What does it take to turn bold ideas into life-saving medicine?

In this episode of The Big Question, we sit down with @MIT’s Dr. Robert Langer, one of the founding figures of bioengineering and among the most cited scientists in the world, to explore how engineering has reshaped modern healthcare. From early failures and rejected grants to breakthroughs that changed medicine, Langer reflects on a career built around persistence and problem-solving. His work helped lay the foundation for technologies that deliver large biological molecules, like proteins and RNA, into the body, a challenge once thought impossible. Those advances now underpin everything from targeted cancer therapies to the mRNA vaccines that transformed the COVID-19 response.

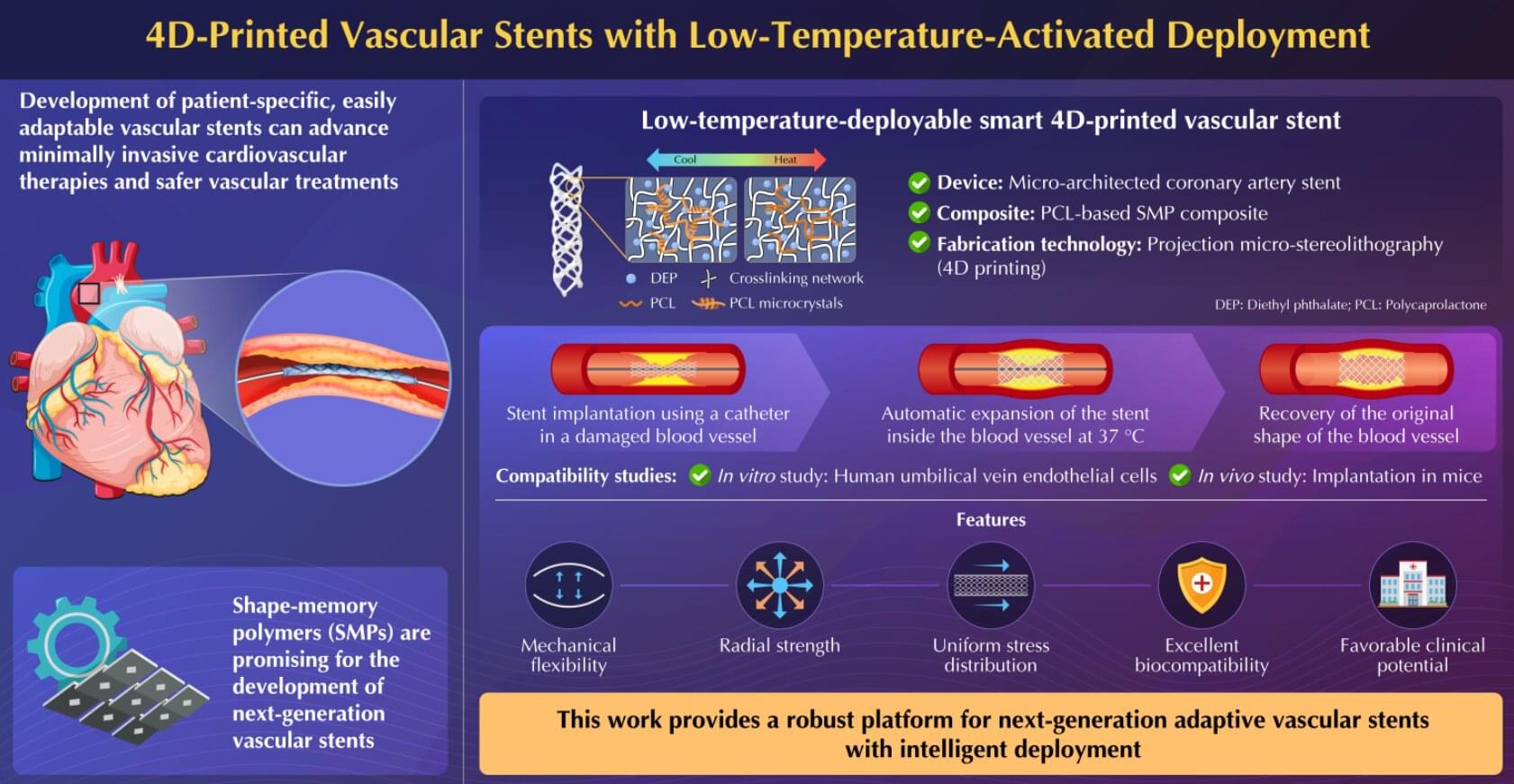

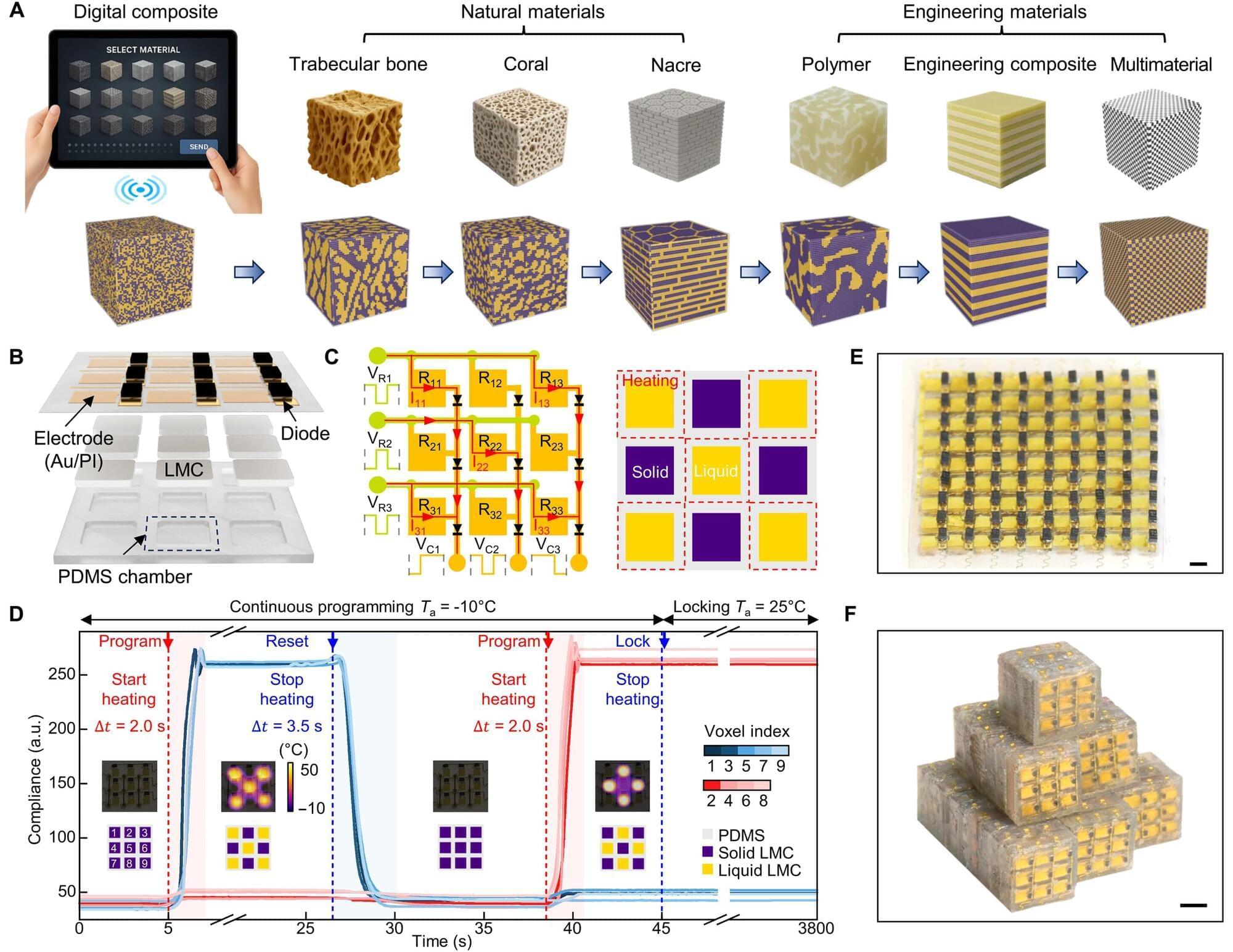

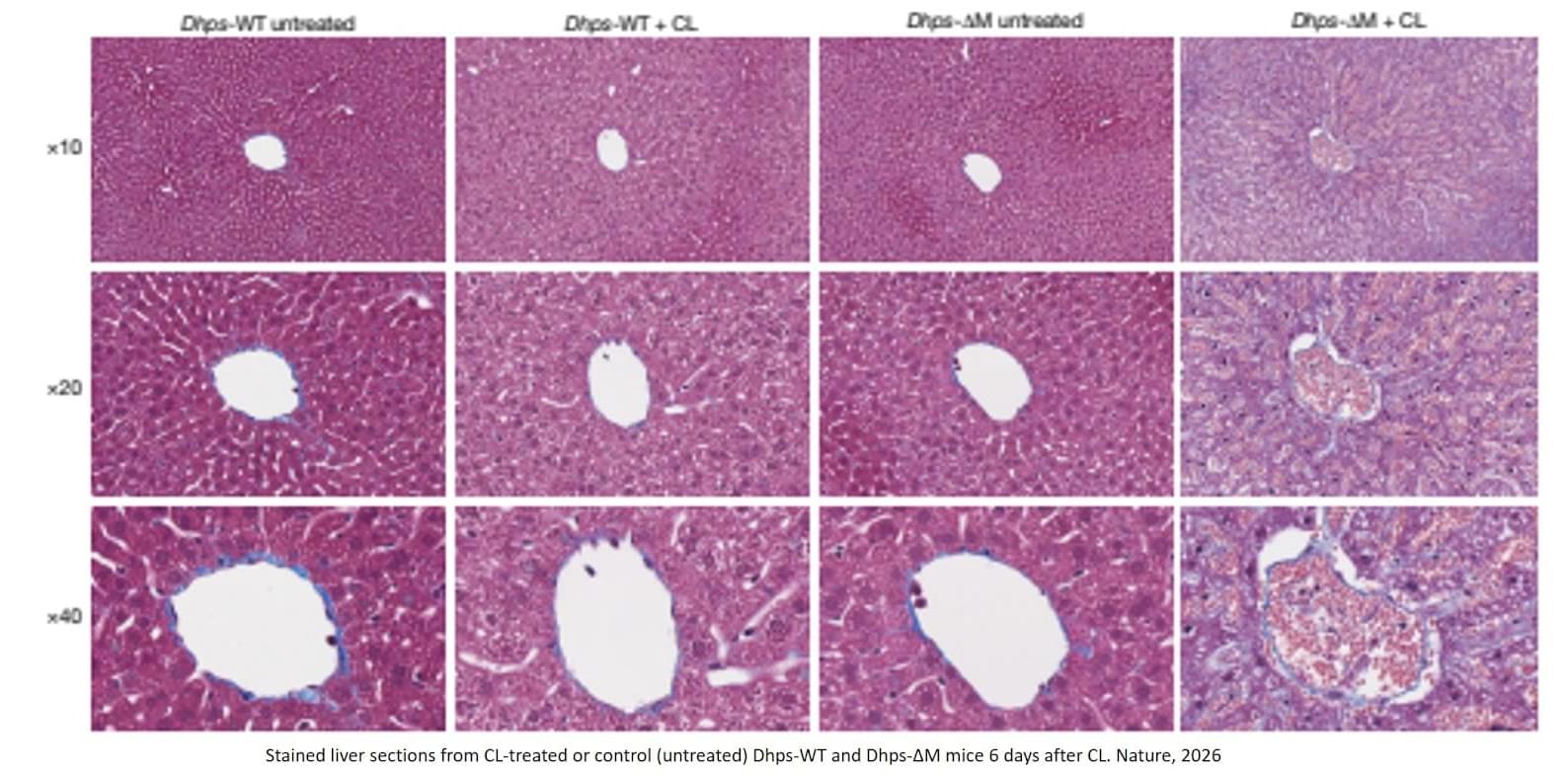

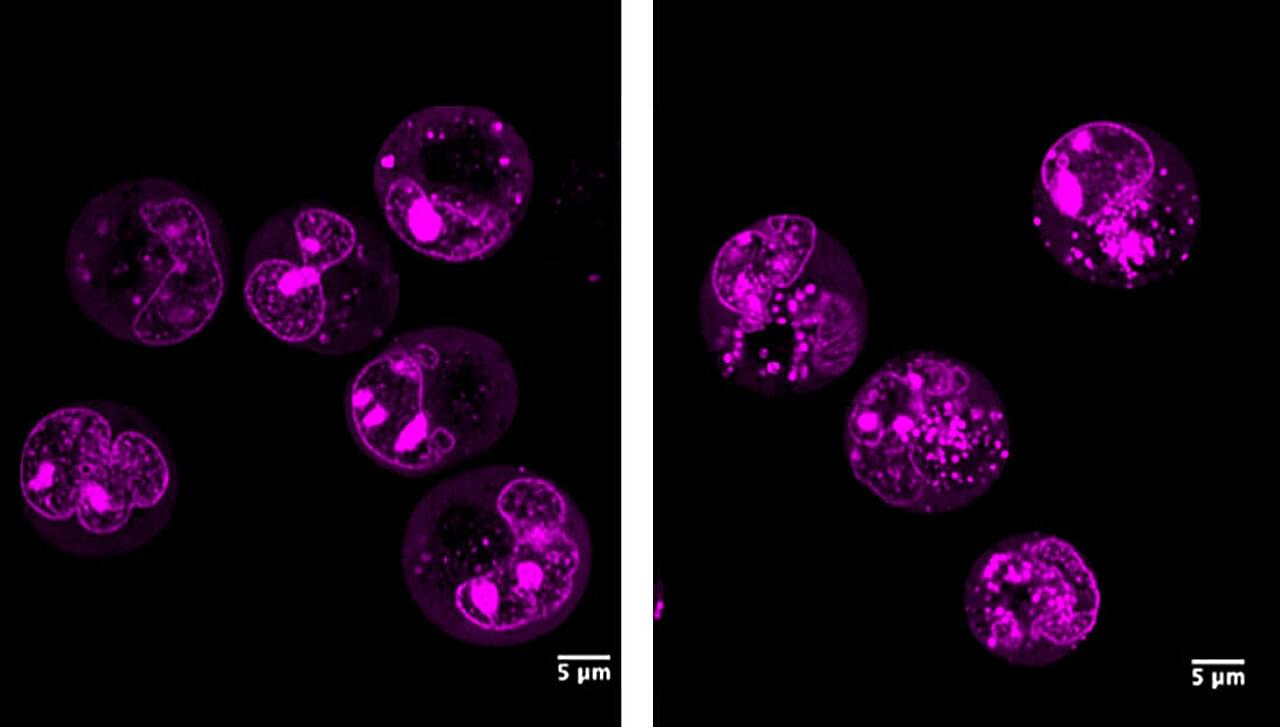

The conversation looks forward as well as back, diving into the future of medicine through engineered solutions such as artificial skin for burn victims, FDA-approved synthetic blood vessels, and organs-on-chips that mimic human biology to speed up drug testing while reducing reliance on animal models. Langer explains how nanoparticles safely carry genetic instructions into cells, how mRNA vaccines train the immune system without altering DNA, and why engineering delivery, getting the right treatment to the right place in the body, remains one of medicine’s biggest challenges. From personalized cancer vaccines to tissue engineering and rapid drug development, this episode reveals how science, persistence, and engineering come together to push the boundaries of what medicine can do next.

#Science #Medicine #Biotech #Health #LifeSciences.

Chapters:

00:00 Engineering the Future of Medicine.

01:55 Failure, Persistence, and Scientific Breakthroughs.

05:30 From Chemical Engineering to Patient Care.

08:40 Solving the Drug Delivery Problem.

11:20 Delivering Proteins, RNA, and DNA

14:10 The Origins of mRNA Technology.

17:30 How mRNA Vaccines Work.

20:40 Speed and Scale in Vaccine Development.

23:30 What mRNA Makes Possible Next.

26:10 Trust, Misinformation, and Vaccine Science.

28:50 Engineering Tissues and Organs.

31:20 Artificial Skin and Synthetic Blood Vessels.

33:40 Organs on Chips and Drug Testing.

36:10 Why Science Always Moves Forward.

The Big Question with the Museum of Science: