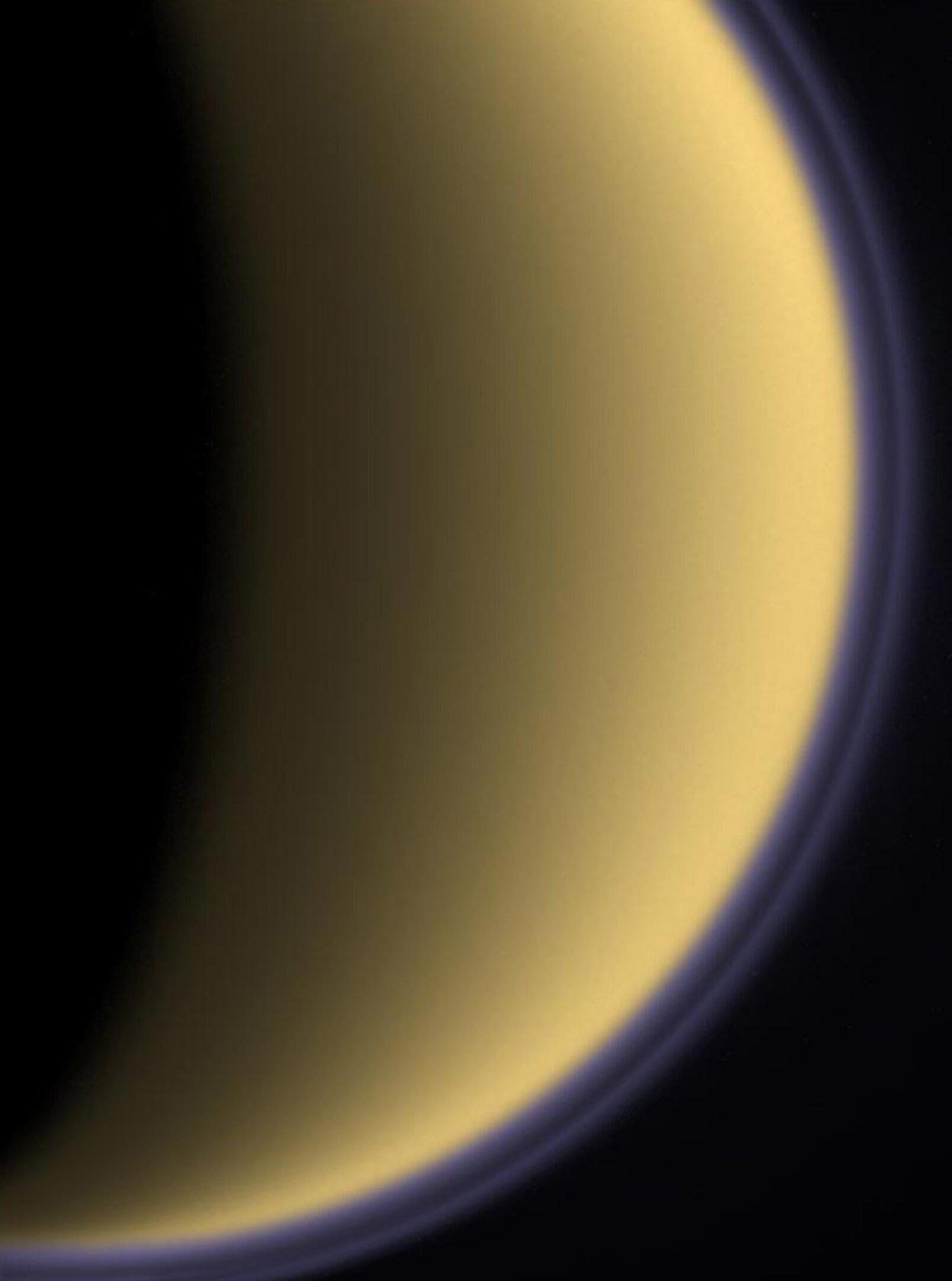

In the 17th century, astronomers Christiaan Huygens and Giovanni Cassini trained their telescopes on Saturn and uncovered a startling truth: the planet’s luminous bands were not solid appendages, but vast, separate rings composed of countless nested arcs.

