News, analysis and opinion from the Financial Times on the latest in markets, economics and politics.

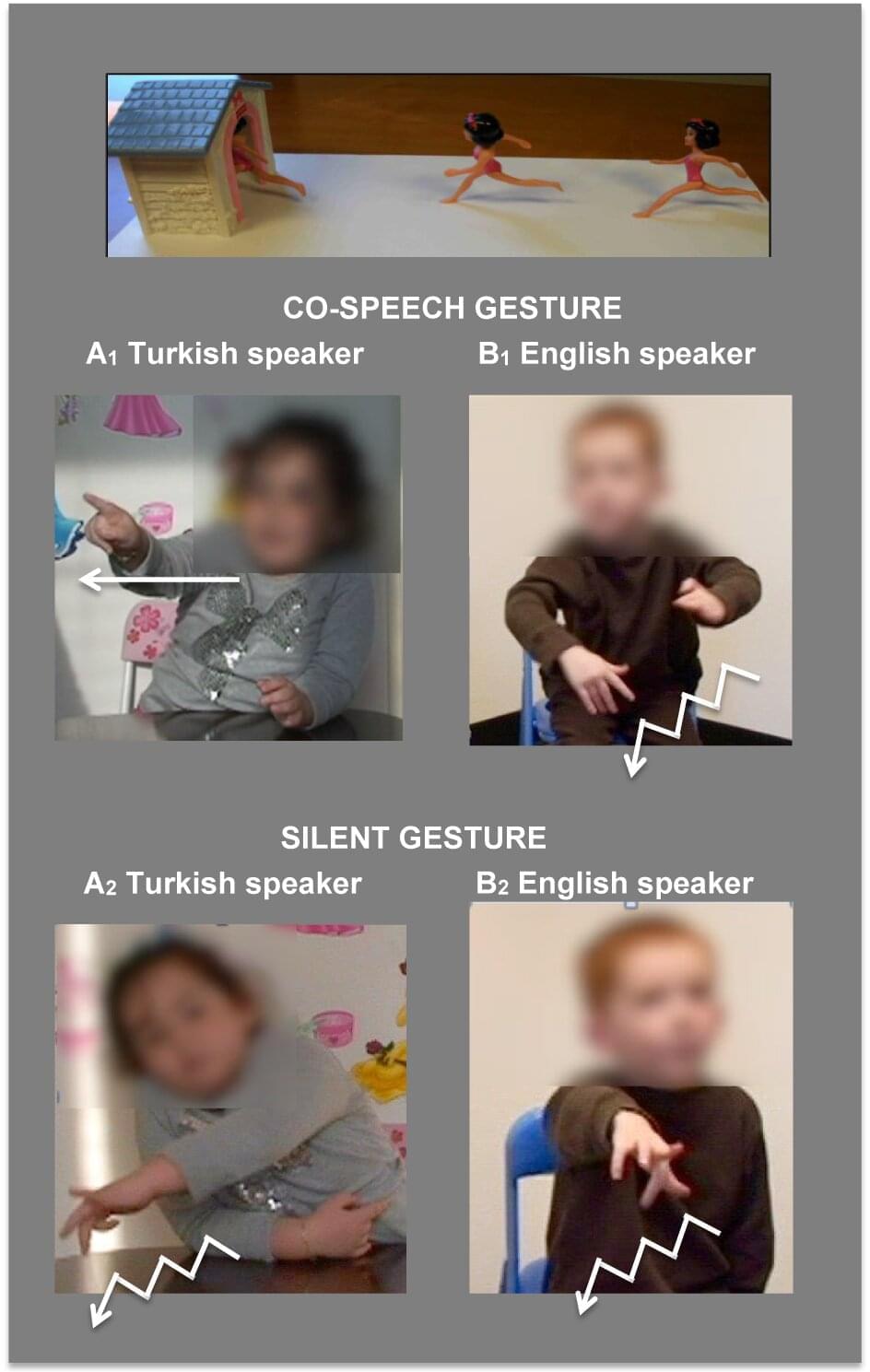

Recent research conducted at Georgia State University shows that native language affects how people convey information from a young age and hints at the presence of a universal system of communication.

Şeyda Özçalışkan, a professor in the Psychology Department, has been researching the connection between language and thought for years. Her latest study, “What the development of gesture with and without speech can tell us about the effect of language on thought,” published in Language and Cognition, is a continuation of previous work with adults.

For this study, Özçalışkan, in collaboration with Susan Goldin-Meadow at the University of Chicago and Che Lucero at Cornell University, focused on children ages 3 to 12. The children either spoke English or Turkish. They were asked to use their hands to act out specific actions, such as running into a house.

Severe solar storms are estimated to affect Earth every 150 years, and they pose a threat to power grids and other infrastructure. Scientists are building new models and working with industries to avoid a worst-case scenario. Illustration: Michael Tabb.

