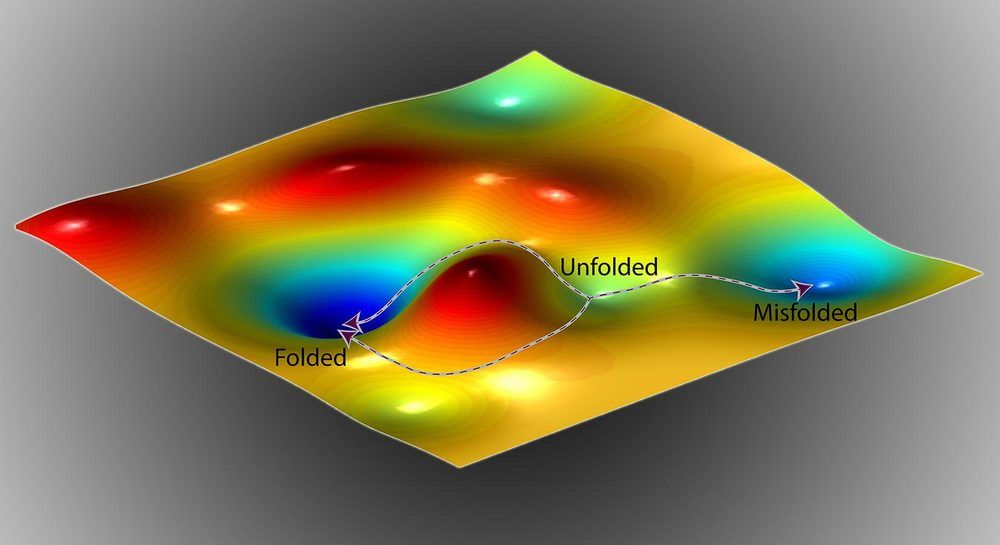

Stem Cell Neurotherapy sends therapeutic messages, e.g., “your stem cells are transforming into new cells for the lungs, liver, and kidneys” to the DNA inside the nucleus of stem cells. Inside the nucleus, the DNA receives the message and transmits it to the RNA, which translates the message into genetic code.

The genes inside the stem cells transmit the coded message to the proteins, which are converted by the mitochondria into ATP, which provides the energy for the coded message to transform the stem cells into a new set of lung cells, as well as new cells for the kidneys and liver.

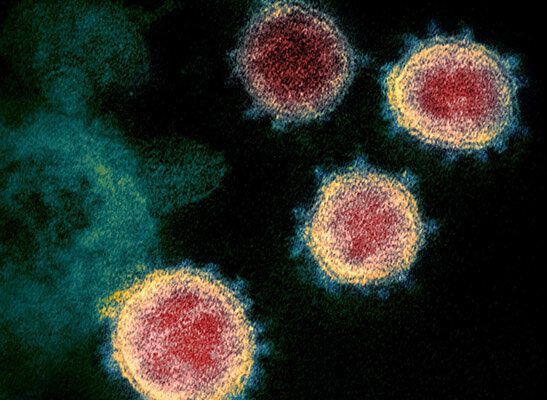

These new cells in the lungs, kidneys, and liver will replace the cells that were infected by the COVID-19 virus. This results in the elimination of the coughing, fever, headaches, diarrhea, and breathing problems.

“If all … went well and it worked well, then I would propose … three months’ time,” she said, when asked how quickly the treatment, which was developed by doctors and researchers at the Abu Dhabi Stem Cell Center, could reach the market.

To date, there are no known vaccines or specific antiviral medicines against Covid-19. U.S. health officials say developing a vaccine will take at least 12 to 18 months.

The UAE has 14,163 cases and 126 deaths due to the coronavirus, based on data from Johns Hopkins University.