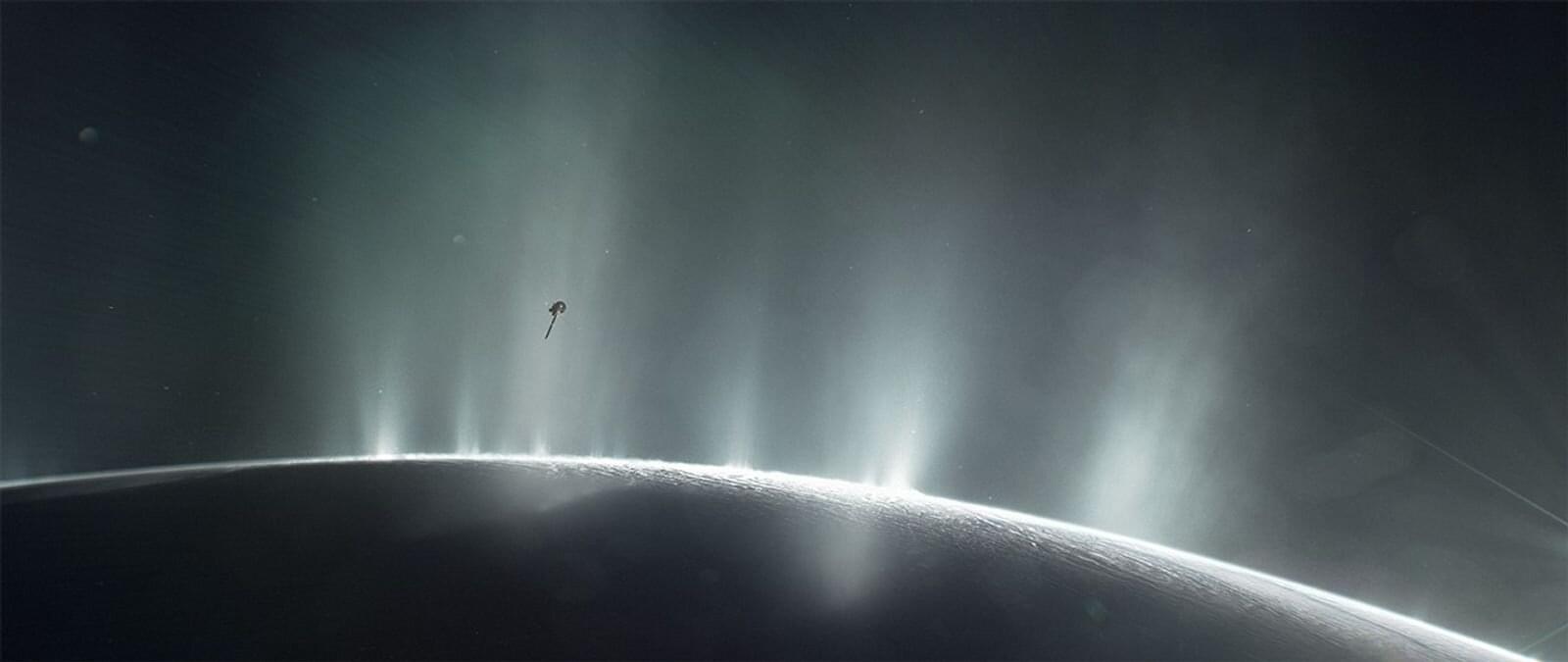

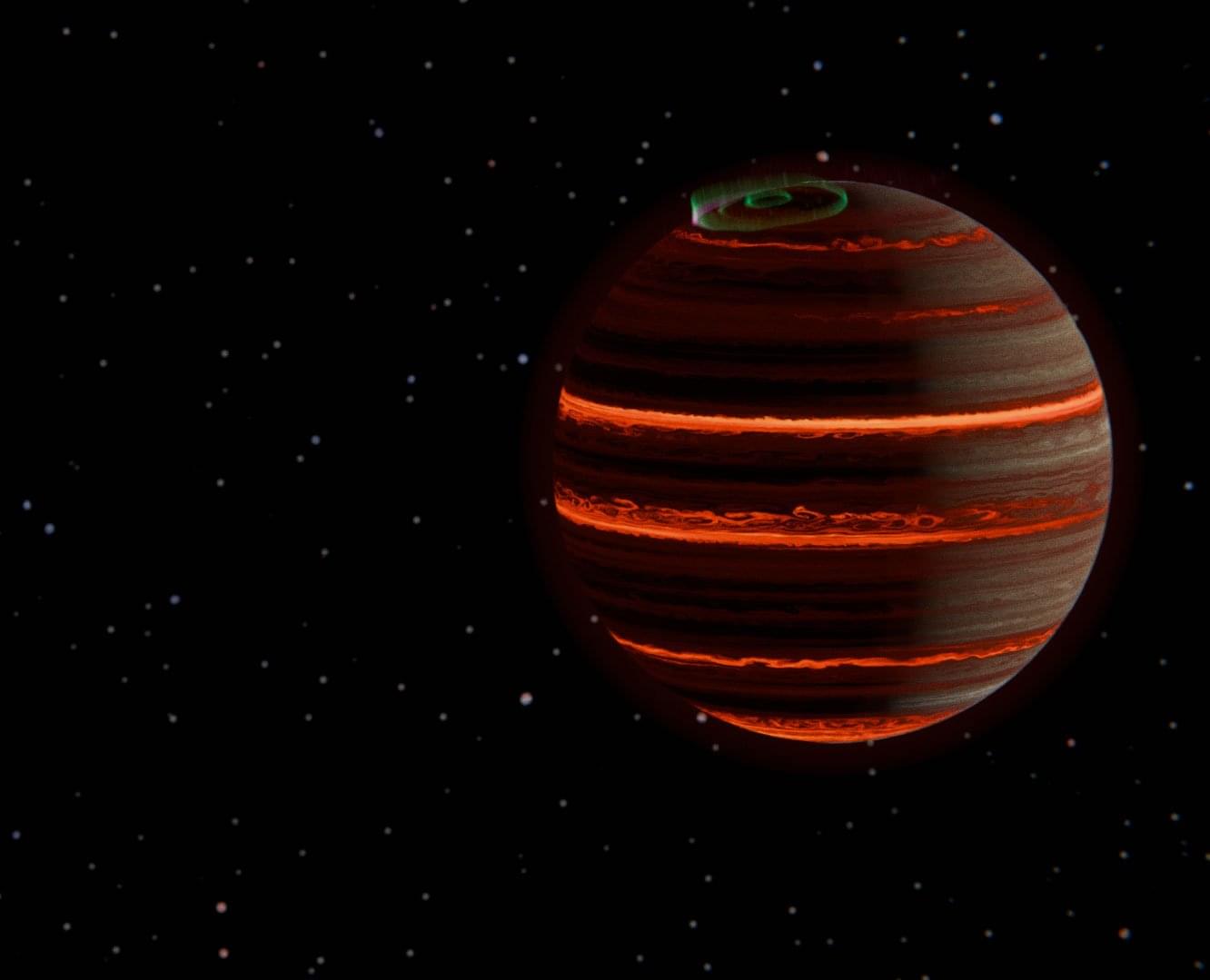

Centuries later, NASA’s Cassini–Huygens (Cassini) probe carried the exploration of Saturn even further. Beginning in 2005, it sent back a stream of spectacular images that transformed scientists’ understanding of the system. Among its most dramatic revelations were the towering geysers on Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, which blasted debris into space and left behind a faint sub-ring encircling the planet.

