Free study materials from MIT OpenCourseWare enabled 16-year-old Vivan Mirchandani’s nontraditional learning path, opening up scientific research and academic opportunities.

Category: materials – Page 11

A skeleton and a shell? Ancient fossil finally finds home on the tree of life

Skeleton season may be just around the corner, but the skeleton age dawned with the early Cambrian Period, about 538 million to 506 million years ago.

In this time span, most major animal groups independently evolved methods to build mineral skeletons or shells, usually in one of two ways: They either built up mineral tissues using organic scaffolding, like how we grow our bones and teeth, or they gathered materials from their environment and “glued” them together in a protective coating.

Then they stuck with that technique for the next 540 million-plus years. One notable exception can be found in the fossilized remains of Salterella, a tiny creature that thrived in the early Cambrian and is so common in rocks from that time that paleontologists use it as an index fossil to orient themselves in time.

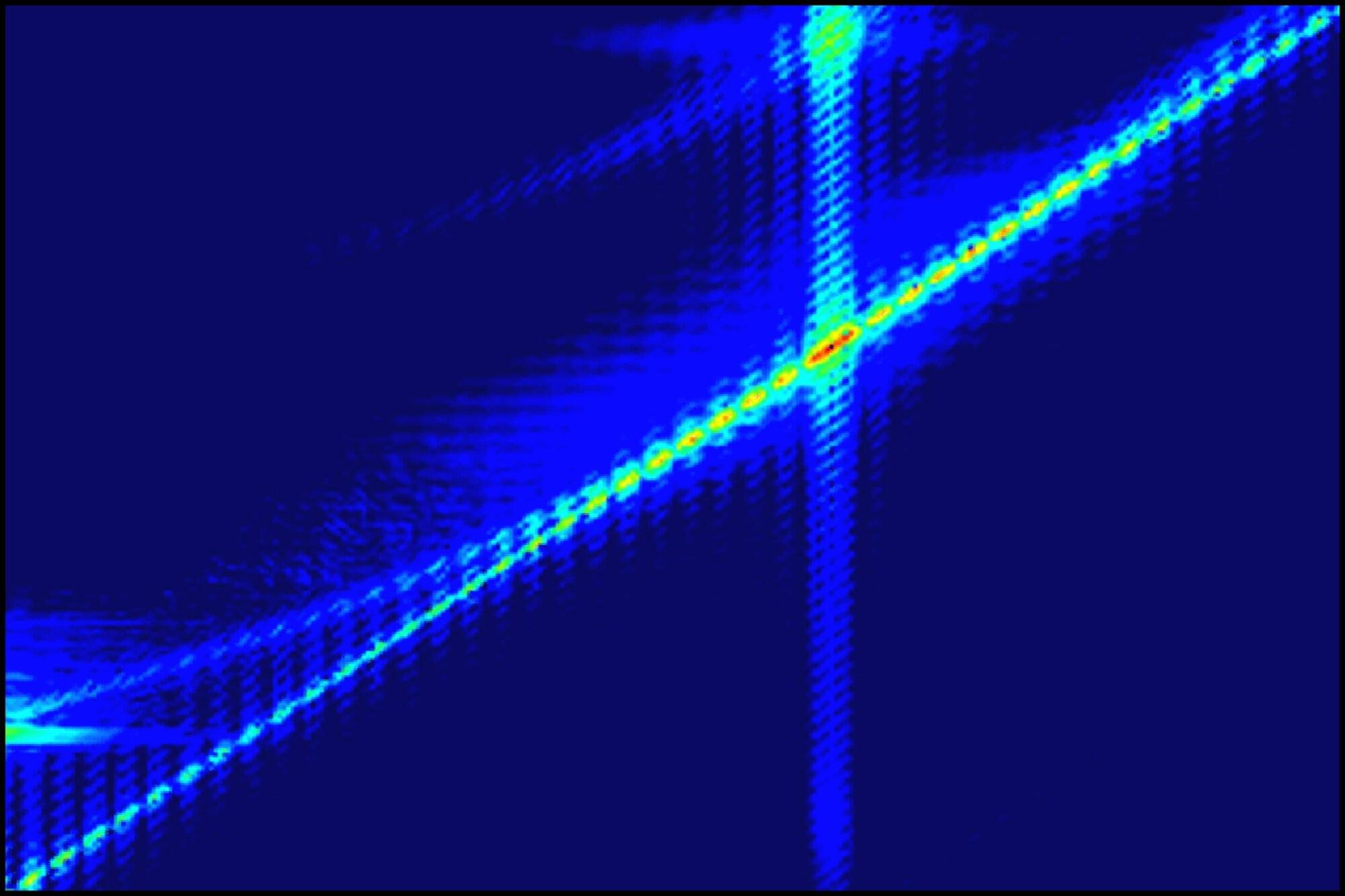

Record spin waves thanks to flux quanta

Spin waves are considered to be promising candidates for a new form of electronics. Instead of electrons, the focus here is on magnons. These quantized units of spin waves describe how spin precession propagates. Similar to electrons, magnons can transmit information in a conductor. However, they do so with much lower resistance and thus a fraction of the energy consumption.

