Go to https://squarespace.com/pbs to get a free trial and 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain.

PBS Member Stations rely on viewers like you. To support your local station, go to: http://to.pbs.org/DonateSPACE

Sign Up on Patreon to get access to the Space Time Discord!

https://www.patreon.com/pbsspacetime.

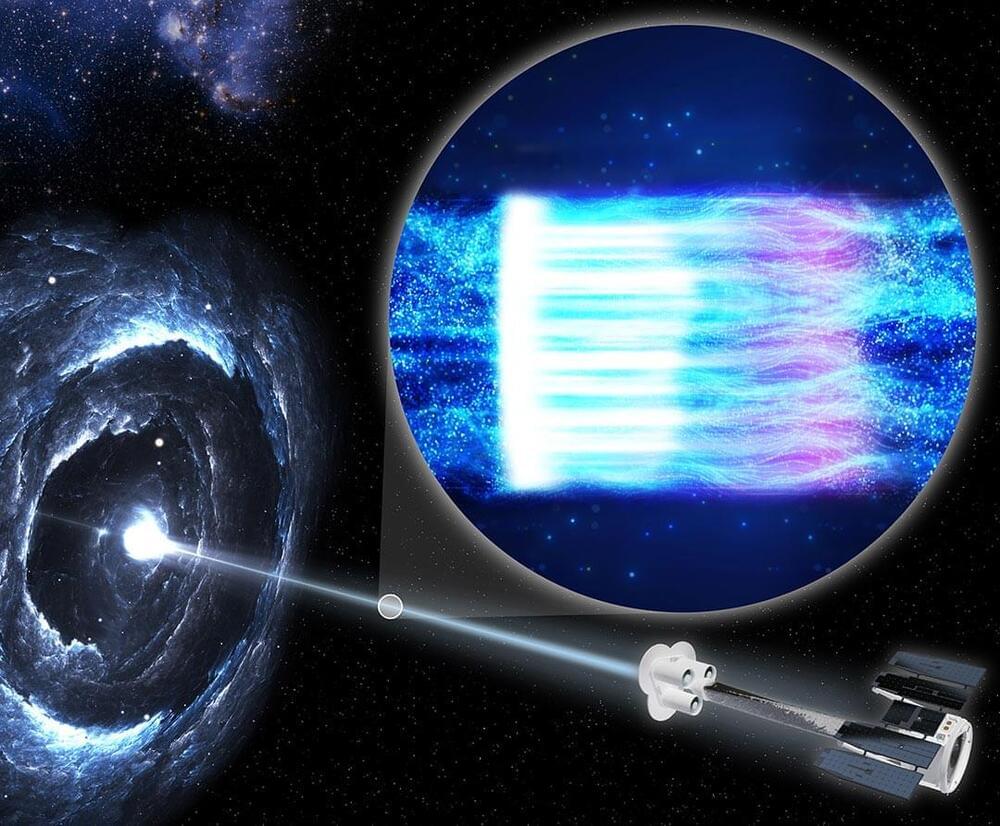

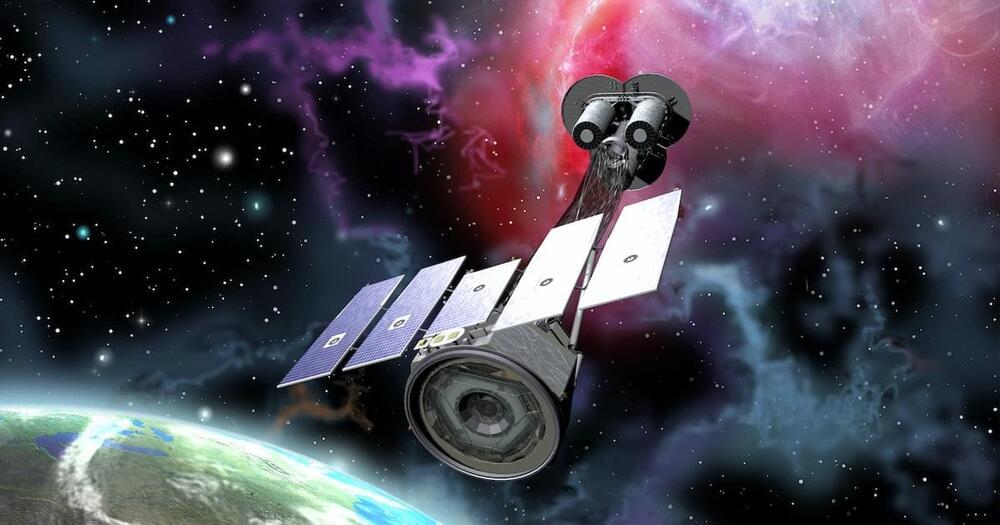

I’m going to tell you about the craziest proposal for an astrophysics mission that has a good chance of actually happening. A train of spacecraft sailing the sun’s light to a magical point out there in space where the Sun’s own gravity turns it into a gigantic lens. What could such a solar-system-sized telescope do? Pretty much anything. But definitely map the surfaces of alien worlds.

Check out the Space Time Merch Store.

https://www.pbsspacetime.com/shop.

Sign up for the mailing list to get episode notifications and hear special announcements!