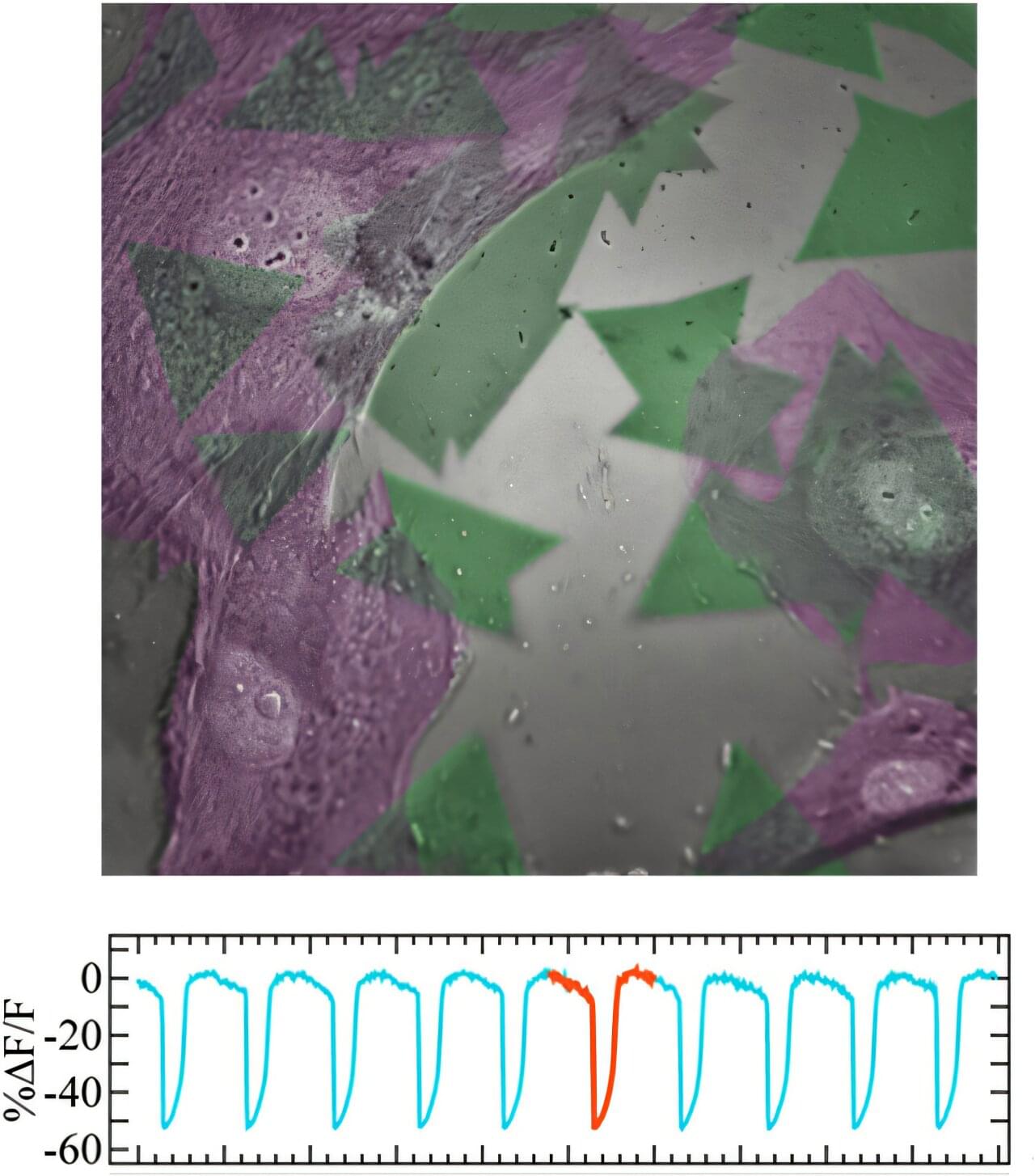

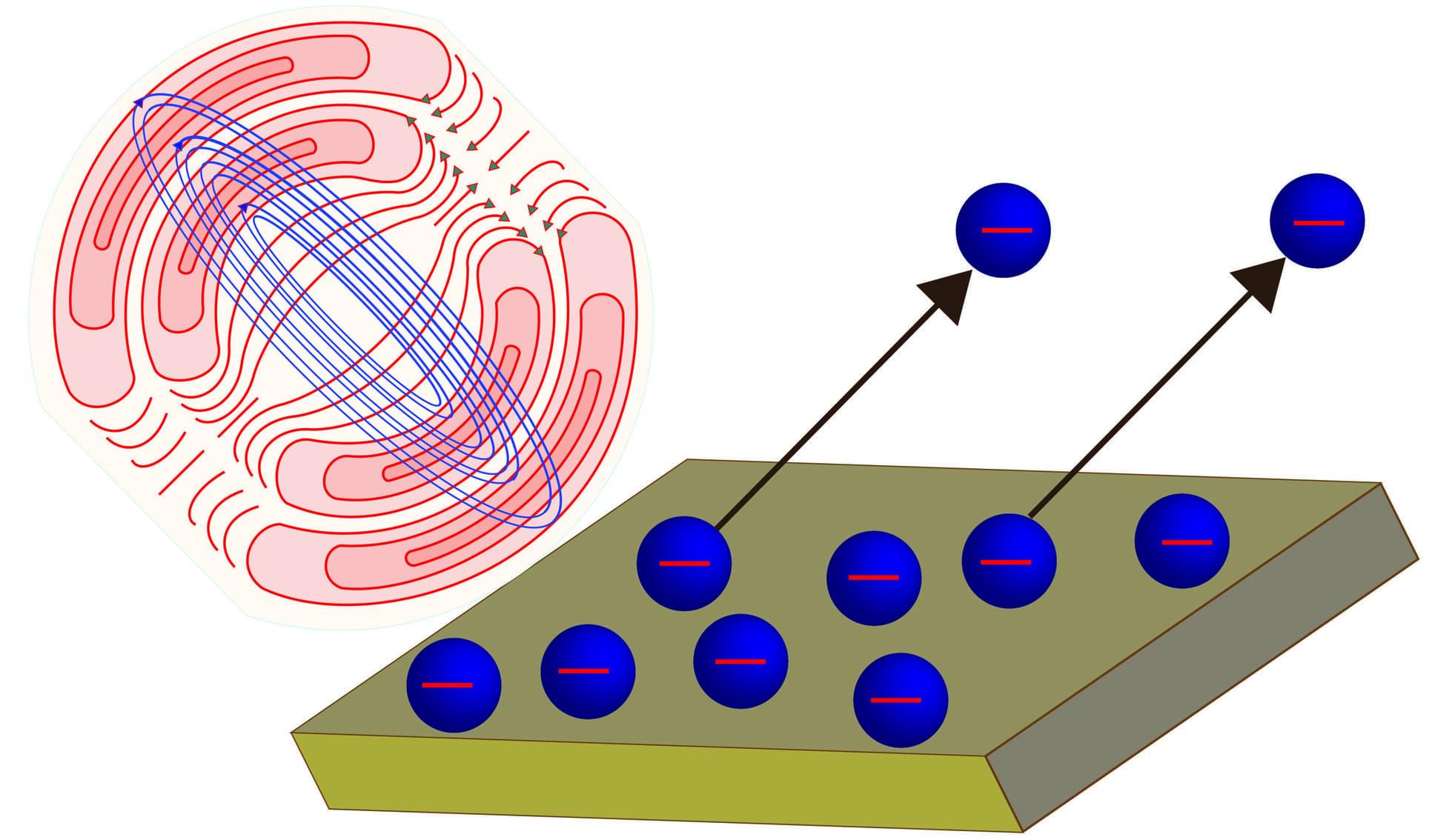

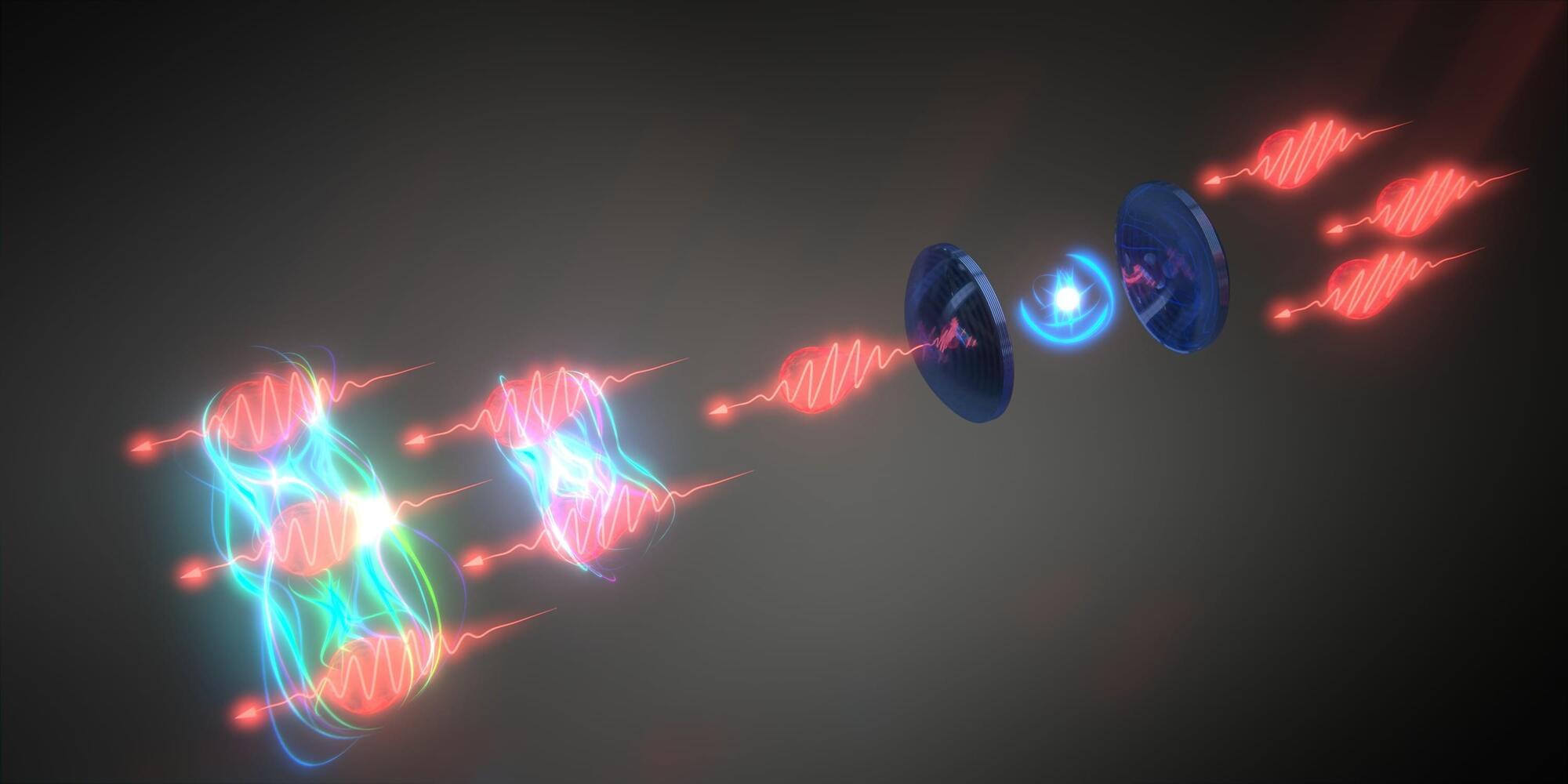

For decades, scientists have relied on electrodes and dyes to track the electrical activity of living cells. Now, engineers at the University of California San Diego have discovered that quantum materials just a