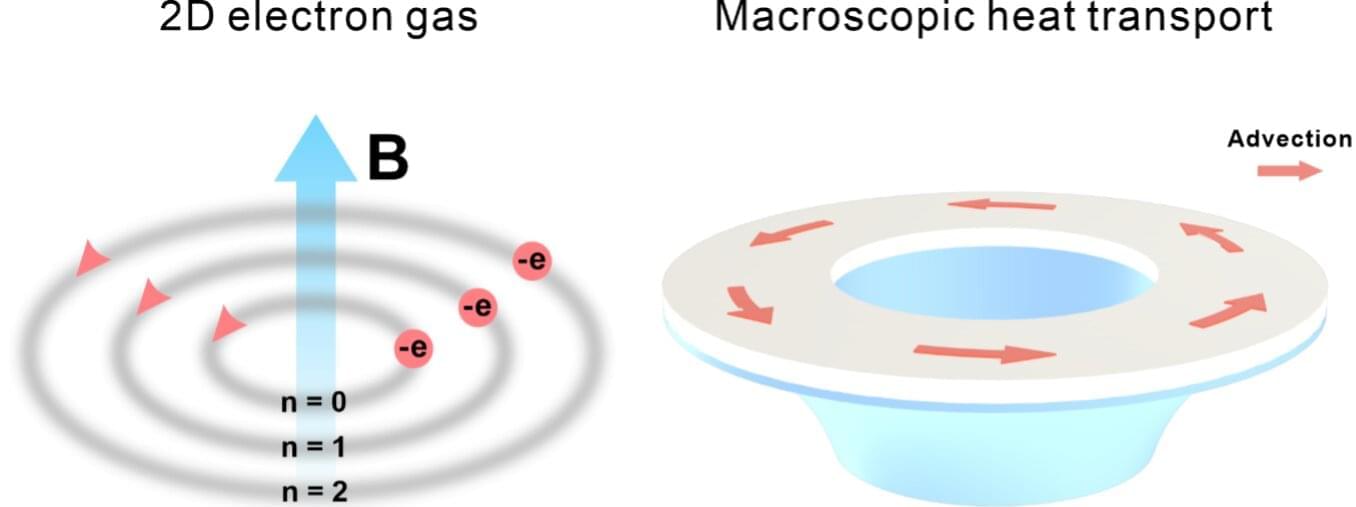

Preserving quantum information is key to developing useful quantum computing systems. But interacting quantum systems are chaotic and follow laws of thermodynamics, eventually leading to information loss. Physicists have long known of a strange exception, called dynamical freezing, when quantum systems shaken at precisely tuned frequencies evade these laws. But how long can this phenomenon postpone thermodynamics?

Not forever, but for an astonishingly long time, Cornell physicists have determined, giving the first quantitative answer. Using a new mathematical framework, they demonstrate that the frozen state can be stabilized long enough to be a useful strategy for preserving information in quantum systems. This can be a promising route for maintaining coherence in quantum computers as the numbers of qubits scale up to the millions.

“It’s like asking, how do you evade the laws of physics from eventually taking over?” said Debanjan Chowdhury, associate professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences. “Imagine that you had a hot cup of coffee that even without a heater, stayed hot. Or a block of ice placed on a heater that never melts. Is that even possible? This has been one of the big open problems in the field of quantum many-body systems.”