Category: cosmology – Page 392

How (Relatively) Simple Symmetries Underlie Our Expanding Universe

Isaac Newton and other premodern physicists saw space and time as separate, absolute entities — the rigid backdrops against which we move. On the surface, this made the mathematics behind Newton’s 1687 laws of motion look simple. He defined the relationship between force, mass and acceleration, for example, as $latex \vec{F} = m \vec{a}$.

In contrast, when Albert Einstein revealed that space and time are not absolute but relative, the math seemed to get harder. Force, in relativistic terms, is defined by the equation $latex \vec {F} =\gamma (\vec {v})^{3}m_{0}\,\vec {a} _{\parallel }+\gamma (\vec {v})m_{0}\,\vec {a} _{\perp }$.

But in a deeper sense, in the ways that truly matter to our fundamental understanding of the universe, Einstein’s theory represented a major simplification of the underlying math.

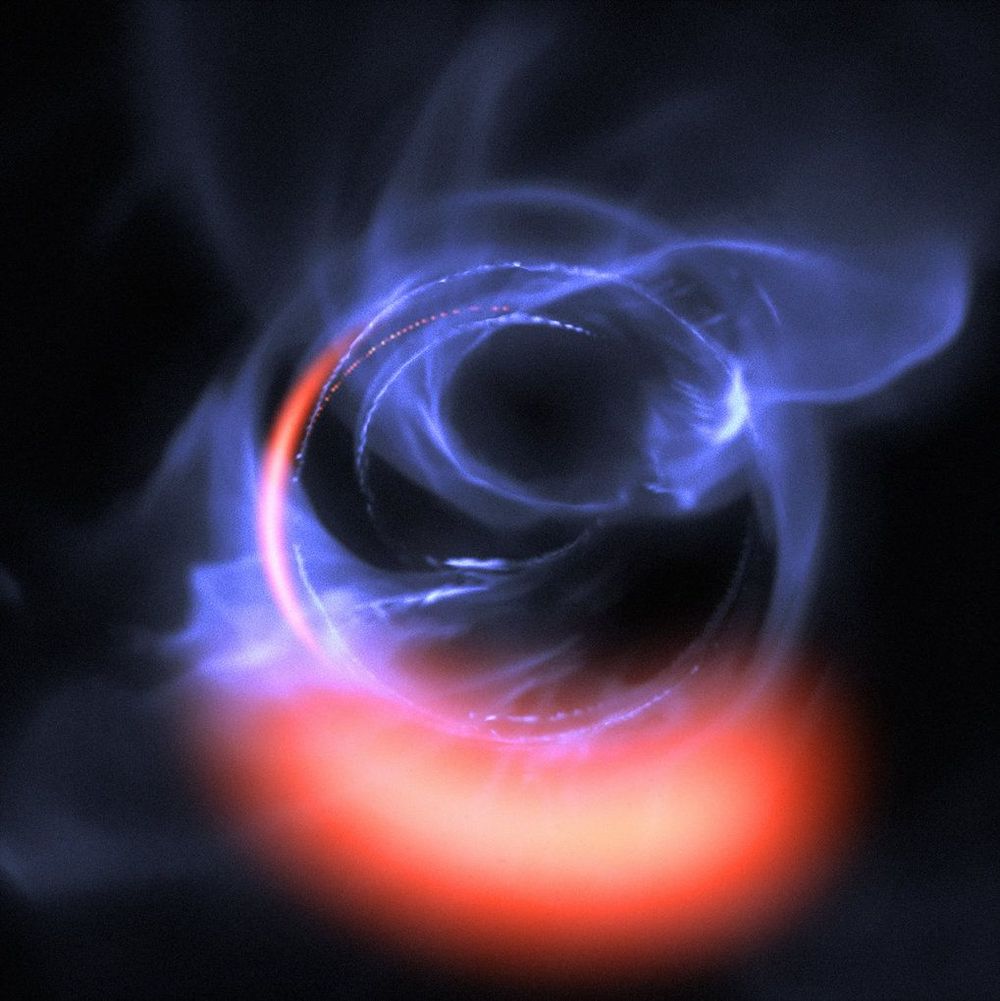

At the edge of the galactic black hole

A team of researchers – including the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching – have gained astounding insights into the galactic centre: The astronomers have spotted gaseous clouds which are spinning around the assumed black hole at the heart of the Milky Way at a speed of around 30 percent of the speed of light. The gas is moving in a circular orbit outside the innermost stable path and can be identified through radiation bursts in the infrared range. This discovery was made possible by the Gravity Instrument, which combines the light of all four eight-metre mirrors of the Very Large Telescope at the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Thanks to this technology, which is called interferometry, Gravity generates the power of a virtual telescope with an effective diameter of 130 metres.

This unusually compact object sits right in the middle of the Milky Way and generates radio emissions: Astronomers call it Sagittarius A*. It is highly probable that this is a black hole with the mass of approx. four million suns. But this is by no means certain, and scientists are always devising new tests to support this thesis. Researchers have now used the Gravity Instrument to take a close look at the edges of the alleged black hole.

