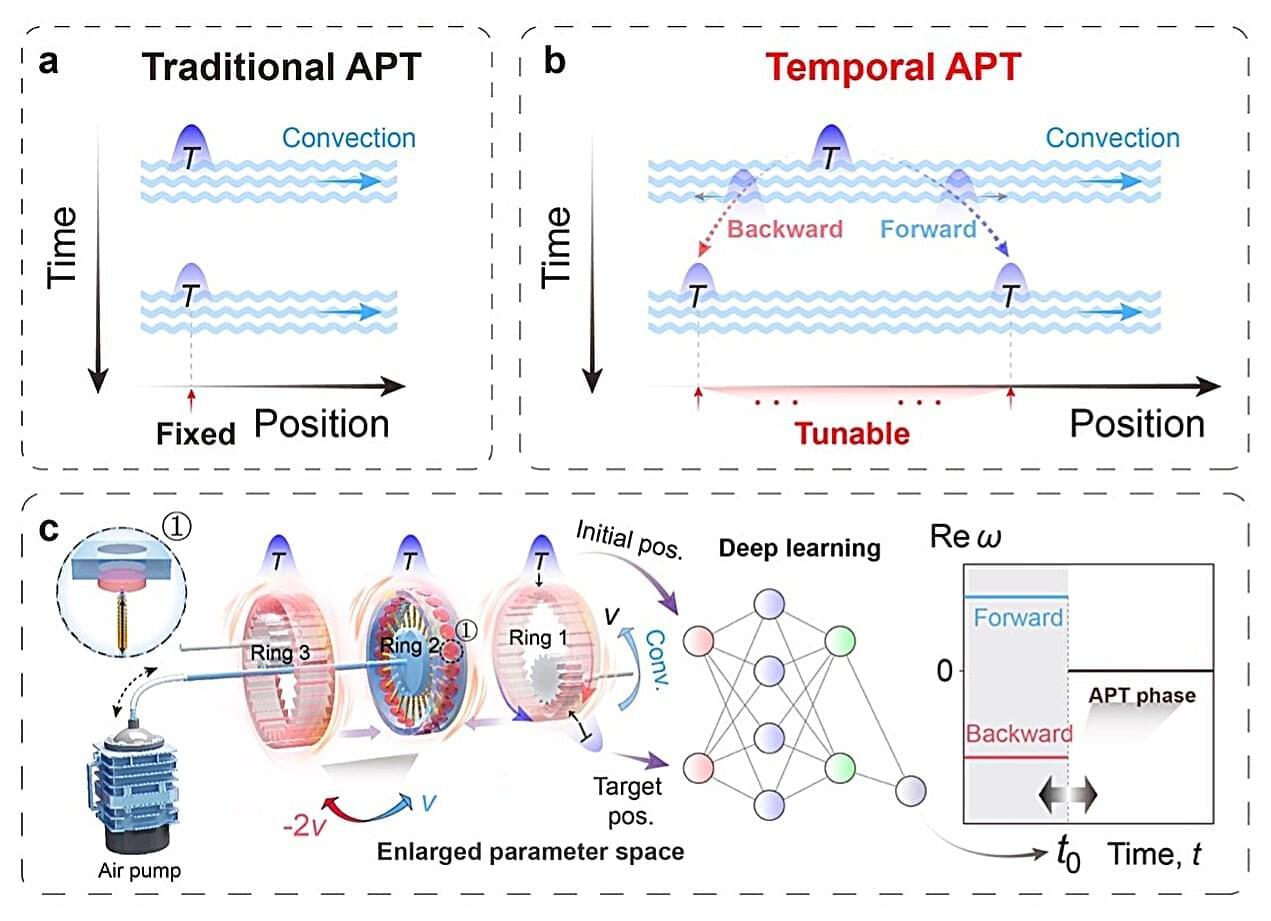

The movement of waves, patterns that carry sound, light or heat, through materials has been widely studied by physicists, as it has implications for the development of numerous modern technologies. In several materials, the movement of waves depends on a physical property known as parity-time (PT) symmetry, which combines mirror-like spatial symmetry with a symmetry in a system’s behavior when time runs forward and backwards.

Systems with PT symmetry can suddenly alter their behavior when they pass specific thresholds known as phase transitions, where they shift from balanced to unbalanced states. So far, systems exhibiting PT symmetry are mostly static, meaning that they exhibit fixed properties over time.

In Nature Physics, researchers at University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Fudan University and National University of Singapore introduce a new concept called temporal anti-parity–time (APT) symmetry, which delineates more clearly both where and when a phase transition happens in a non-Hermitian system, a system that exchanges energy with its surroundings.