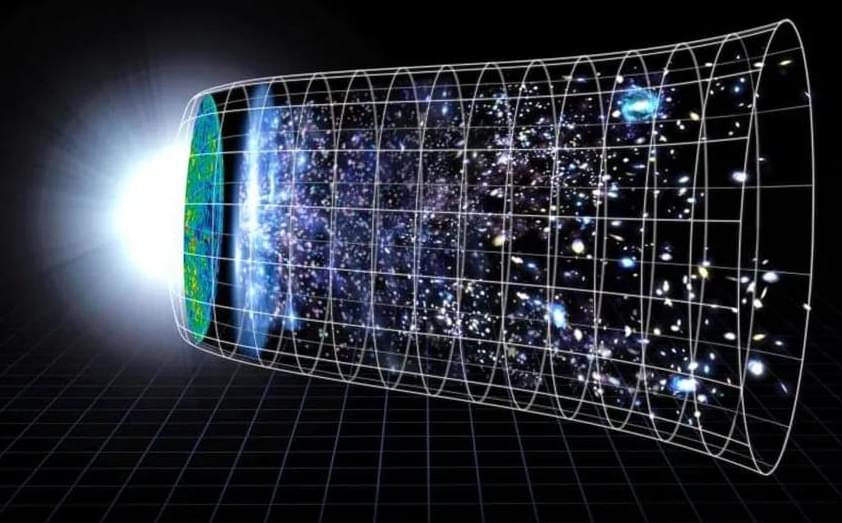

The expansion of the universe has been a well-established fact of physics for almost a century. By the turn of the millennium the rate of this expansion, referred to as the Hubble constant (H 0), had converged to a value of around 70 km s –1 Mpc –1. However, more recent measurements have given rise to a tension: whereas those derived from the cosmic microwave background (CMB) cluster around a value of 67 km s –1 Mpc –1, direct measurements using a local distance-ladder (such as those based on Cepheids) mostly prefer larger values around 73 km s –1 Mpc –1. This disagreement between early-and late-universe measurements, respectively, stands at the 4–5 σ level, thereby calling for novel measurements.

One such source of new information are large galaxy surveys, such as the one currently being performed by the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI). This Arizona-based instrument uses 5,000 individual robots that optimise the focal plane of the detector to allow it to measure 5,000 galaxies at the same time. The goal of the survey is to provide a detailed 3D map, which can be used to study the evolution of the universe by focussing on the distance between galaxies. During its first year of observation, the results of which have now been released, DESI has provided a catalogue of millions of objects.

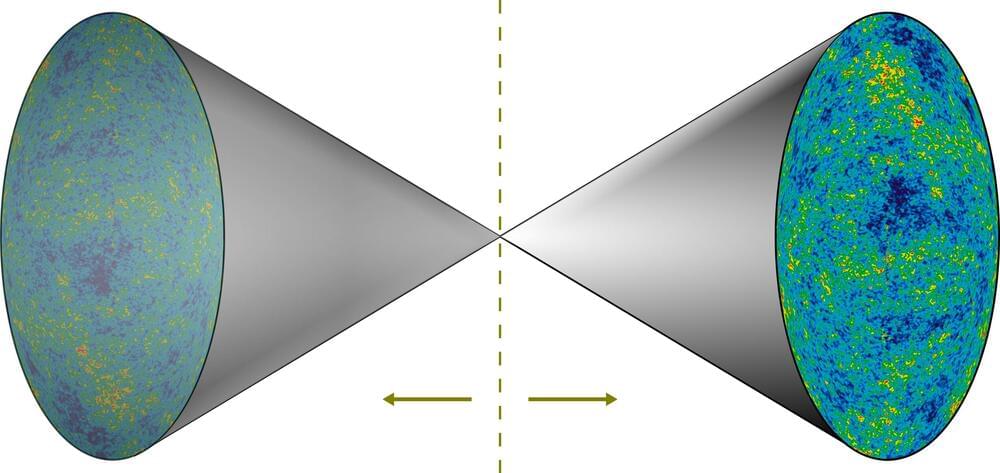

Small fluctuations in the density of the early universe resulted not only in signatures in the CMB, as measured for example by the Planck probe, but also left imprints in the distribution of baryonic matter. Each over-dense region is thought to contain dark matter, baryonic matter and photons. The gravitational force from dark matter on the baryons is countered by radiation pressure from the photons. From the small over-densities, baryons are dragged along by photon pressure until these two types of particles decoupled during the recombination era. The original location of the over-density is surrounded by a sphere of baryonic matter, which typically is at a distance referred to as the sound horizon. The sound horizon at the moment of decoupling, denoted r d, leaves an imprint that has since evolved to produce the density fluctuations in the universe that seeded large-scale structures.