According to this theory, the electrons in the gas approaching the event horizon should speed up and therefore increase in brightness. The region of only a few light hours around the black hole is very chaotic, in a similar way to thunderstorms on Earth or radiation bursts on the Sun. Magnetic fields also play a part here, because the gas conducts electricity making it a plasma. The latter should ultimately show up as a flickering “hot spot” circling the black hole on the final stable path.

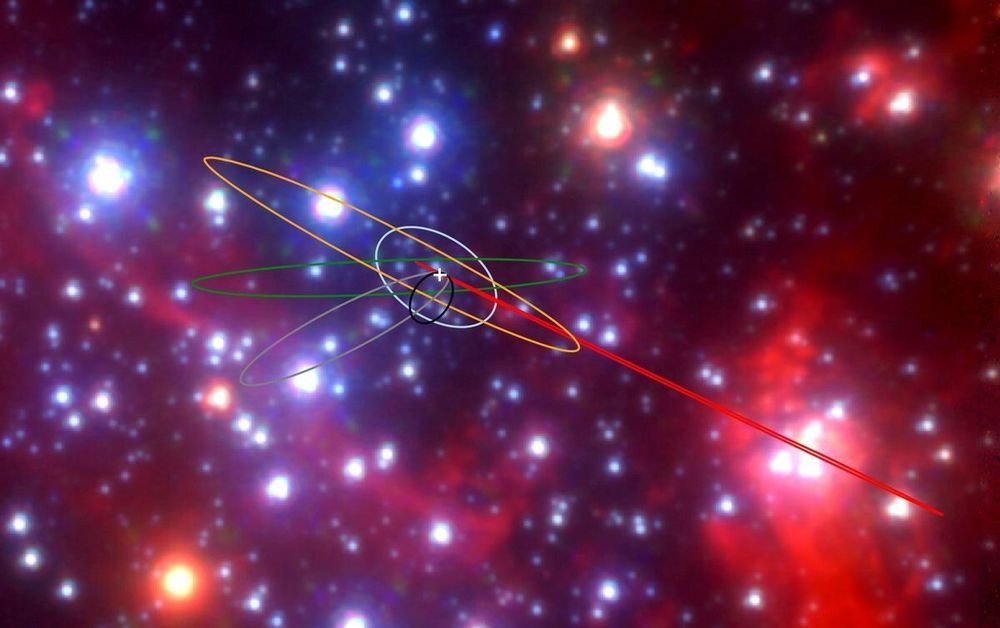

Astronomers Discover Stretchy Objects Unlike Anything Else in Our Galaxy

Astronomers have discovered a mysterious new class of objects at the heart of the Milky Way, unlike anything else found previously in our galaxy. The objects “look like gas but behave like stars,” according to senior researcher Andrea Ghez, as they start off small and compact but are stretched to a larger size when they approach the supermassive black hole in the center of the galaxy.

The researchers believe these objects could teach us about the evolution of stars and what happens to celestial bodies in environments of extreme gravity.

The puzzle began in 2005 when astronomers identified an object near the center of our galaxy called G1, which seemed to be orbiting around the supermassive black hole there in a strange way. In following years, five more objects numbered G2 to G6 were discovered. At first, these objects were thought to be clouds of gas. But one odd thing researchers noticed was that when the object G2 came very close to the event horizon of the black hole, it wasn’t torn apart in the way they would have expected. Instead, it initially stretched out, before rebounding back toward its original state.

Strange Objects Found at The Galactic Centre Are Like Nothing Else in The Milky Way

There’s something really weird in the centre of the Milky Way.

The vicinity of a supermassive black hole is a pretty weird place to start with, but astronomers have found six objects orbiting Sagittarius A that are unlike anything in the galaxy. They are so peculiar that they have been assigned a brand-new class — what astronomers are calling G objects.

The original two objects — named G1 and G2 — first caught the eye of astronomers nearly two decades ago, with their orbits and odd natures gradually pieced together over subsequent years. They seemed to be giant gas clouds 100 astronomical units across, stretching out longer when they got close to the black hole, with gas and dust emission spectra.