At TU Braunschweig, the Cryogenic Quantum Electronics working group, together with international partners, has now set a new record for the wavelength of excited propagating magnons. The researchers led by Professor Oleksandr Dobrovolskiy used another quasiparticle, fluxons, to excite the spin waves. The team collaborated with partners from Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China, Goethe University Frankfurt am Main, the University of Vienna and the University of Bordeaux.

“Fluxons move as magnetic flux quanta of a superconductor at speeds of up to 10 kilometers per second. We succeeded in using the ultra-fast fluxons to excite a spin wave in a neighboring magnet,” explains Dobrovolskiy. “This effect can be imagined as similar to the bow wave created by a speedboat in water. Except that our boat is so fast that it literally creates a kind of sonic boom.”

Checking the quality of materials just got easier with a new AI tool

Manufacturing better batteries, faster electronics, and more effective pharmaceuticals depends on the discovery of new materials and the verification of their quality. Artificial intelligence is helping with the former, with tools that comb through catalogs of materials to quickly tag promising candidates.

But once a material is made, verifying its quality still involves scanning it with specialized instruments to validate its performance — an expensive and time-consuming step that can hold up the development and distribution of new technologies.

Now, a new AI tool developed by MIT engineers could help clear the quality-control bottleneck, offering a faster and cheaper option for certain materials-driven industries.

