In solid materials, magnetism generally originates from the alignment of electron spins. For instance, in the ferromagnet iron, the overall net magnetization is prompted by the alignment of spins in the same direction.

Microwave dielectric ceramics are the cornerstone of wireless communication devices, widely utilized in mobile communications, satellite radar, GPS, Bluetooth, and WLAN applications. Components made from these ceramic materials, such as filters, resonators, and dielectric antennas, are extensively used in wireless communication networks.

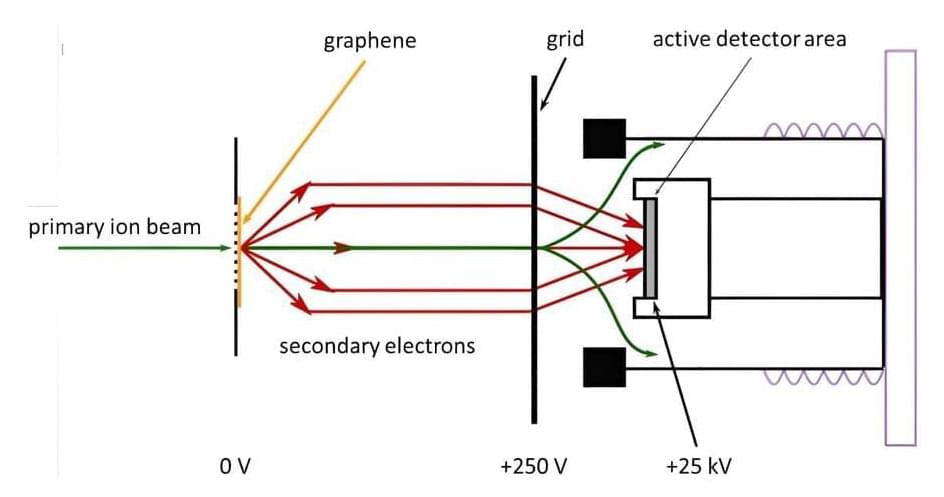

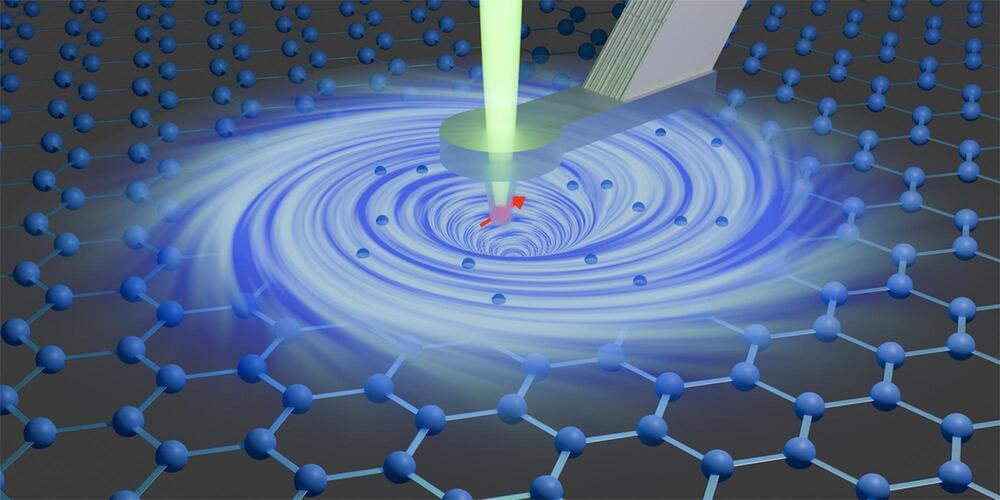

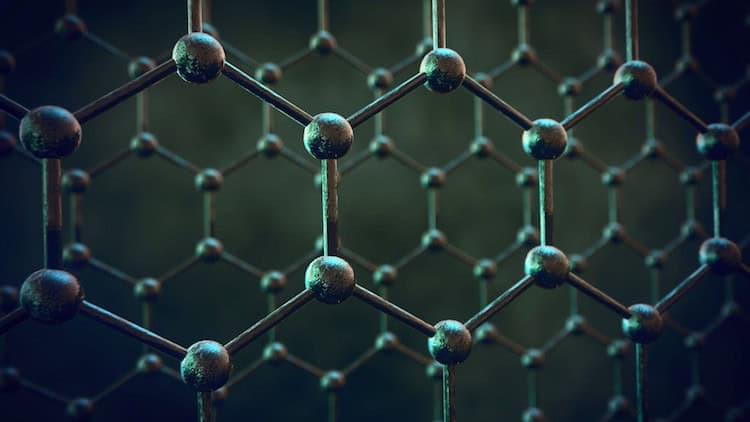

Two-dimensional materials such as graphene promise to form the basis of incredibly small and fast technologies, but this requires a detailed understanding of their electronic properties. New research demonstrates that fast electronic processes can be probed by irradiating the materials with ions first.

