This conversation between Max Tegmark and Joel Hellermark was recorded in April 2024 at Max Tegmark’s MIT office. An edited version was premiered at Sana AI Summit on May 15 2024 in Stockholm, Sweden.

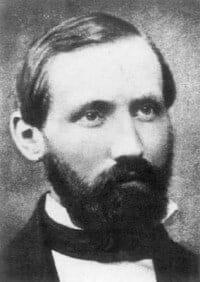

Max Tegmark is a professor doing AI and physics research at MIT as part of the Institute for Artificial Intelligence \& Fundamental Interactions and the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines. He is also the president of the Future of Life Institute and the author of the New York Times bestselling books Life 3.0 and Our Mathematical Universe. Max’s unorthodox ideas have earned him the nickname “Mad Max.”

Joel Hellermark is the founder and CEO of Sana. An enterprising child, Joel taught himself to code in C at age 13 and founded his first company, a video recommendation technology, at 16. In 2021, Joel topped the Forbes 30 Under 30. This year, Sana was recognized on the Forbes AI 50 as one of the startups developing the most promising business use cases of artificial intelligence.

Timestamps.

From cosmos to AI (00:00:00)

Creating superhuman AI (00:05:00)

Superseding humans (00:09:32)

State of AI (00:12:15)

Self-improving models (00:16:17)

Human vs machine (00:18:49)

Gathering top minds (00:19:37)

The “bananas” box (00:24:20)

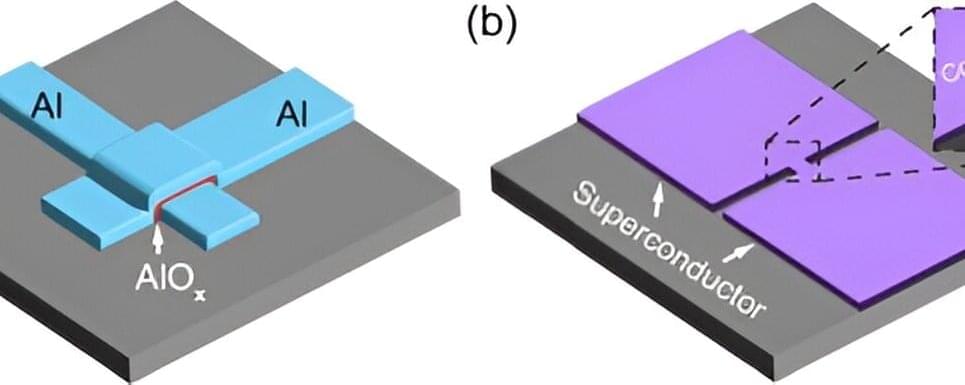

Future Architecture (00:26:50)

AIs evaluating AIs (00:29:17)

Handling AI safety (00:35:41)

AI fooling humans? (00:40:11)

The utopia (00:42:17)

The meaning of life (00:43:40)

Follow Sana.

X — https://twitter.com/sanalabs.

LinkedIn — / sana-labs.

Instagram — / sanalabs.

Try Sana AI for free — https://sana.ai