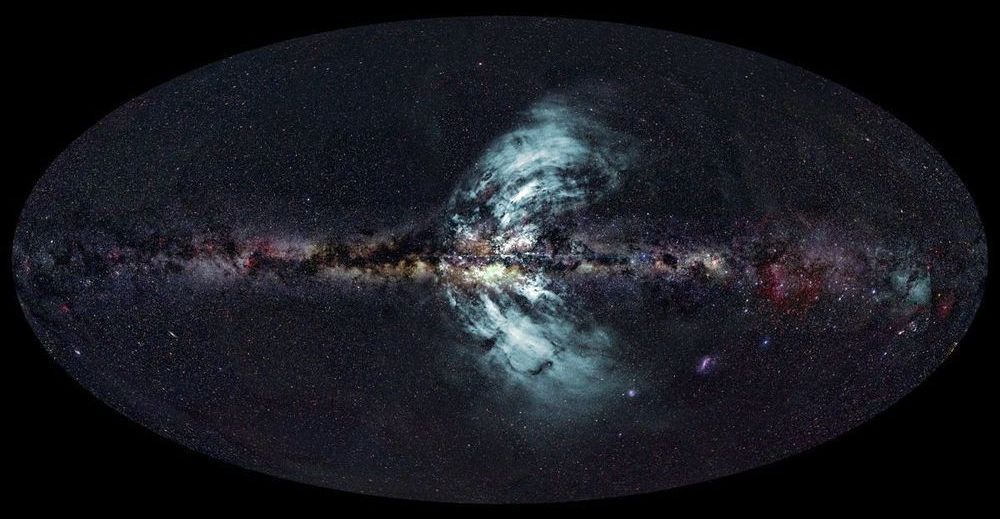

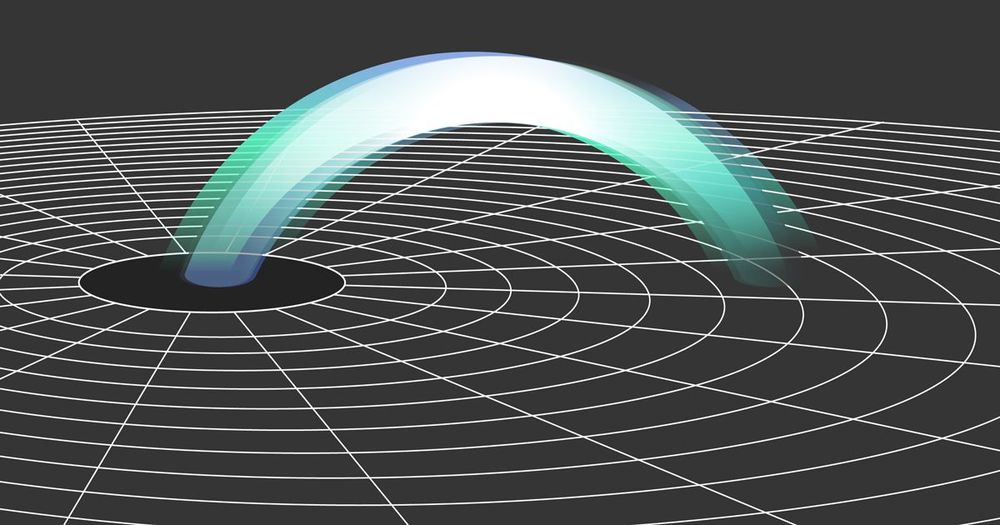

For the first time, physicists have calculated exactly what kind of singularity lies at the center of a realistic black hole.

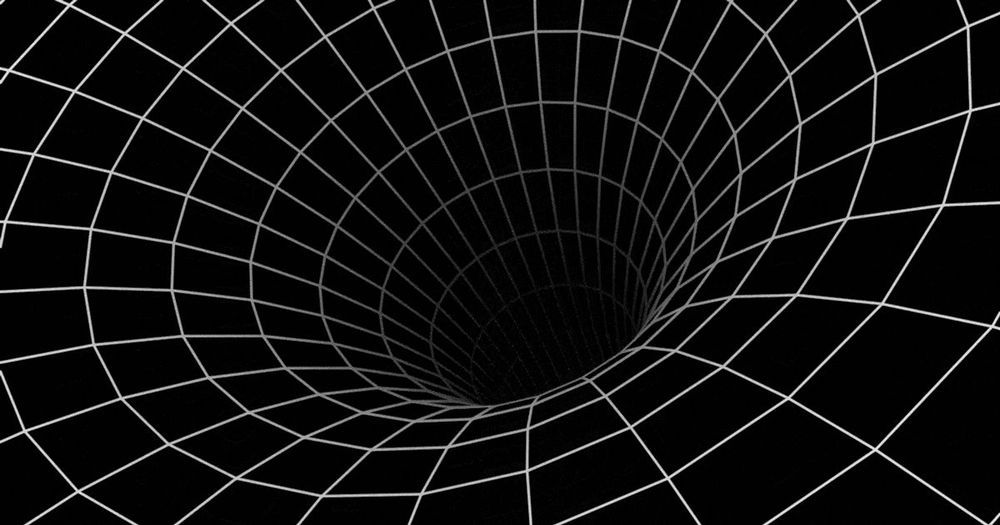

Researchers have identified a metal that conducts electricity without conducting heat — an incredibly useful property that defies our current understanding of how conductors work.

