Coating implantable electronics in the polymer PEDOT can extend their life, which could make more common in the future.

Future cities could be 3D printed – using concrete made with recycled glass.

3D printed concrete may lead to a shift in architecture and construction. Because it can be used to produce new shapes and forms that current technologies struggle with, it may change the centuries-old processes and procedures that are still used to construct buildings, resulting in lower costs and saved time.

New battery material offers promise for the development of all-solid batteries.

In the quest for the perfect battery, scientists have two primary goals: create a device that can store a great deal of energy and do it safely. Many batteries contain liquid electrolytes, which are potentially flammable.

As a result, solid-state lithium-ion batteries, which consist of entirely solid components, have become increasingly attractive to scientists because they offer an enticing combination of higher safety and increased energy density — which is how much energy the battery can store for a given volume.

The Apollo missions to the Moon brought a total of 2,196 rock samples to Earth. But NASA has only just started opening one of the last ones, collected 50 years ago.

For all that time, some tubes were kept sealed so that they could be studied years later, with the help of the latest technical breakthroughs.

NASA knew “science and technology would evolve and allow scientists to study the material in new ways to address new questions in the future,” Lori Glaze, director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters, said in a statement.

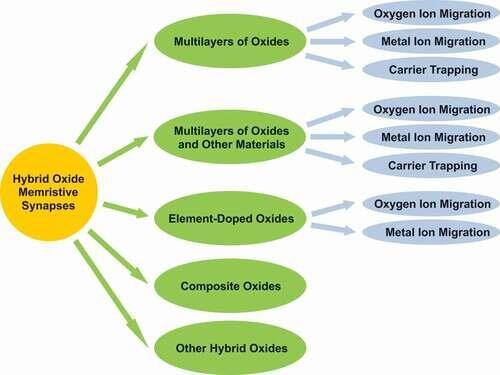

Scientists are getting better at making neurone-like junctions for computers that mimic the human brain’s random information processing, storage and recall. Fei Zhuge of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and colleagues reviewed the latest developments in the design of these “memristors” for the journal Science and Technology of Advanced Materials.

Computers apply artificial intelligence programs to recall previously learned information and make predictions. These programs are extremely energy-and time-intensive: typically, vast volumes of data must be transferred between separate memory and processing units. To solve this, researchers have been developing computer hardware that allows for more random and simultaneous information transfer and storage, much like the human brain.

Electronic circuits in these “neuromorphic” computers include memristors that resemble the synaptic junctions between neurones. Energy flows through a material from one electrode to another, much like a neurone firing a signal across the synapse to the next neurone. Scientists are now finding ways to better tune this intermediate material so the information flow is more stable and reliable.

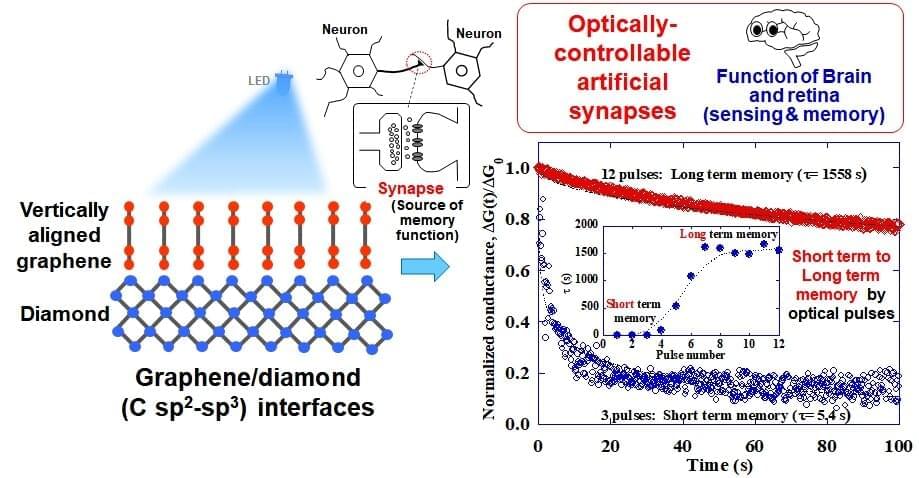

The human brain holds the secret to our unique personalities. But did you know that it can also form the basis of highly efficient computing devices? Researchers from Nagoya University, Japan, recently showed how to do this, through graphene-diamond junctions that mimic some of the human brain’s functions.

