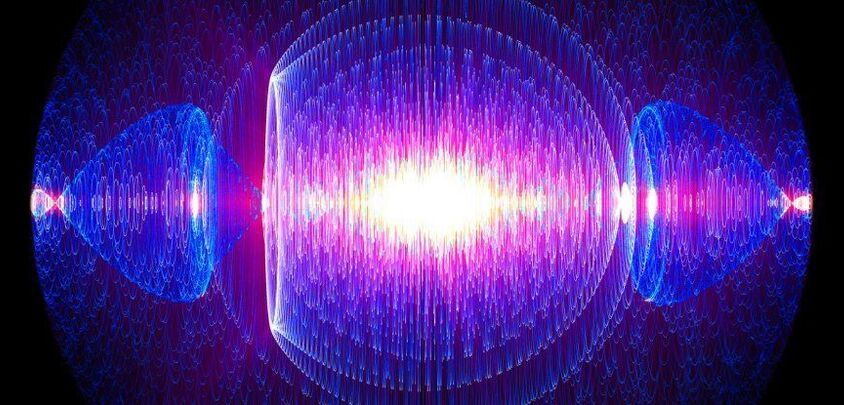

Computer models of merging neutron stars predicts new signature in the gravitational waves to tell when this happens.

Neutron stars are among the densest objects in the universe. If our Sun, with its radius of 700,000 kilometers were a neutron star, its mass would be condensed into an almost perfect sphere with a radius of around 12 kilometers. When two neutron stars collide and merge into a hyper-massive neutron star, the matter in the core of the new object becomes incredibly hot and dense. According to physical calculations, these conditions could result in hadrons such as neutrons and protons, which are the particles normally found in our daily experience, dissolving into their components of quarks and gluons and thus producing a quark-gluon plasma.

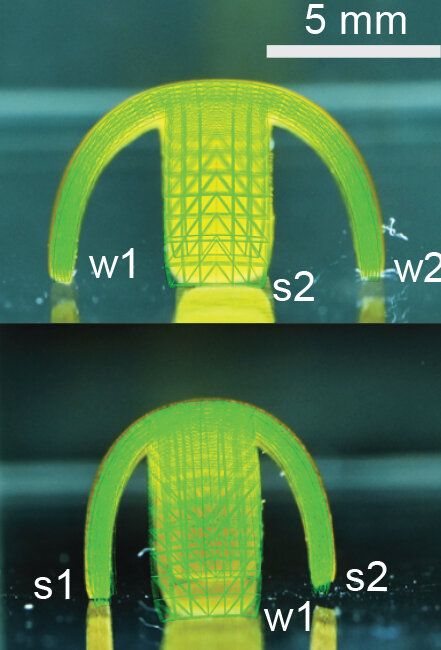

This simulation shows the density of the ordinary matter (mostly neutrons) in red-yellow. Shortly after the two stars merge the extremely dense center turns green, depicting the formation of the quark-gluon plasma.