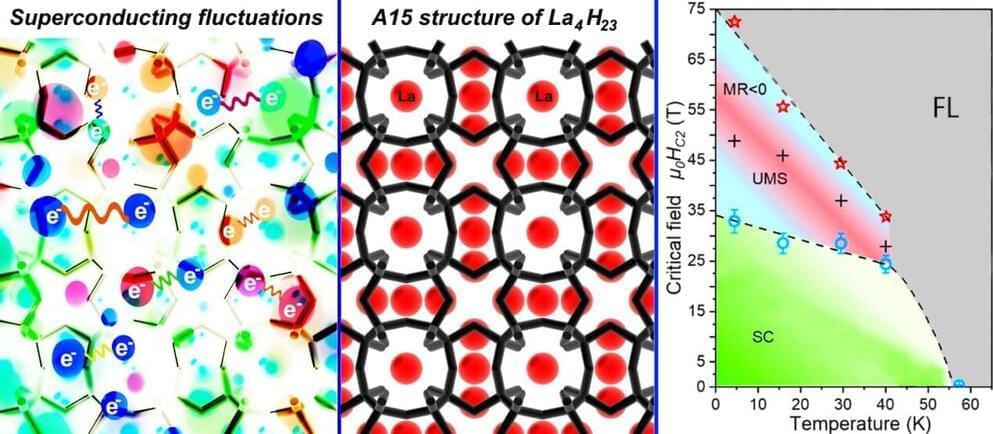

Researchers from Skoltech, Jilin University and Beijing HPSTAR in China, and their German colleagues have synthesized and studied a new type of hydrogen-rich superconductor. Technically referred to as an A15-type lanthanum superhydride, with the formula La4H23, it shows superconductivity below minus 168 degrees Celsius at a pressure of 1.2 million atmospheres. The research results were published in the National Science Review.

Polyhydrides are a novel class of compounds synthesized at about 1 million times the normal atmospheric pressure on Earth. They can exhibit unique superconducting properties with record-high critical temperatures of up to-23 C in lanthanum decahydride LaH10, critical magnetic fields reaching 300 tesla, and critical current densities.

Even compared to other similar hydrides, the newly discovered La4H23 behaves unusually: It has a negative temperature coefficient of electrical resistance in a certain pressure range. That is, unlike ordinary metals, with a decrease in temperature its electrical resistance does not decrease but grows, the way it happens in semiconductors and many unconventional superconductors, such as cuprates.