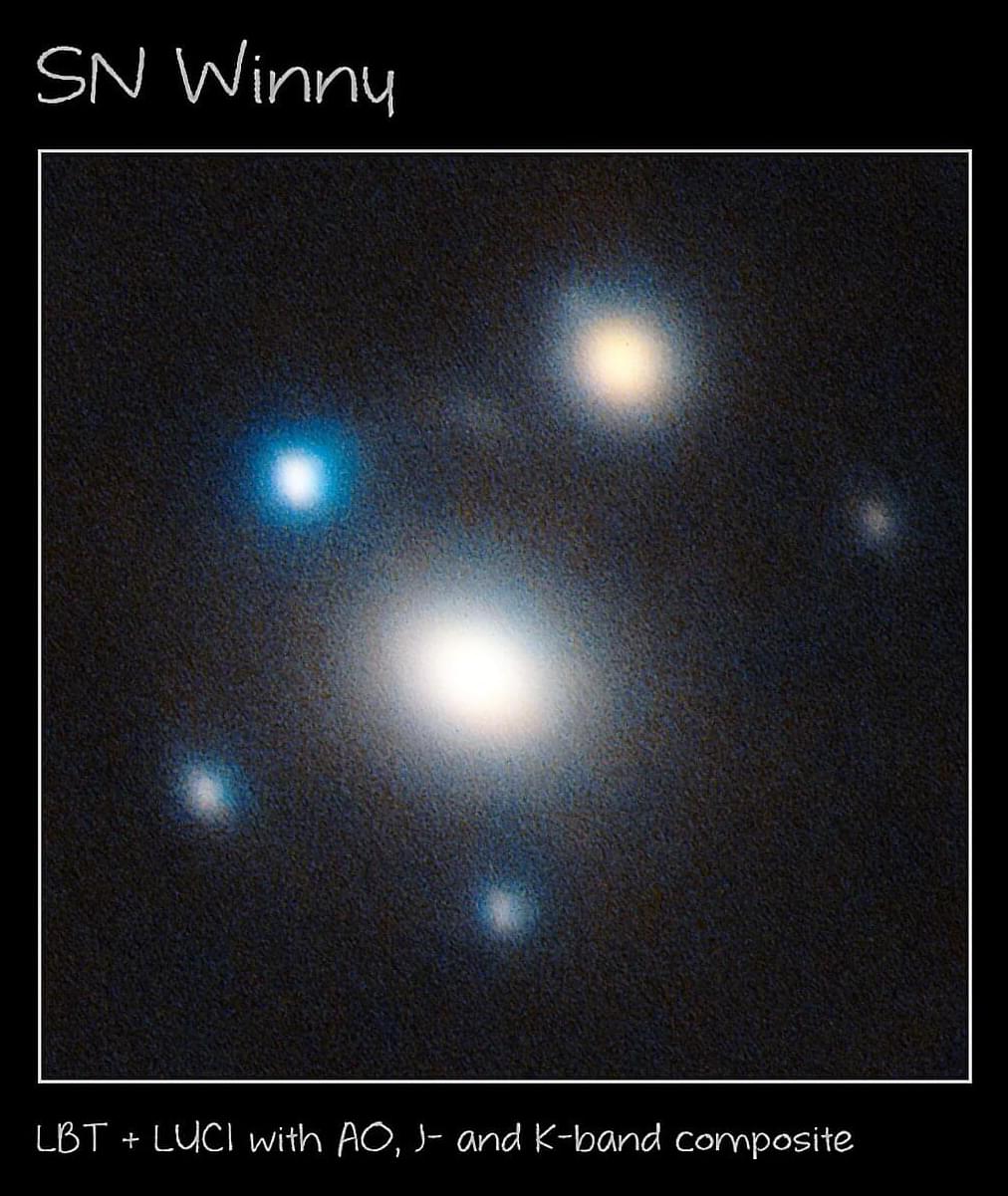

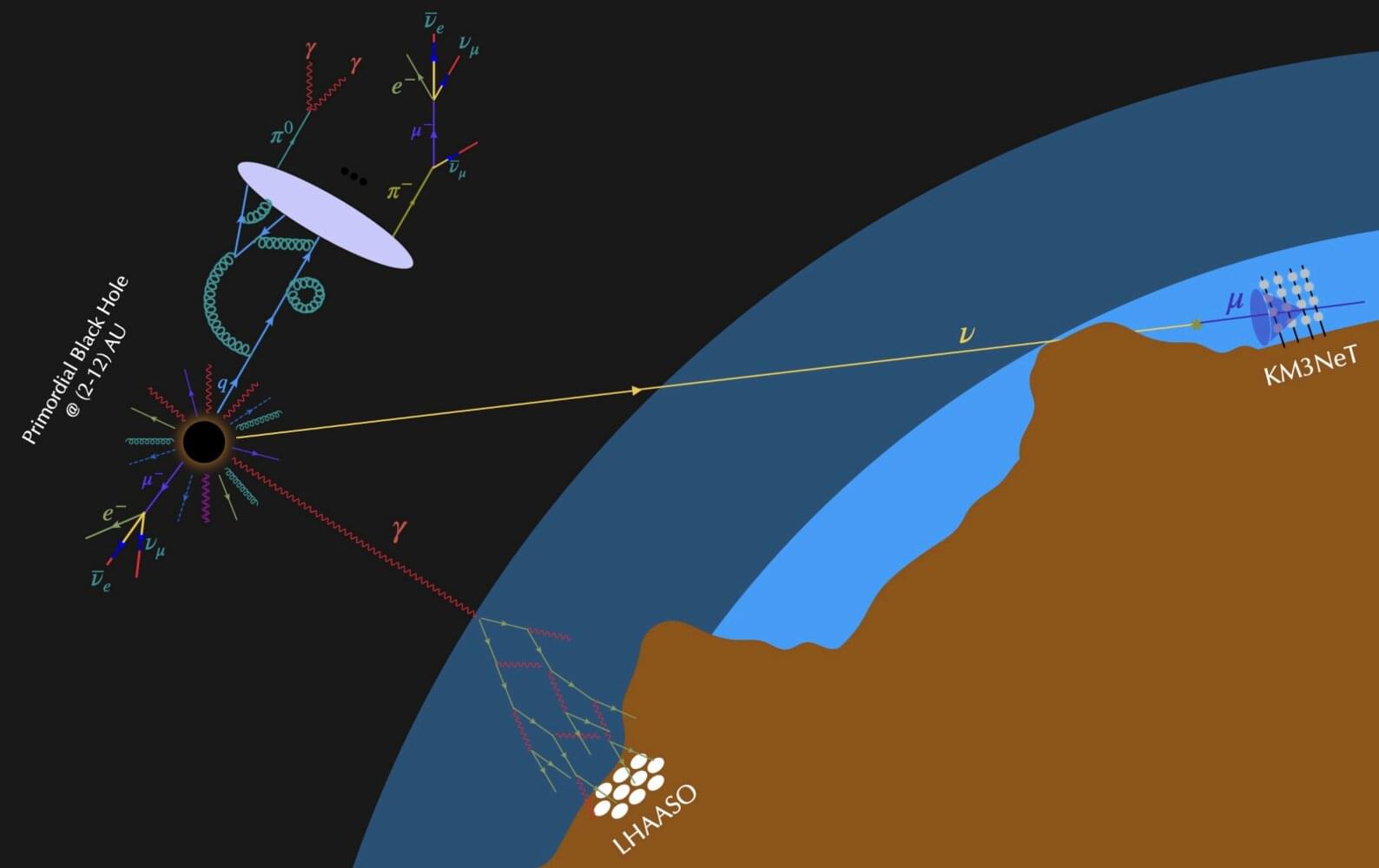

Neutron stars are ultra-dense remnants of massive stars that collapsed after supernova explosions and are made up mostly of subatomic particles with no electric charge (i.e., neutrons). When two neutron stars collide, they are predicted to produce gravitational waves, ripples in the fabric of spacetime that travel at the speed of light.

Gravitational waves typically take the form of oscillations, periodically and temporarily influencing the universe’s underlying fabric (i.e., spacetime). However, general relativity suggests that for some cosmological events, in addition to the oscillatory displacement of test masses (as produced by the passage of a gravitational wave train), there exists a final permanent displacement of them via a phenomenon referred to as “gravitational wave memory.”

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the Academy of Athens, the University of Valencia and Montclair State University recently carried out a study exploring the gravitational wave memory effects that would arise from neutron star mergers.