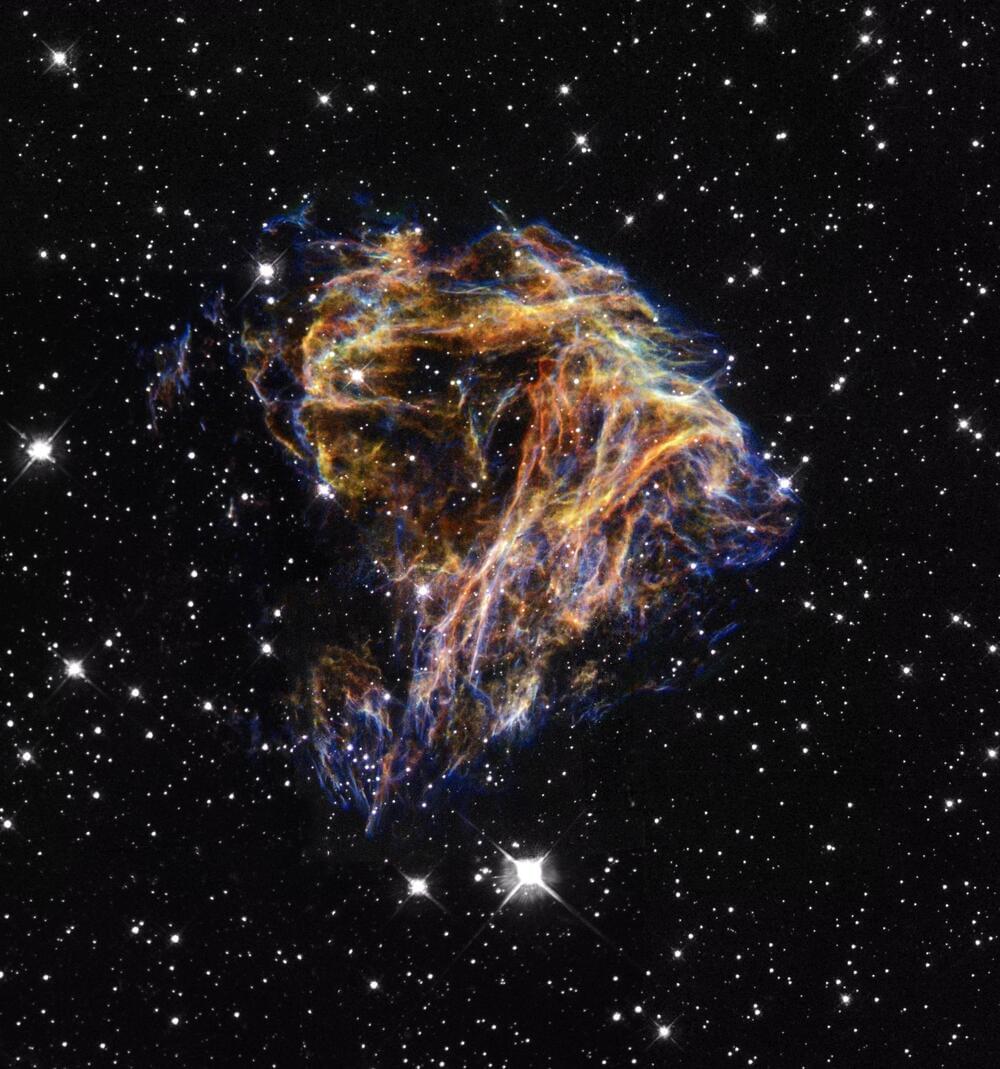

Looking like a glittering cosmic geode, a trio of dazzling stars blaze from the hollowed-out cavity of a reflection nebula in this new image from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. The triple-star system is made up of the variable star HP Tau, HP Tau G2, and HP Tau G3.