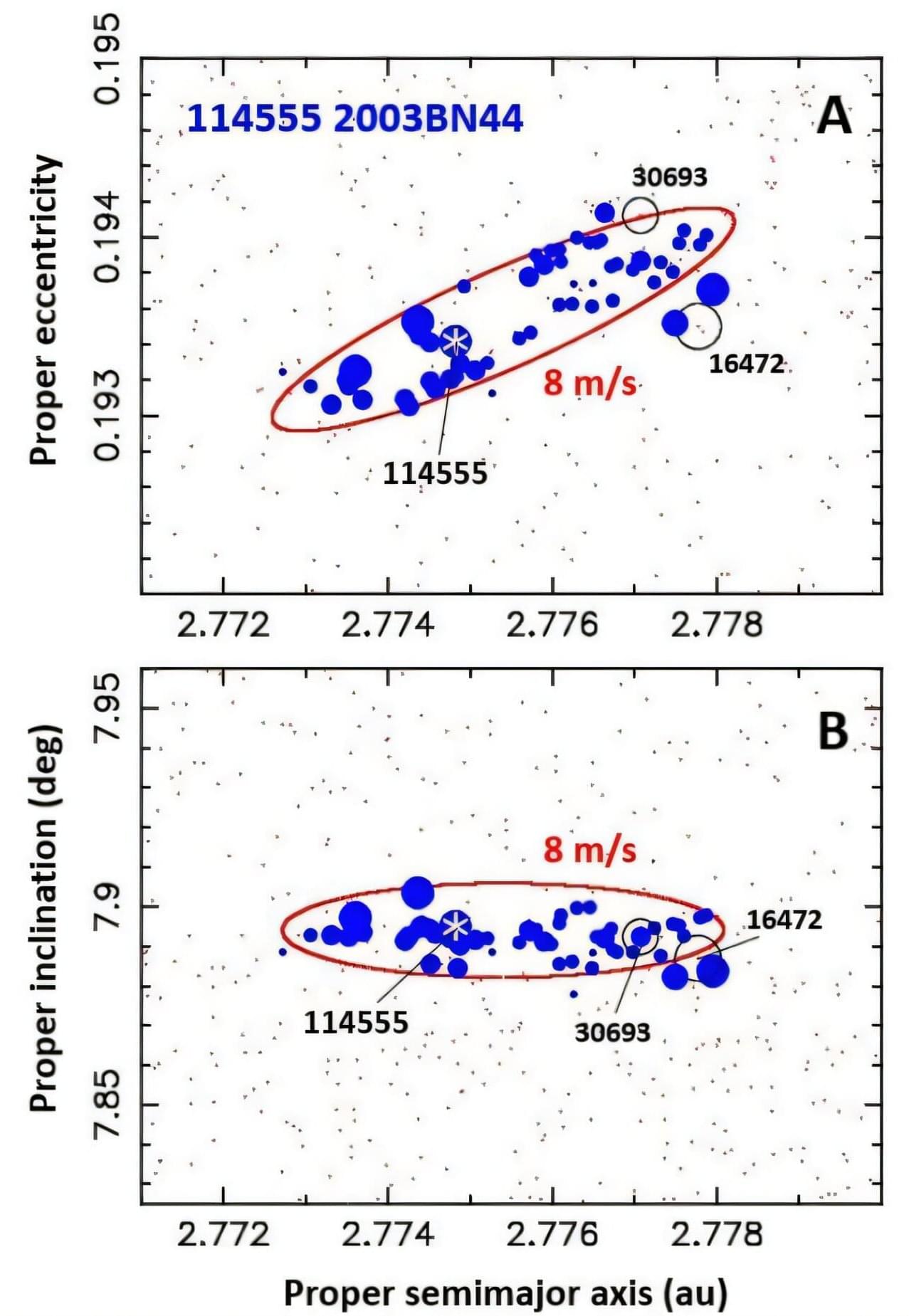

New supercomputer simulations from the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) based on the Cassini space probe’s data have found improved estimates of ice mass Enceladus is losing to space. These findings help with understanding and future robotic exploration of what’s below the surface of the icy moon, which might harbor life.