The PneumoPlanet inflatable lunar habitat offers an opportunity for future lunar astronauts to comfortably live, eat and work on the moon, its designers say.

Category: food – Page 117

New Smart Technology Developed by UC Davis Professor May Help in Early Detection of Insects in Food and Agricultural Products

Zhongli Pan is the recipient of the 2023 Distinguished Service Award by the Rice Technical Working Group, which will be presented at the 2023 RTWF Conference on February 20–23. The award recognizes individuals who have given distinguished long-term service to the rice industry in areas of research, education, international agriculture, administration and industry rice technology.

Post-harvest losses are common in the global food and agricultural industry. Research shows that storage grain pests can cause serious post-harvest losses, almost 9% in developed countries to 20% or more in developing countries. To address this problem, Zhongli Pan, an adjunct professor in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, has developed a potential solution.

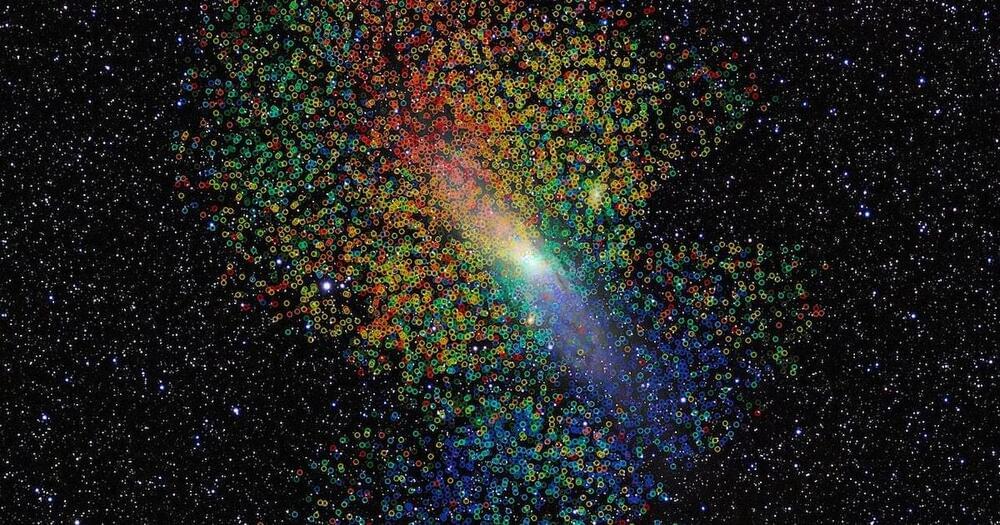

Pan’s recent project using an IoT (Internet of Things) based smart wireless technology to remotely detect early insect activity in storage, processing, handling and transportation may solve the insect infestation related challenges for the agricultural industry. The technology uses a novel device called SmartProbe – designed by Pan and his team using wireless sensors and cameras – and leverages cloud computing to monitor and predict insect occurrences. This could help control insect pest, reduce food loss and the fumigants used in agricultural products today. Ragab Gebreil, a project scientist in Pan’s lab, is the co-inventor of this technology.

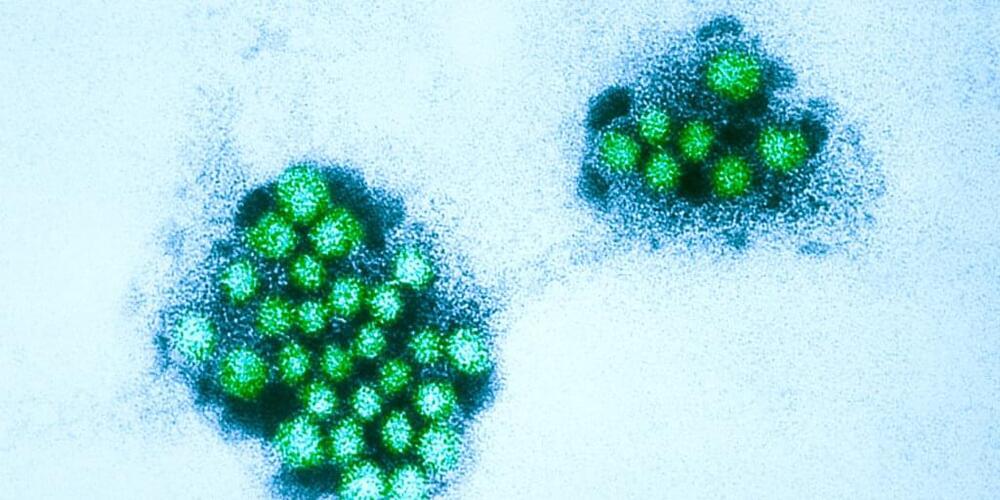

Norovirus appears to be spreading as rate of positive tests spikes

Norovirus is sometimes referred to as the stomach flu, but it is not related to the influenza virus. Rather, it is a highly contagious virus that typically causes gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, vomiting, nausea and stomach pain. Mild fever and aches are possible, too.

Just a few virus particles are enough to make someone sick, and they spread easily via hands, surfaces, food and water. An infected person can transmit the virus for days after they’re feeling better, potentially even up to two weeks, according to the CDC.

Regionally, the Midwest had the highest average test positivity rate for norovirus as of Saturday, at over 19% — higher than any other week in the last year.

Salt Bae is preparing 5,000 hot meals a day for people affected by Turkish earthquake

The Turkish butcher has since shared with fans exactly how he’s going to support those affected by the earthquake. See the food prep here:

Compound in Mushrooms Discovered To Magnify Memory

Researchers from The University of Queensland have discovered the active compound from an edible mushroom that boosts nerve growth and enhances memory.

Professor Frederic Meunier from the Queensland Brain Institute said the team had identified new active compounds from the mushroom, Hericium erinaceus. This type of edible mushroom, commonly known as the Lion’s Mane Mushroom, is native to North America, Europe, and Asia. It is commonly sought after for its unique flavor and texture, and it is also used in traditional Chinese medicine to boost the immune system and improve digestive health.

Researchers have discovered lion’s mane mushrooms improve brain cell growth and memory in pre-clinical trials.

Can trees talk to each other with fungal networks? Study raises doubts

A new literature review of papers on “common mycorrhizal networks” seems to indicate the science behind them is not as strong as once thought.

Akin to the Ents from “The Lord of the Rings,” there is an idea in modern botany that trees can “talk” to one another through a delicate web of fungus filaments that grows underground. The idea is so alluring that it has gained traction in popular culture and has even been termed the “wood-wide network.”

However, according to Justine Karst, associate professor from the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Agricultural, Life, and Environmental Sciences, it could all be nonsense.

Jacquesvandinteren/iStock.

“It’s great that CMN research has sparked interest in forest fungi, but it’s important for the public to understand that many popular ideas are ahead of the science,” says Karst.

Farming robot kills 200,000 weeds per hour with lasers

In 2021, Carbon Robotics unveiled the third-generation of its Autonomous Weeder, a smart farming robot that identifies weeds and then destroys them with high-power lasers. The company now has taken the technology from that robot and built a pull-behind LaserWeeder — and it kills twice as many weeds.

The weedkiller challenge: Weeds compete with plants for space, sunlight, and soil nutrients. They can also make it easier for insect pests to harm crops, so weed control is a top concern for farmers.

Chemical herbicides can kill the pesky plants, but they can also contaminate water and affect soil health. Weeds can be pulled out by hand, but it’s unpleasant work, and labor shortages are already a huge problem in the agriculture industry.