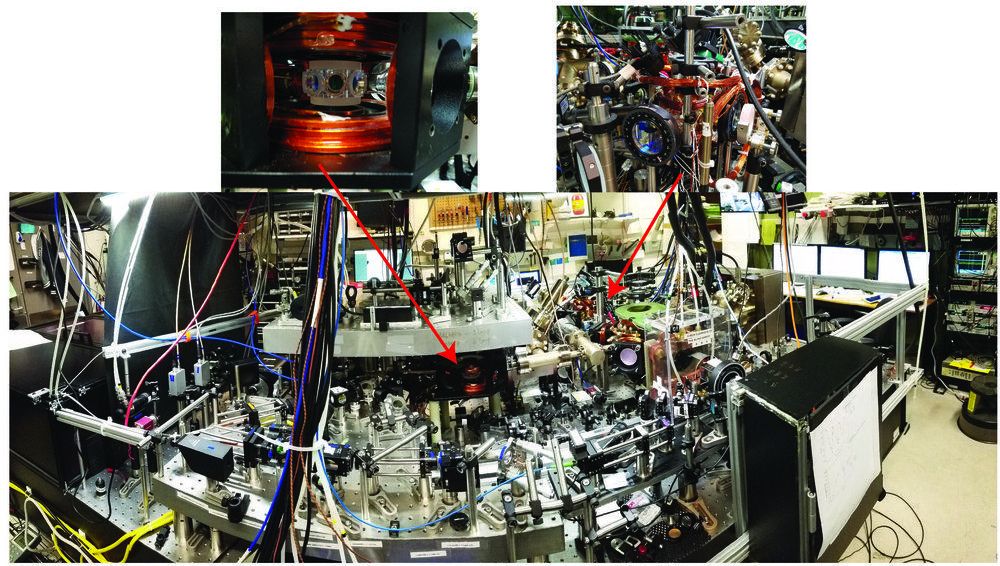

Precise measurements find a crack in universal physics

The concept of universal physics is intriguing, as it enables researchers to relate physical phenomena in a variety of systems, irrespective of their varying characteristics and complexities. Ultracold atomic systems are often perceived as ideal platforms for exploring universal physics, owing to the precise control of experimental parameters (such as the interaction strength, temperature, density, quantum states, dimensionality, and the trapping potential) that might be harder to tune in more conventional systems. In fact, ultracold atomic systems have been used to better understand a myriad of complex physical behavior, including those topics in cosmology, particle, nuclear, molecular physics, and most notably, in condensed matter physics, where the complexities of many-body quantum phenomena are more difficult to investigate using more traditional approaches.

Understanding the applicability and the robustness of universal physics is thus of great interest. Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder have carried out a study, recently featured in Physical Review Letters, aimed at testing the limits to universality in an ultracold system.

“Unlike in other physical systems, the beauty of ultracold systems is that at times we are able to scrap the importance of the periodic table and demonstrate the similar phenomenon with any chosen atomic species (be it potassium, rubidium, lithium, strontium, etc.),” Roman Chapurin, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “Universal behavior is independent of the microscopic details. Understanding the limitations of universal phenomenon is of great interest.”

Astronomers discover class of strange objects near our galaxy’s enormous black hole

Astronomers from UCLA’s Galactic Center Orbits Initiative have discovered a new class of bizarre objects at the center of our galaxy, not far from the supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A*. They published their research today in the journal Nature.

“These objects look like gas and behave like stars,” said co-author Andrea Ghez, UCLA’s Lauren B. Leichtman and Arthur E. Levine Professor of Astrophysics and director of the UCLA Galactic Center Group.

The new objects look compact most of the time and stretch out when their orbits bring them closest to the black hole. Their orbits range from about 100 to 1,000 years, said lead author Anna Ciurlo, a UCLA postdoctoral researcher.

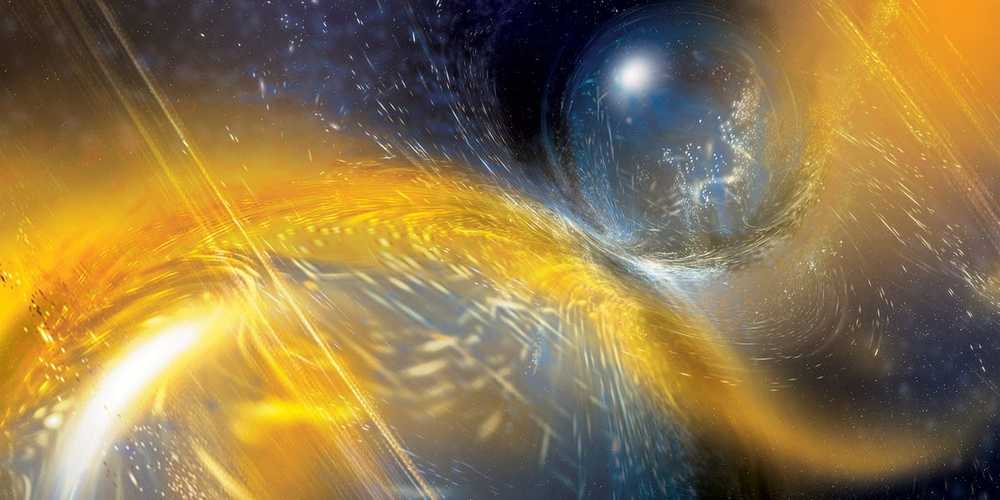

A New Study Claims to Disprove Dark Energy—but Cosmologists Aren’t Convinced

It would be really, really exciting if a single observation could completely overturn astrophysicists’ current understanding of the universe. But that hasn’t happened yet, at least with regards to dark energy.

This week, a press release proclaimed that “new evidence shows that the key assumption made in the discovery of dark energy is in error,” garnering some attention from astronomers and riling up science skeptics. But scientists have already identified some issues with the paper’s claims.