There’s a lot of water to work with.

Daimler, Mercedes-Benz’s parent company, announced last week a $1 billion investment in electric car and battery production in the US.

As with any new EV investment from a legacy automaker, the media painted it as an “attack on Tesla”, but Elon Musk, Tesla’s CEO and largest shareholder, doesn’t seem too worried about it.

Gogoro, which wants to redefine urban transportation to make it more sustainable, announced today that it has raised a whopping $300 million to further its mission. New investors Temasek, Al Gore’s Generation Investment Management, Sumitomo Corporation, and ENGIE joined existing investors Dr. Samuel Yin, founder of the Tang Prize and chairman of Ruentex Group; Panasonic; and others.

Based in Taipei, Taiwan, Gogoro developed a cloud-powered battery-swapping network called the Gogoro Energy Network. The aim, according to cofounder and CEO Horace Luke, is to build an infrastructure model to power electric mobility.

“The smart connected infrastructure focuses on optimizing the Gogoro Energy Network to make sure that customers always have access to charged batteries,” Luke said in an interview with VentureBeat.

This is how you really get an industry to change its ways. Bloomberg reports that China’s government has announced that any automaker producing or importing more than 30,000 cars in China must ensure 10 percent of them are all-electric, plug-in hybrid, or hydrogen-powered by 2019. That number will rise to 12 percent in 2020.

In fact, the new regulations are actually more lenient than drafts of the rules had suggested: they scrap a 2018 introduction to give manufacturers more time to prepare, and will also excuse failure to meet the quota in the first year. So, really, the 12 percent target in 2020 is the first enforceable number.

That still doesn’t make it very easy, as the Wall Street Journal notes (paywall). Domestic automakers already make plenty of electric cars (largely at the government’s behest), which means that they should be able to meet the numbers, but Western firms will find it harder. In preparation, some have actually set up partnerships with Chinese companies to help them build electric vehicles in time.

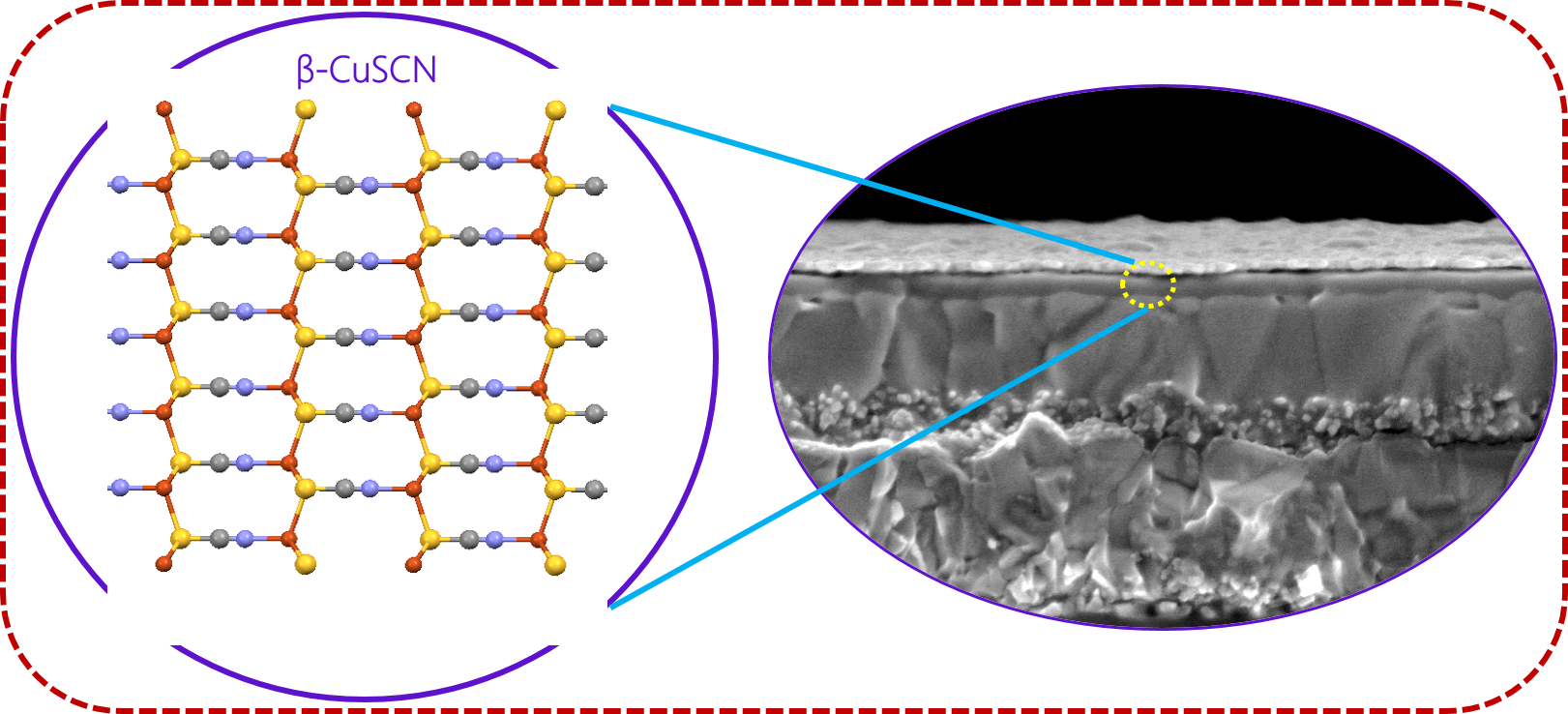

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) can offer high light-conversion efficiency with low manufacturing costs. But to be commercially viable, perovskite films must also be durable and not degrade under solar light over time. EPFL scientists have now greatly improved the operational stability of PSCs, retaining more than 95% of their initial efficiencies of over 20 % under full sunlight illumination at 60oC for more than 1000 hours. The breakthrough, which marks the highest stability for perovskite solar cells, is published in Science.

Challenges of stability

Conventional silicon solar cells have reached a point of maturation, with efficiencies plateauing around 25% and problems of high-cost manufacturing, heavyweight, and rigidity has remained largely unresolved. On the contrary, a relatively new photovoltaic technology based on perovskite solar cells has already achieved more than 22% efficiency.

It’s not every day scientists say a new kind of renewable energy could satisfy the majority of our power needs, so when they do, it’s worth leaning in close.

In a first-of-its-kind study, researchers have found that energy harvested from the evaporation of water in US lakes and reservoirs could power nearly 70 percent of the nation’s electricity demands, generating a whopping 325 gigawatts of electricity.

Alongside the great strides being made in solar and wind, biophysicist Ozgur Sahin from Columbia University says natural evaporation represents a massive unexplored resource of environmentally clean power generation, just waiting to be tapped.