The team plans to keep studying whether vaccines could help alleviate IBD symptoms, which tend to stay dormant then flare up. They also hope to find similar ways to nudge a dysfunctional gut microbiome back into balance.

The connection between gut bacteria and our overall health has been well studied in recent years. And while many of the specifics of this relationship are still unknown, it’s clear that a balanced microbiome with the right mix of bacteria helps maintain many of our regular bodily functions; conversely, the wrong mix of bacteria might help cause or signal the emergence of illness. But bacteria are only one type of microbe, and there’s been less work studying the many viruses and fungi that inhabit our body.

This new research was conducted by scientists from the University of Utah Health, who were curious if fungi were relevant to the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s. IBD is a complicated disorder, thought to have several contributing factors, including genetics. But recent research has suggested that certain species of fungi and yeast (the single celled version of fungi) could be one of these risk factors, including a common fungi in our gut called Candida albicans.

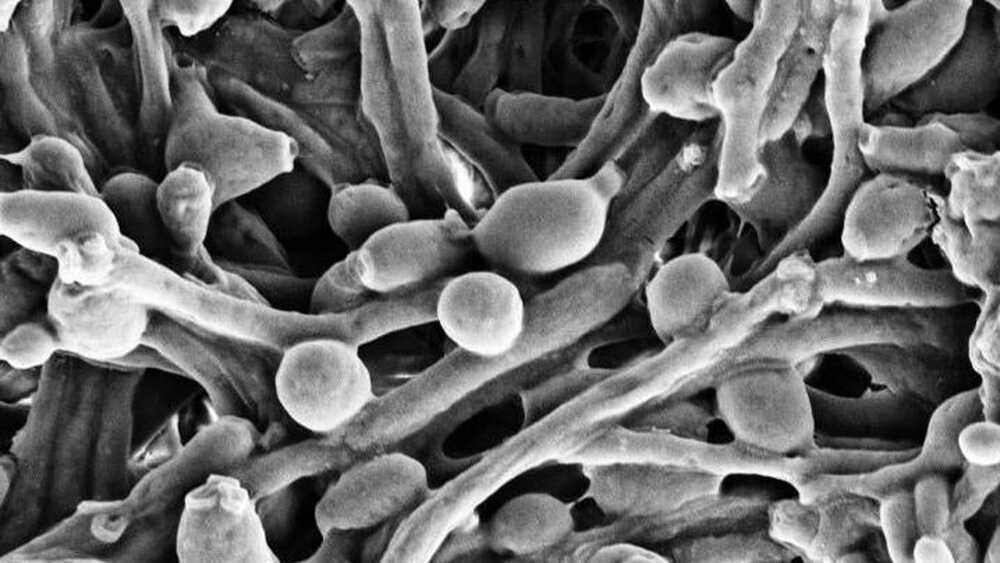

In experiments with mice, the team noticed that a functioning immune system seemed to interact with C. albicans. The yeast has the uncanny ability to switch between different forms of growth. It can remain a ball-like single-celled organism, or it can turn into a multicellular form, decked out with hyphae, a common branch-like structure found in most other fungi, that allows it to invade the tissues of our body to keep growing. The team found evidence that antibodies specific to C. albicans didn’t outright try to kill it—instead, they kept the yeast from turning into this more invasive form. But once the yeast was allowed to grow unfettered, the mice became sick with IBD-like symptoms, which can include diarrhea, intense cramps, and weight loss.