In an ideal world, an AI model looking for new materials to build better batteries would be trained on millions or even hundreds of millions of data points.

But for emerging next-generation battery chemistries that don’t have decades of research behind them, waiting for new studies takes time the world doesn’t have.

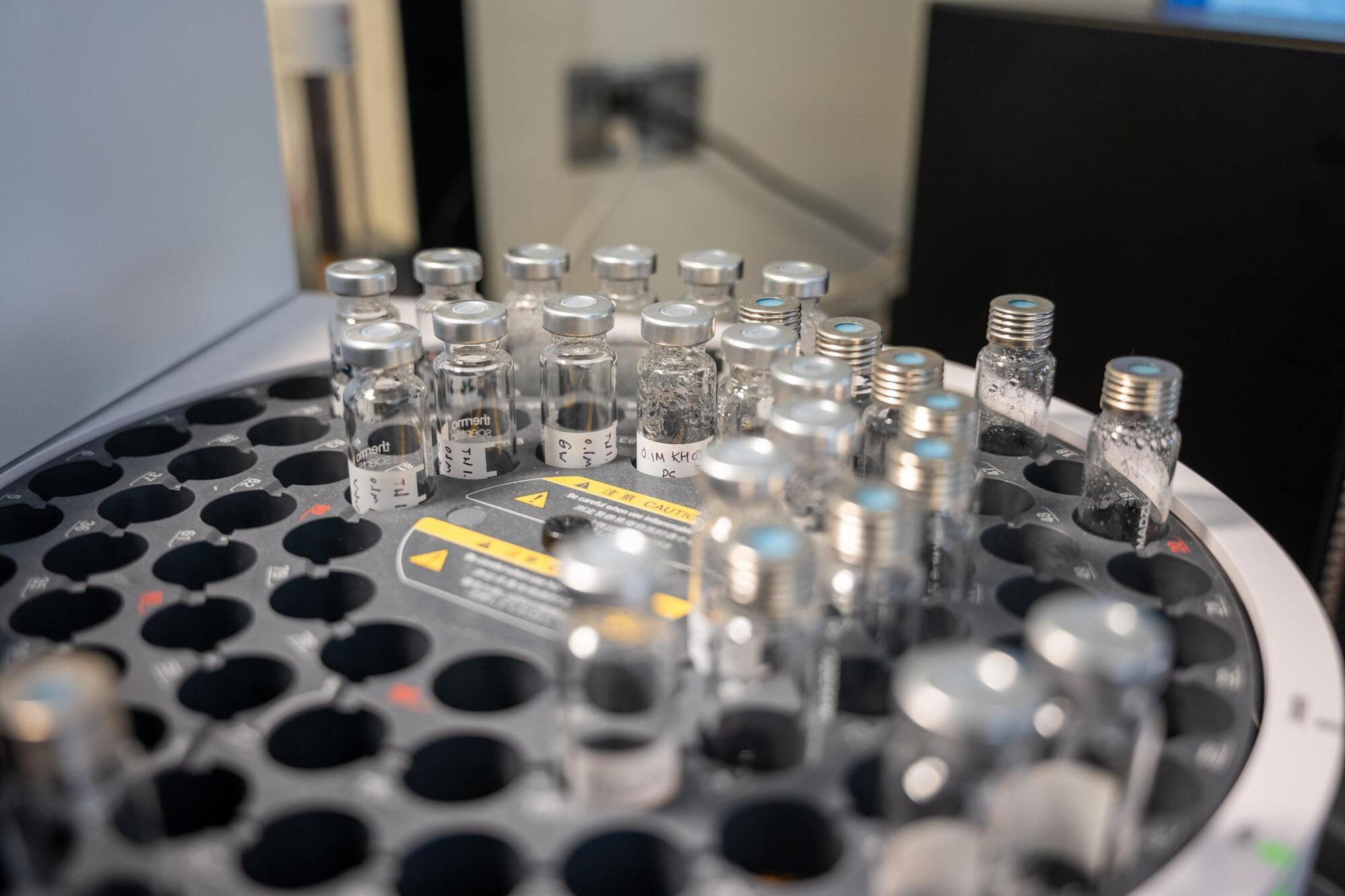

“Each experiment takes up to weeks, months to get data points,” said University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME) Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellow Ritesh Kumar. “It’s just infeasible to wait until we have millions of data to train these models.”