single atom thick can do the job—using only light.

A new study, published in Nature Photonics, shows that these ultra-thin semiconductors, which trap electrons in two dimensions, can be used to sense the biological electrical activity of living cells with high speed and resolution.

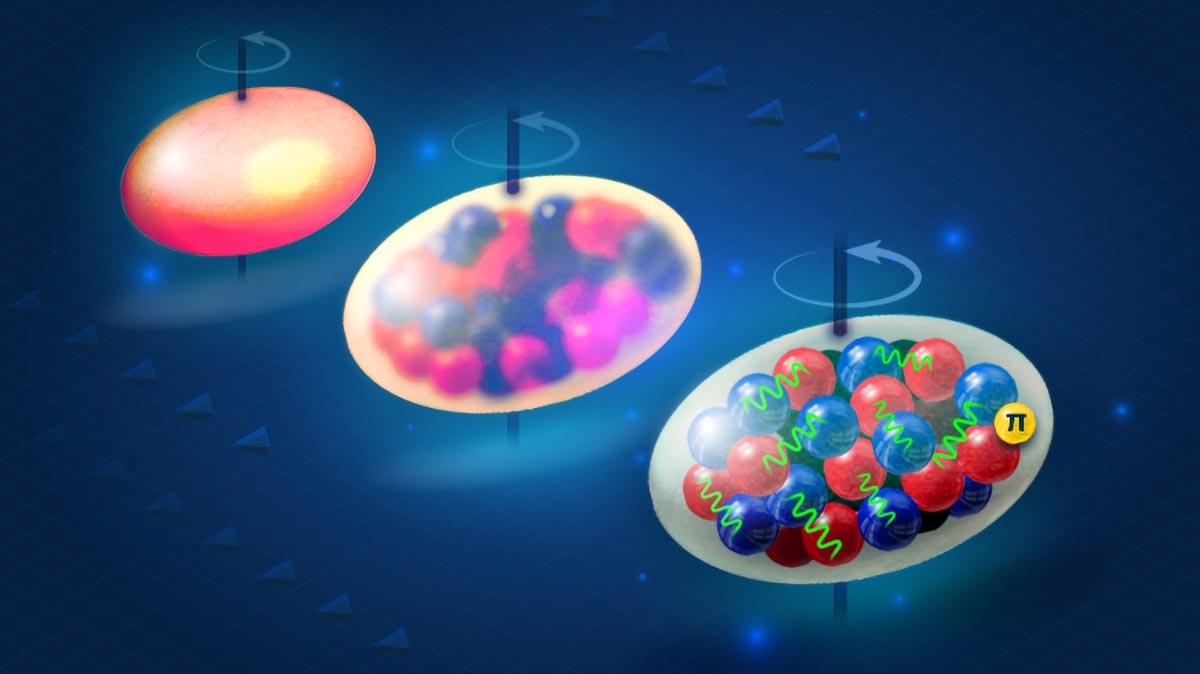

Scientists have continually been seeking better ways to track the electrical activity of the body’s most excitable cells, such as neurons, heart muscle fibers and pancreatic cells. These tiny electrical pulses orchestrate everything from thought to movement to metabolism, but capturing them in real time and at large scales has remained a challenge.