HP Tau is known as a T Tauri star, a type of young variable star that hasn’t begun nuclear fusion yet but is beginning to evolve into a hydrogen-fueled star similar to our sun. T Tauri stars tend to be younger than 10 million years old―in comparison, our sun is around 4.6 billion years old―and are often found still swaddled in the clouds of dust and gas from which they formed.

As with all variable stars, HP Tau’s brightness changes over time. T Tauri stars are known to have both periodic and random fluctuations in brightness. The random variations may be due to the chaotic nature of a developing young star, such as instabilities in the accretion disk of dust and gas around the star, material from that disk falling onto the star and being consumed, and flares on the star’s surface. The periodic changes may be due to giant sunspots rotating in and out of view.

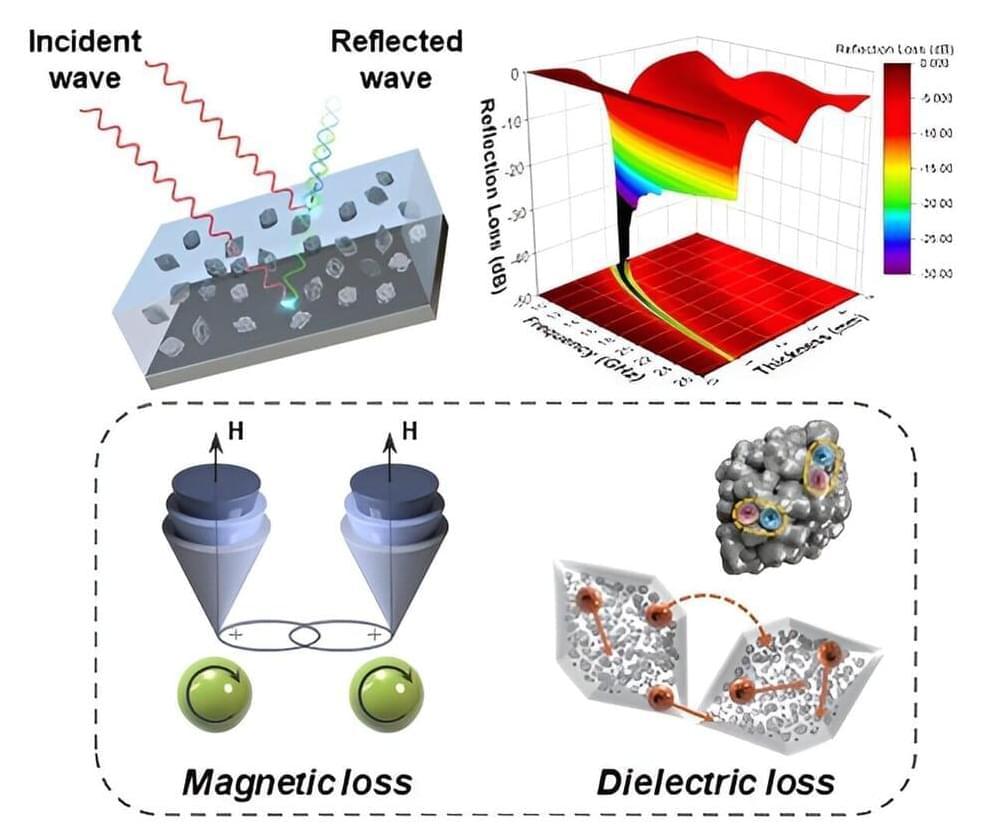

A research team from the Department of Functional Composites in Composites Research Division at Korea Institute of Materials Science (KIMS) has successfully developed electromagnetic wave absorbers based on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that enhance dielectric and magnetic losses in the gigahertz (GHz) frequency band. The research was published in the journal Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials on February 5, 2024.

A new nucleosynthesis process denoted as the νr-process has been suggested by scientists from GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, Technische Universität Darmstadt, and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics. It operates when neutron-rich material is exposed to a high flux of neutrinos.

A new type of bioplastic could help reduce the plastic industry’s environmental footprint. Researchers led by the University of California San Diego have developed a biodegradable form of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), a soft yet durable commercial plastic used in footwear, floor mats, cushions and memory foam. It is filled with bacterial spores that, when exposed to nutrients present in compost, germinate and break down the material at the end of its life cycle.

The work is detailed in a paper published on April 30 in Nature Communications.

The biodegradable TPU was made with bacterial spores from a strain of Bacillus subtilis that has the ability to break down plastic polymer materials.