But, why would scientists try to emulate the human brain? Today, existing computer architectures are subjected to complex data, limiting their processing speed. The human brain, on the other hand, can process highly complex data, such as images, with high efficiency. Scientists have, therefore, tried to build “neuromorphic” architectures that mimic the neural network in the brain.

A phenomenon essential for memory and learning is “synaptic plasticity,” the ability of synapses (neuronal links) to adapt in response to an increased or decreased activity. Scientists have tried to recreate a similar effect using transistors and “memristors” (electronic memory devices whose resistance can be stored). Recently developed light-controlled memristors, or “photomemristors,” can both detect light and provide non-volatile memory, similar to human visual perception and memory. These excellent properties have opened the door to a whole new world of materials that can act as artificial optoelectronic synapses!

Fluctuating light from a black hole, observed over 15 years, has revealed more about the way these enigmatic objects feed.

First, a structure called a corona forms around the outside of the event horizon. Then, powerful jets of plasma launch from the poles, punching material from the corona out into interstellar space at speeds close to that of light in a vacuum.

The finding – likened to the rhythmic pounding of a ‘heartbeat’ – resolves a long open question in black hole science.

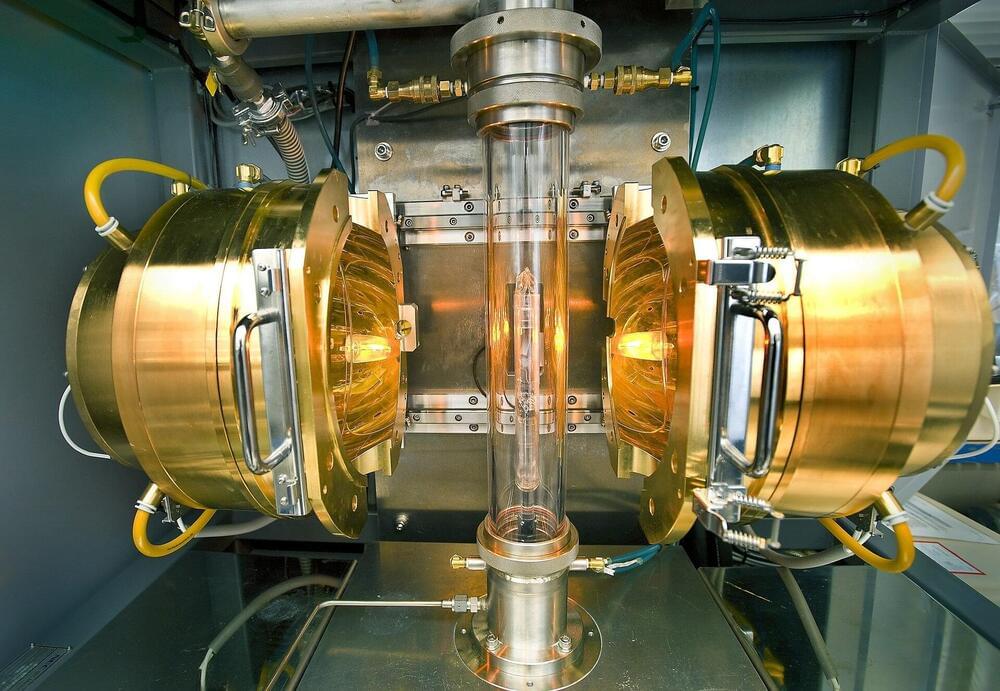

In the simplest terms, superconductivity between two or more objects means zero wasted electricity. It means electricity is being transferred between these objects with no loss of energy.