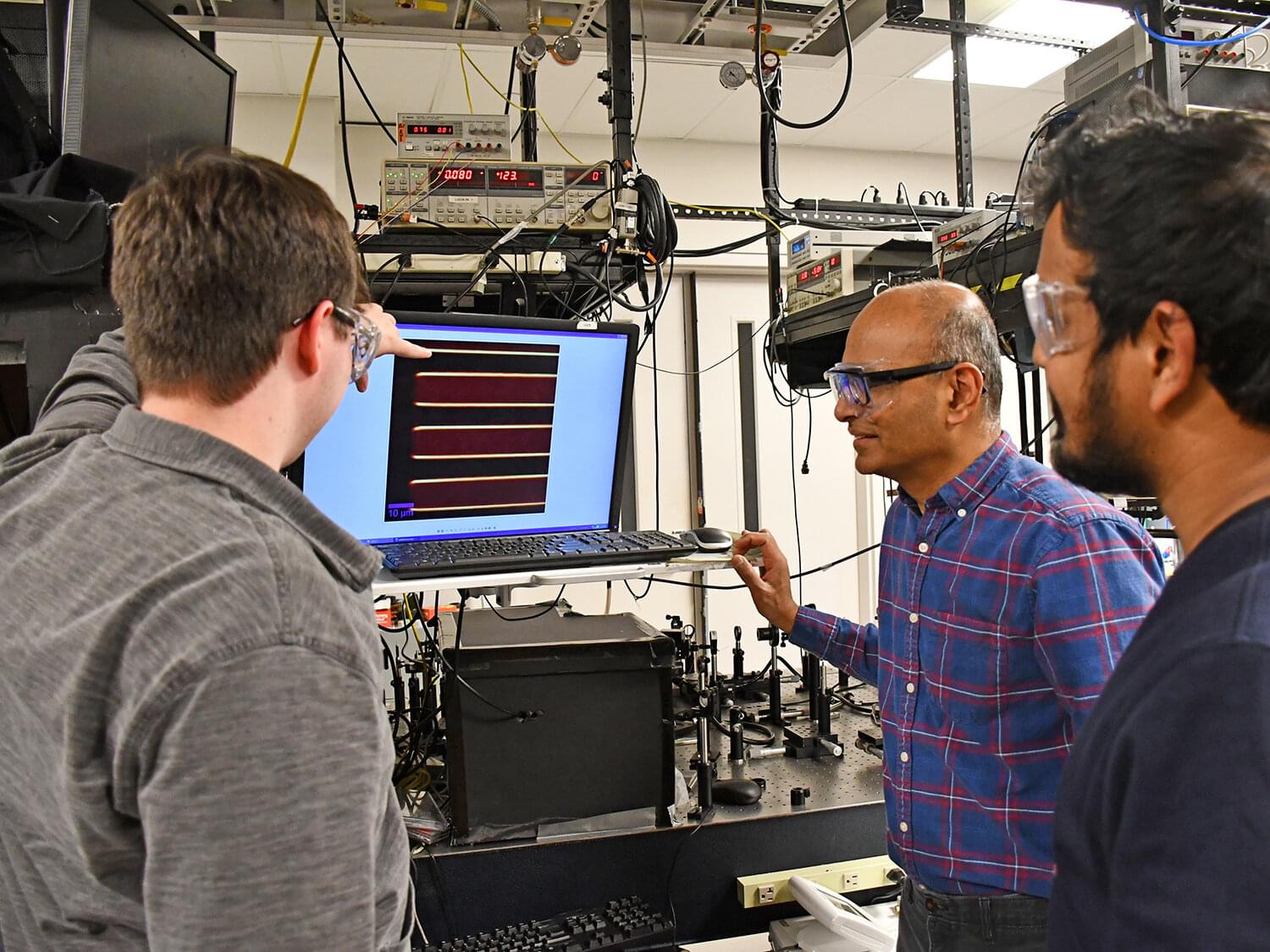

Framework models light-matter interactions in nonlinear optical microscopy to determine atomic structure

Materials scientists can learn a lot about a sample material by shooting lasers at it. With nonlinear optical microscopy—a specialized imaging technique that looks for a change in the color of intense laser light—researchers can collect data on how the light interacts with the sample, and through time-consuming and sometimes expensive analyses, characterize the material’s structure and other properties.

Now, researchers at Pennsylvania State University have developed a computational framework that can interpret the nonlinear optical microscopy images to characterize the material in microscopic detail.

The team has published its approach in the journal Optica.