The metal, found in 2017, contradicts something called the Wiedemann-Franz Law, which basically states that good conductors of electricity will also be proportionally good conductors of heat, which is why things like motors and appliances get so hot when you use them regularly.

But a team in the US showed this isn’t the case for metallic vanadium dioxide (VO2) — a material that’s already well known for its strange ability to switch from a see-through insulator to a conductive metal at the temperature of 67 degrees Celsius (152 degrees Fahrenheit).

In 1900, so the story goes, prominent physicist Lord Kelvin addressed the British Association for the Advancement of Science with these words: “There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now.”

How wrong he was. The following century completely turned physics on its head. A huge number of theoretical and experimental discoveries have transformed our understanding of the universe, and our place within it.

Don’t expect the next century to be any different. The universe has many mysteries that still remain to be uncovered—and new technologies will help us to solve them over the next 50 years.

Ira Pastor, ideaXme exponential health ambassador, interviews Dr. Ronald Mallett, Professor Emeritus, Theoretical Physics, Department of Physics at the University of Connecticut.

Ira Pastor Comments:

Time travel is the concept of movement between certain points in time, analogous to movement between different points in space, by an object or a person, typically with the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine.

Time travel is a widely recognized concept in philosophy and fiction and the idea of a time machine was originally popularized by H. G. Wells’ 1895 novel The Time Machine.

Forward time travel, outside the usual sense of the perception of time, is an extensively observed phenomenon and well-understood within the framework of special relativity and general relativity and making one body advance a few milliseconds compared to another body has been demonstrated in experiments comparing atomic clocks on jets and satelites versus the earth.

As for backward time travel, it is possible to find solutions in general relativity that allow for it, in a theoretical system known as a “closed timelike curve” (sometimes abbreviated CTC), which is where the world line of an object (the path that an object traces in 4-dimensional space-time) follows a curious path where it eventually returns to the exact same coordinates in space and time that it was at previously. In other words, a closed timelike curve is the mathematical result of physics equations that allows for time travel to the past.

In 2016, Attila Krasznahorkay made news around the world when his team published its discovery of evidence of a fifth force of nature. Now, the scientists are making news again with a second observation of the same force, which may be the beginning of a unified fifth force theory. The researchers have made their original LaTeX paper available prior to acceptance by a peer-reviewed journal. Study of the hypothesized fifth force, a subfield all by itself, is centered on trying to explain missing pieces in our understanding of physics, like dark matter, which could be expanded or validated by an important new discovery or piece of evidence.

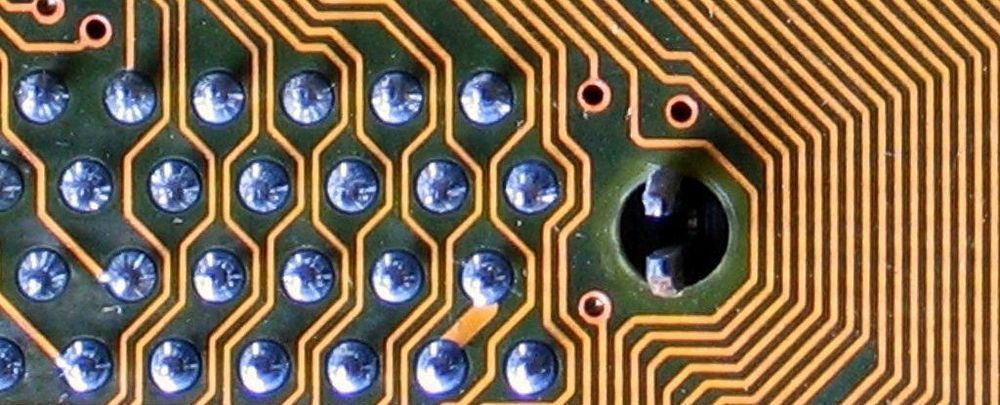

Scientists hope that the future of gravitational wave detection will allow them to directly observe a mysterious kind of black hole.

Gravitational wave detectors have seen direct evidence of black holes with roughly the mass of giant stars, while the Event Horizon Telescope produced an image of a supermassive black hole billions of times the mass of our Sun. But in the middle are intermediate-mass black holes, or IMBHs, which weigh between 100 and 100,000 times the mass of the Sun and have yet to be directly observed. Researchers hope that their new mathematical work will “pave the way” for future research into these black holes using gravitational wave detectors, according to the paper published today in Nature Astronomy.