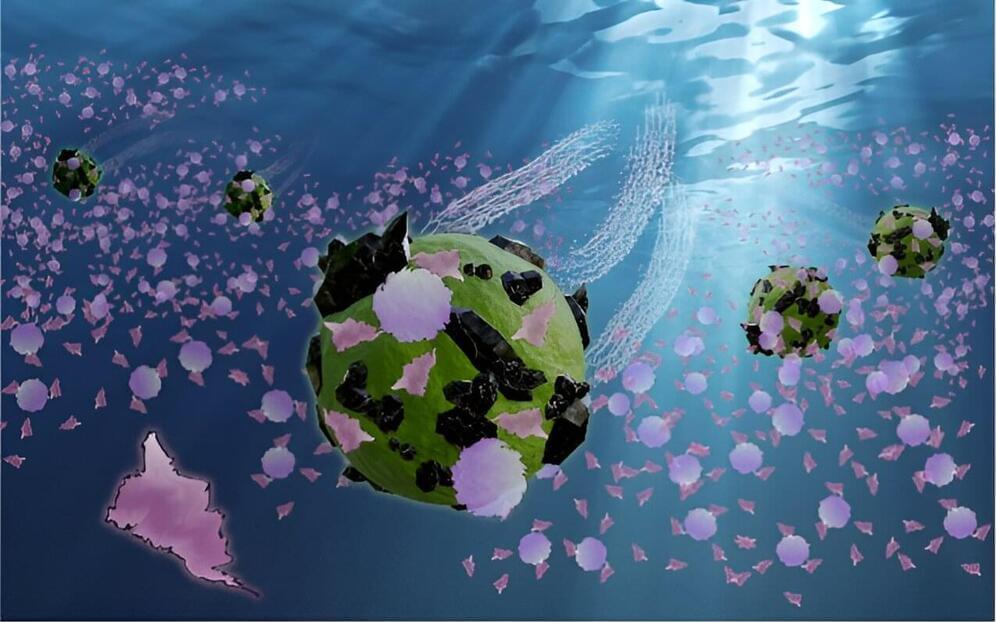

Seas, oceans, rivers, and other bodies of water on Earth have become increasingly polluted over the past decades, and this is threatening the survival of many aquatic species. This pollution takes a wide range of forms, including the proliferation of so-called micro and nano plastics.

As suggested by their name, micro and nano plastics are harmful tiny particles derived from the disintegration of plastic waste released into the water. These particles have been found to disrupt aquatic ecosystems, for instance, delaying the growth of organisms, reducing their food intake, and damaging fish habitats.

Devising effective technologies to effectively remove these tiny particles is of utmost importance, as it could help to protect endangered species and their natural environments. These technologies should be carefully designed to prevent further pollution and destruction; thus, they should be based on environmentally friendly materials.

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Ecologists from Mexico’s National Autonomous university on Friday relaunched a fundraising campaign to bolster conservation efforts for axolotls, an iconic, endangered fish-like type of salamander.

The campaign, called “Adoptaxolotl,” asks people for as little as 600 pesos (about $35) to virtually adopt one of the tiny “water monsters.” Virtual adoption comes with live updates on your axolotl’s health. For less, donors can buy one of the creatures a virtual dinner.

In their main habitat the population density of Mexican axolotls (ah-ho-LOH’-tulz) has plummeted 99.5% in under two decades, according to scientists behind the fundraiser.

Architect Tariq Khayyat has designed The Fold, a sculptural housing development in Dubai that features curved facades and aims to create a “communal oasis” behind a main road.

The Fold, which comprises 28 terraced townhouses, is located along the large Al Wasl Road in Dubai’s Jumeirah district and was designed to have a more organic feel than neighbouring developments.

“We wanted to plant a tulip field on the Al Wasl Road,” Tariq Khayyat Design Partners founder Khayyat told Dezeen.

OpenAI co-founder and president Greg Brockman has quit the firm, he said Friday, hours after the Microsoft-backed giant abruptly fired its chief executive Sam Altman and assured that Brockman would remain at the startup. Brockman’s sudden departure adds to the day’s uncertainties at OpenAI, following closely on the heels of its maiden developer conference led by Altman.

“I’m super proud of what we’ve all built together since starting in my apartment 8 years ago. We’ve ben through tough & great times together, accomplishing so much despite all the reasons it should have been impossible,” wrote Brockman in a message to OpenAI team. “But based on today’s news, I quit. Genuinely wishing you all nothing but the best. I continue to believe in the mission of creating safe AGI that benefits all of humanity.”

OpenAI earlier said that Brockman was stepping down as chairman of the board, but will remain at the firm. Brockman, who co-founded OpenAI with Altman, is a close confidant of the former OpenAI chief executive.