Many naturally occurring elements and minerals like lead and mercury have superconducting properties. And there are modern applications that currently use materials with superconducting properties, including MRI machines, maglev trains, electric motors and generators.

Usually, superconductivity in materials happens in low-temperature environments or at high temperatures at very high pressures. The holy grail of superconductivity today is to find or create materials that can transfer energy between each other in a non-pressurized room-temperature environment.

The ongoing interaction between two galaxies 320 million light-years away has been captured in a gorgeous Hubble image.

They’re collectively known as Arp 282 in Halton Arp’s Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies, and they consist of a large barred spiral galaxy named NGC 169, about 140,000 light-years across, and a much smaller polar-ring galaxy named IC 1,559, which is about 40,000 light-years across.

These two galaxies have drawn close enough together that they’re exchanging material. That’s not unusual: Although space is vast and mostly empty, galaxies are gravitationally drawn together, perhaps channeled along strands of the invisible cosmic web that stretches across and plays a vital role in shaping the Universe.

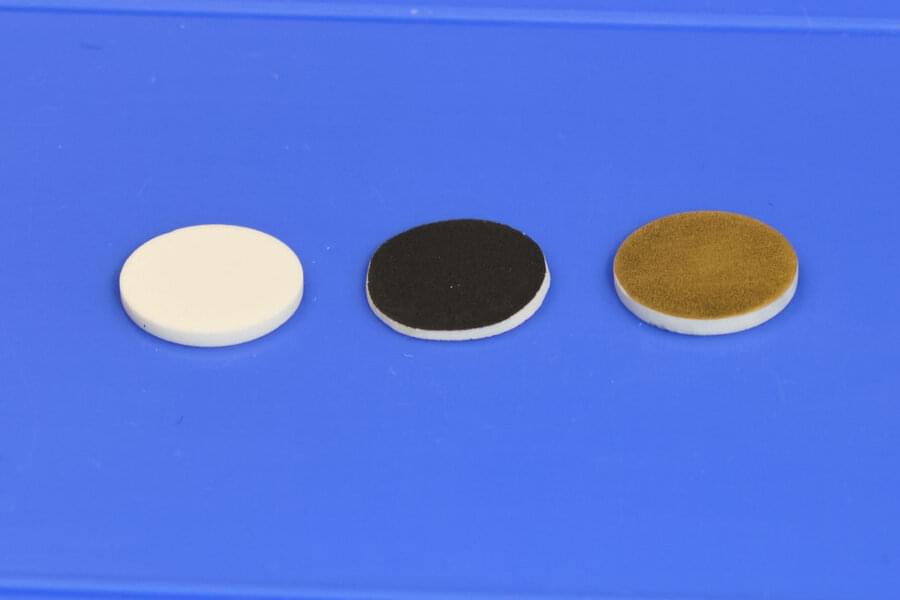

In the endless quest to pack more energy into batteries without increasing their weight or volume, one especially promising technology is the solid-state battery. In these batteries, the usual liquid electrolyte that carries charges back and forth between the electrodes is replaced with a solid electrolyte layer. Such batteries could potentially not only deliver twice as much energy for their size, they also could virtually eliminate the fire hazard associated with today’s lithium-ion batteries.

But one thing has held back solid-state batteries: Instabilities at the boundary between the solid electrolyte layer and the two electrodes on either side can dramatically shorten the lifetime of such batteries. Some studies have used special coatings to improve the bonding between the layers, but this adds the expense of extra coating steps in the fabrication process. Now, a team of researchers at MIT and Brookhaven National Laboratory have come up with a way of achieving results that equal or surpass the durability of the coated surfaces, but with no need for any coatings.

The new method simply requires eliminating any carbon dioxide present during a critical manufacturing step, called sintering, where the battery materials are heated to create bonding between the cathode and electrolyte layers, which are made of ceramic compounds. Even though the amount of carbon dioxide present is vanishingly small in air, measured in parts per million, its effects turn out to be dramatic and detrimental. Carrying out the sintering step in pure oxygen creates bonds that match the performance of the best coated surfaces, without that extra cost of the coating, the researchers say.