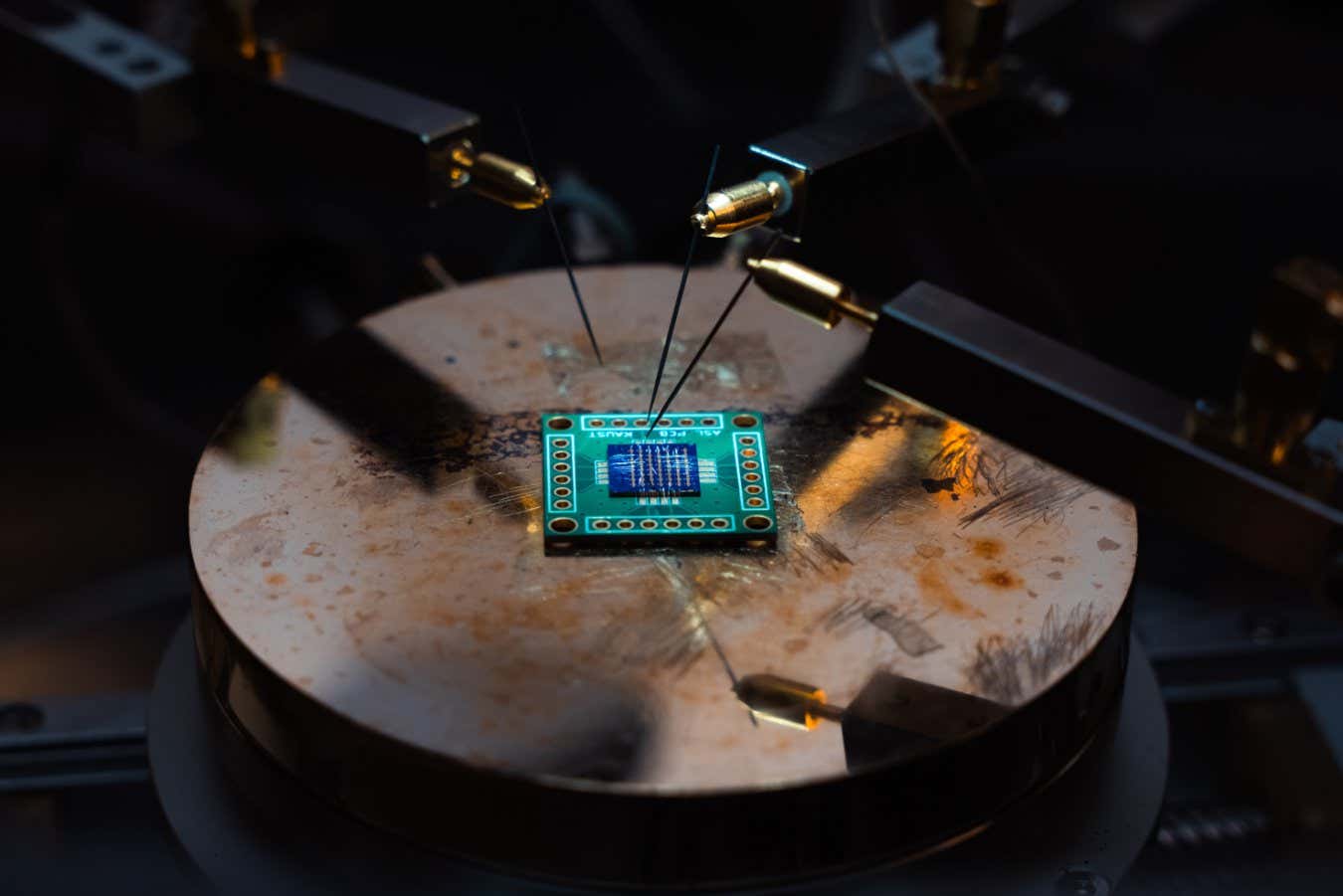

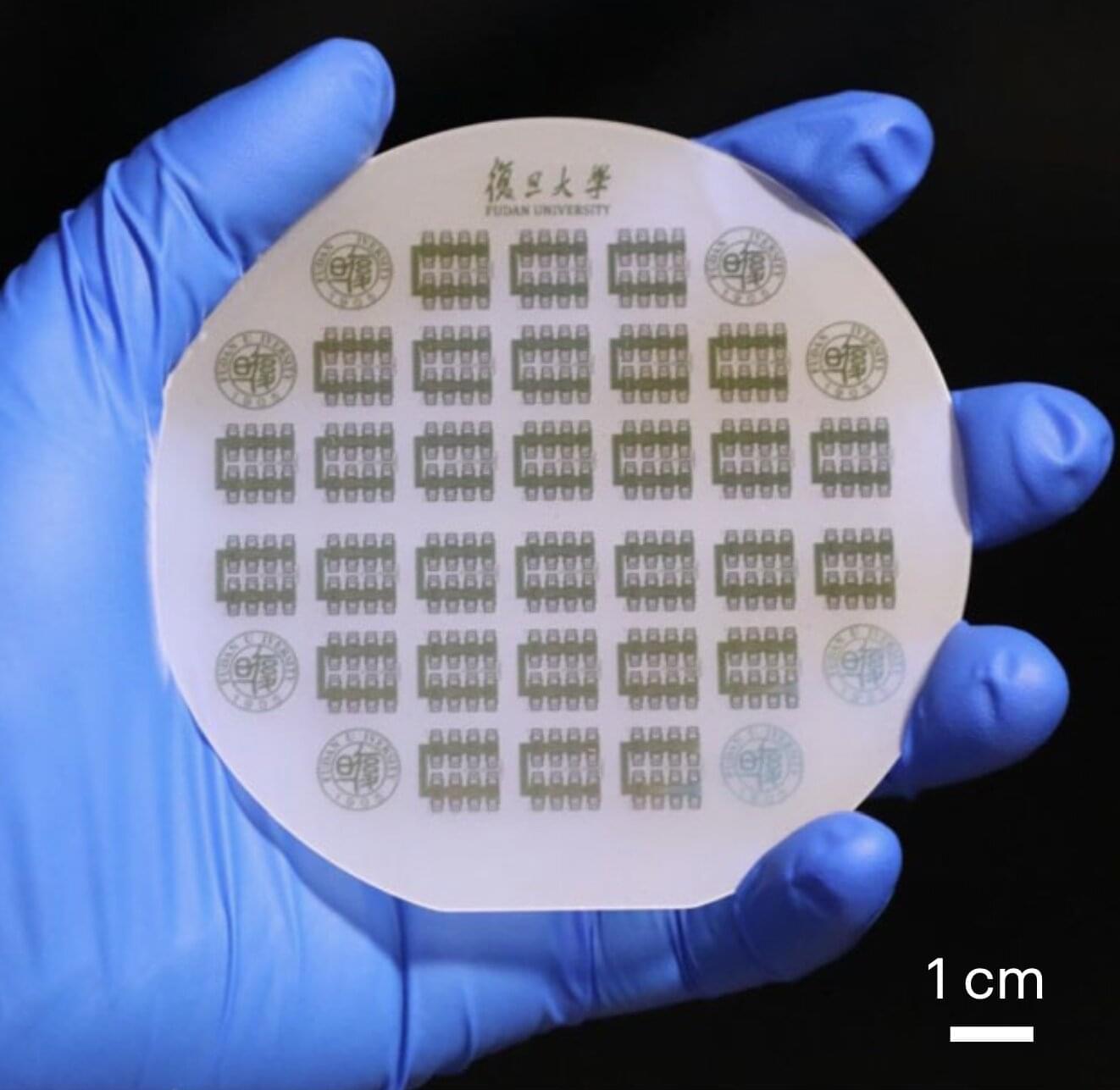

Low-power MoS₂-based microwave transmitter could advance communications

To further advance wireless communication systems, electronics engineers have been trying to develop new electronic circuits that operate in the microwave frequency range (1–300 GHz), while also losing little energy while transmitting signals. Ideally, these circuits should also be more compact than existing solutions, as this would help to reduce the overall size of communication systems.

Most of the microwaves integrated in current communication systems are made of bulk materials, such as silicon or gallium arsenide. While these circuits have achieved good results so far, both their size and power consumption have proved to be difficult to reduce further.

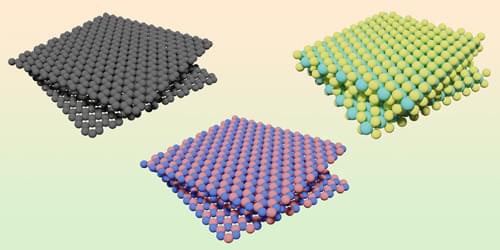

Two-dimensional (2D) semiconducting materials, which are made up of a single atomic layer, could overcome the limitations of bulk materials, as they are both thinner and exhibit advantageous electrical properties. Among these materials, molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), has been found to be particularly promising for the development of microwave circuits and other components for communication systems.

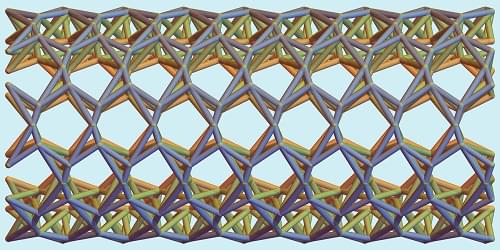

Twisting sound: Scientists discover a new way to control mechanical vibrations in metamaterial

Scientists at the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center (CUNY ASRC) have discovered a way to control sound and vibrations using a concept inspired by “twistronics,” a phenomenon originally developed for electronics.

Their research, published in the journal PNAS, introduces “twistelastics”—a technique that uses tiny rotations between layers of engineered surfaces to manipulate how mechanical waves travel.

Sound and vibration control are essential for technologies like ultrasound imaging, microelectronics, and advanced sensors. Traditionally, these systems rely on fixed designs, limiting flexibility. The new approach allows engineers to reconfigure wave behavior by twisting two layers of engineered surfaces, enabling unprecedented adaptability.