temporal dynamics of inter-brain synchrony and its connection to performance in a collaborative task. We attempted to create an experimental setup which would facilitate the occurrence of inter-brain synchrony, while removing any bodily cues and controlling, as much as possible, for spurious synchronization. We also wanted to create a granular performance measure that could be calculated for any segment of the data, to make it possible to investigate dynamic changes in synchrony during the measurement and their connection to dynamic changes in collaborative success during the task.